Lessons Learned Along Europe’s Road to Renewables

Denmark, Portugal, and Spain have all made a rapid transition away from fossil fuels for electricity, but each in a different way

Visitors to Denmark are often taken by the ubiquitous wind turbines, which tower above the land and sea. On one windy day in December 2013, these turbines provided more electricity than the entire nation could use—a first for Denmark or any country.

While that day was exceptional, wind met 39 percent of Denmark’s electricity needs last year, the highest share of any nation. And wind isn’t Denmark’s only renewable energy source; the country has also been investing heavily in biomass power plants that burn woody material and straw and in biogas tanks that capture methane from organic material to produce electricity. Add in solar arrays and renewable sources accounted for 60 percent of Denmark’s electricity in 2014, according to Energinet, the company that operates the Danish electricity and gas grids.

Of course, Denmark is not alone in its drive to harness more renewable energy. Portugal last year met 30 percent of its electricity demand with nonhydropower renewables, and Spain reached 27 percent. Together, these three nations are leading Europe’s clean energy revolution. (Germany, meanwhile, has also invested heavily in solar and wind power, but the share of electricity it gets from renewable sources lags that of Denmark, Portugal, and Spain; see “Has Germany’s Energy Transition Stalled?”)

These three countries overcame the technical challenges of integrating intermittent solar and wind sources into their grids; additionally, Spain and Portugal have improved the overall reliability of their power systems, while Denmark has maintained a highly reliable grid. Considered together, the three countries show that no special geography is required for switching to renewables. The fact that solar and wind technologies have become much cheaper and more efficient in recent years did not play a significant role (although it didn’t hurt). Instead, in all three cases, a deliberate energy policy has been the key driver.

Denmark: The pioneer

Europe’s energy transition began in Denmark, which embraced wind power and other renewable sources decades before any scientific consensus on man-made climate change emerged. What motivated the Danes was the country’s overdependence on fossil fuels.

In 1973 and again in 1979, skyrocketing oil prices hit many countries around the world. Denmark, where imported petroleum met 90 percent of energy needs, was particularly pained. The Danish government at first considered building nuclear power plants, but this idea proved unpopular. Paul Gipe, the author of more than a dozen books on wind and renewable energy policy, has studied the Danish experience extensively. He says members of Denmark’s antinuclear movement began building small, locally owned wind turbines as an alternative.

“There was a citizens’ movement to develop wind energy, and it got ahead of the government,” says Gipe. “The citizens’ movement said if the government is not going to take action in developing wind energy, we will take control in our hands. We will build the turbines and connect them to the grid.”

Federal policies responded to this development in various ways. In 1985, for instance, the Danish government began a program to subsidize 30 percent of the cost of installing wind turbines and other renewable energy sources; later it required that utilities purchase this electricity at an agreed price, with a bonus from its carbon tax.

These policies in turn gave rise to Denmark’s wind industry, led by homegrown manufacturers such as Vestas Wind Systems, Nordtank Energy Group (which later merged with NEG Micon and then Vestas), and Bonus Energy (which was acquired by Siemens). Danish wind turbines became progressively larger and more sophisticated and were deployed widely throughout the nation.

“Other countries had support for research and development and universities,” says Birger T. Madsen, who was chair of the Danish Wind Industry Association in the 1980s. “Denmark was the only nation to have direct market stimulation. It took 10 years before all the other European countries caught up with that model.”

Another turning point came in 1993, with the establishment of what’s known as a standard offer policy. This nationwide policy increased the payment levels to wind projects and provided support equally across the nation. As a result, Danish wind capacity grew sixfold, to 3.1 gigawatts, over the next 10 years.

Of course, wind is the most variable electricity source, and its output is hard to forecast. In any electricity system, supply and demand must be balanced, and this is harder to do when the electricity supply is continuously changing and you have limited visibility as to how much power will be available. Reliably integrating large amounts of wind generation into the grid thus presented a technical challenge. Grid interconnections with neighboring countries proved vital because they allowed Denmark to send excess power abroad on windy days and to import power in times of low wind—a much less expensive solution than available forms of energy storage. Indeed, the nation has one of the highest degrees of regional interconnection in the world, with a series of high-voltage power lines running under the icy waterways that separate it from Sweden and Norway, as well as overland transmission to Germany. Through Scandinavia's regional power market, Denmark trades electricity with Finland, Norway, and Sweden in intervals of less than an hour.

Danish grid operators were skeptical at first about their ability to export and import so much power so quickly, but they soon realized it was feasible. In 2003, for instance, the chairman of Western Denmark’s grid operator noted that although the company had feared its system could not handle wind capacity above 500 megawatts, it was by then handling nearly five times as much.

As a result, even though renewables now provide 60 percent of Denmark’s electrical generation, its grid is markedly more reliable than that of the United States. On average, the United States has three times as many outages as Denmark, with each outage lasting 14 times as long.

To be sure, Denmark’s transition toward renewable energy has not been entirely smooth. In 2001, a center-right government took office; it changed the incentive structure for wind and removed the right of turbine operators to interconnect to the grid. By 2004, the building of new wind farms had ground to a halt, and very little new capacity was added over the next four years.

