Germany Folds on Nuclear Power

Berlin’s decision to shut down reactors means tough energy choices ahead

Editor’s Note: This is part of the IEEE Spectrum special report: Fukushima and the Future of Nuclear Power.