In 2008, in anticipation of the Copenhagen Climate Change Conference the following year, the same government began promoting large-scale wind deployments once again. The leftist coalition government that took power in 2011 has taken renewables even further, calling for 100 percent renewable energy in the electricity and heating sectors by 2035.

Spain: The roller coaster

Spain was the next European nation to broadly embrace renewable energy. Like Denmark, it suffered in the 1970s due to its heavy dependence on imported petroleum. It did not immediately turn to renewables as an alternative, however. And in general, Spain has experienced far more ups and downs in its transition away from fossil fuels.

Spain’s wind movement began in the northern region of Navarre, where in 1997, Spanish wind turbine maker Gamesa Corporación Tecnológica, Denmark’s Vestas, and the regional government undertook a wind project of unprecedented size. Backed by the European Investment Bank, which handles loans for the European Union, the Guerinda project initially comprised 115 turbines totaling 69 MW—the largest in Europe at the time and the first of a series of even larger projects.

That same year, Spain implemented its version of a standard offer policy. The policy required that utilities purchase electricity generated by renewables and offered a premium for this power. Power companies such as Acciona, Endesa, and Iberdrola saw an opportunity to start building their own wind farms. “Endesa was manufacturing its own turbines and looking for places to put them,” notes journalist Michael McGovern, who lives in Spain and has written extensively about its wind industry.

Spain’s standard offer policy led to a 39-fold increase in wind capacity over the next dozen years, to 16.7 GW by 2008—far more than was deployed even in Denmark. For a time Spain was the center of the global wind industry and the largest market.

As in Denmark, Spanish grid operators doubted that they could integrate so much wind, in large part because Spain had very limited grid interconnections with its neighbors France and Morocco; its ability to trade electricity with Portugal was greater, but Portugal is a much smaller market. (In February Spain completed a high-voltage line to France that doubled its interconnection capacity with that country.)

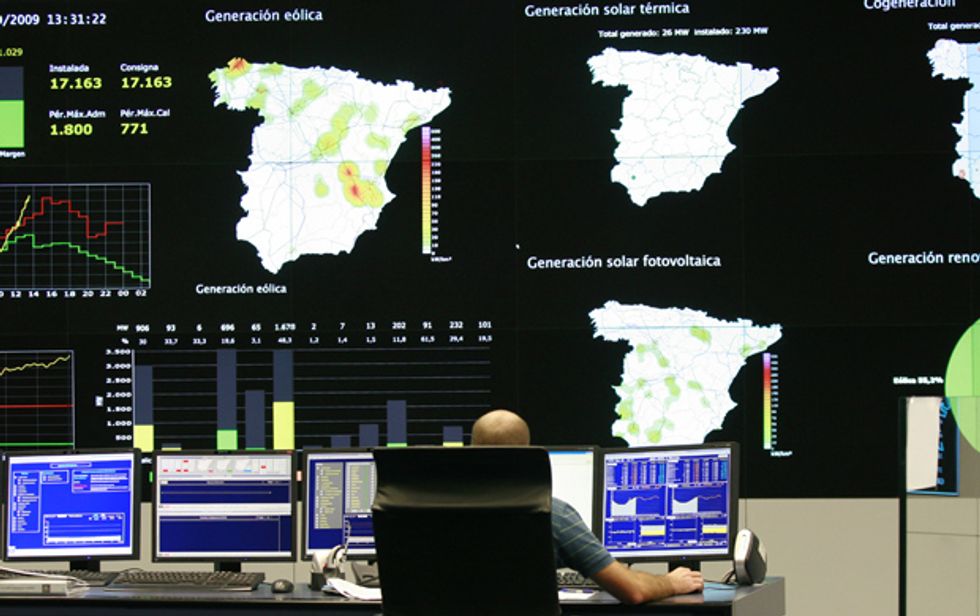

As a solution, grid operator Red Elétrica de España (REE) built a centralized dispatch system and required that all wind farms operate under its control starting in 2006. According to McGovern, this was the first such system in the world, and it enabled the integration of large amounts of wind, from a negligible amount in 1995 to 20 percent of annual demand in 2014. McGovern recalls that prior to creating the centralized system, REE had insisted that wind could not provide a maximum output equal to more than 12 percent of national electricity demand; these days, he notes, wind generation in Spain reaches a peak of more than 60 percent.

Spain also invested heavily in solar photovoltaics, experiencing a solar boom in 2007 and 2008. New deployments were helped by a generous feed-in tariff that set electricity rates for renewable energy generators above their calculated costs. In 2008 alone, Spain installed more than 2.5 GW of PV, which at the time was nearly half of the global market. In addition, the feed-in tariff supported the construction of nearly 2 GW worth of large solar thermal electric plants.

Such huge deployments resulted in higher than expected costs to the electricity system, in large part because solar was much more expensive per unit of power delivered than was on-shore wind. An existing law that set limits on retail electricity rate increases further complicated matters; it required that the government pay for any shortfalls between a utility’s revenues and its costs. This rate freeze led in 2009 to the Spanish electricity system running a deficit of 4 billion euros [pdf]—roughly 20 percent above its revenues.

This “tariff deficit” came at the worst possible time, as Spain was hit hard by the global recession beginning in 2008. The center-left government responded by introducing a series of retroactive reductions to feed-in tariff rates. When the center-right Popular Party came to power in 2012, it took even more drastic measures. Starting in January 2012, it froze all renewable energy incentives and a year later retroactively replaced the feed-in tariffs with an extremely complicated system that paid renewable energy producers far less.

These cuts halted renewable energy investments in Spain, and they now threaten to bankrupt tens of thousands of people who invested in wind and solar. This collapse in renewable energy deployment is particularly tragic given Spain’s past leadership in wind and solar thermal technologies and its success in integrating large volumes of renewables in a geographically constrained system.

Portugal: The forgotten leader

Few people outside of Portugal know about its renewable energy transition, and yet it has also been a leader. In 2014, renewable sources supplied 63 percent of the country’s electricity, according to Portugal’s Renewable Energy Association (APREN).

Well into the 1990s, Portugal imported fossil fuels for a majority of its electricity generation, until, like Denmark and Spain, it finally turned to renewables. However, unlike the other two countries, Portugal was less subject to oil-related price shocks because it gets a large portion of its electricity from hydroelectric dams, with a total capacity of 5.7 GW. Portugal’s experience shows that even countries with substantial hydroelectric capacity can still benefit from deploying large amounts of nonhydro renewables.

In 1995, Portugal introduced a standard offer policy for renewables, two years after Denmark and two years before Spain. The policy has gone through multiple iterations since then; after the formula was changed in 2001, the nation’s wind market grew 20-fold, to 4.1 GW, over the next decade. Additionally, Portugal has deployed 722 MW of biomass and biogas, including waste incineration, and 414 MW of solar PV.

As happened in Spain, the Portuguese electricity system became more reliable even as the share of wind generation grew. Likewise, the standard offer enabled utilities to participate in renewable energy production. The Portuguese utility Energias de Portugal, for instance, became a global wind and solar developer, with projects across Europe and North America and in Brazil. Additionally, electricity prices fell.

But in 2011, Portugal’s energy transition fell victim to the global financial crisis. As a condition of Portugal’s postrecession bailout, the International Monetary Fund and foreign lenders forced the nation to reduce or revoke several of its incentives for renewable energy. Independent power producers are also facing difficulties in connecting to the grid, owing to the grid’s low capacity. However, some large projects are now moving forward; most notably, a consortium of Portuguese companies and Germany’s Ferrostaal are building five large wind farms totaling 172 MW.

To the future

While Portugal, Spain, and Denmark have been leaders in the transition to renewables, they are not alone; most Western European countries are heading in that direction. A recent study by the International Energy Agency [pdf] shows that many countries can get up to 45 percent of their electricity from wind and solar without substantially increasing system costs, provided that installations are appropriately integrated into the grid, investments are made in flexible generation, and energy market rules are reformed.

At higher penetrations, energy storage may be necessary to balance fluctuations in supply and demand. Spain and Italy are currently deploying large-scale storage, whereas Germany has created incentives for homeowners to add batteries to their residential PV systems. If the past is any indication, the technical issues with energy storage will eventually be sorted out.

Far trickier will be the politics. The rapid deployment of large volumes of renewables requires both political will and a consistent policy. Yet, as noted above, even in those countries that have led the renewable energy transition, such support has not been consistent. In Western Europe, new governments, particularly conservative ones, have tended to undermine any strong renewable energy policies passed by previous governments.

Worldwide, the nations that have had the greatest success with renewable energy have introduced some form of standard offer policy, and dozens of countries now have them. In 2013, following the passage of feed-in tariffs, China and Japan deployed the largest volume of solar PVs in the world, and they continued to do so in 2014.

A number of studies have suggested how countries could eventually meet 100 percent of their electricity needs with renewables. What the experiences of Denmark, Portugal, and Spain show is that meeting a substantial portion of electricity demand with renewable energy is feasible now and does not depend upon a special geography, an existing set of circumstances, or widespread deployment of energy storage. What is needed is political will, effective policies, and a commitment to structuring the electricity system to support renewable energy. Whether other countries follow this lead is their choice to make.

About the Authors

Christian Roselund (@croselund) is the global content director for SolarPV TV. He previously covered the global solar industry for the trade publications pv magazine and SolarServer. John Bernhardt (@bernzzi) is the outreach and communications director for the Clean Coalition.

To Probe Further

Comparisons of 12 countries’ experience with wind power can be found in 30 Years of Policies for Wind Energy [pdf], a 2012 report from the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA).

Country-by-country comparisons of renewable energy in the European Union can be found in The State of Renewable Energies in Europe [pdf], 2014 edition.

For a breakdown of Portugal’s renewable energy sector, see the report (in Portuguese) Renewables—Quick Statistics, December 2014 [pdf] by Portugal’s General Directorate for Energy and Geology.

Paul Gipe’s website, Wind-works.org, has information about feed-in tariffs for renewable energy around the world.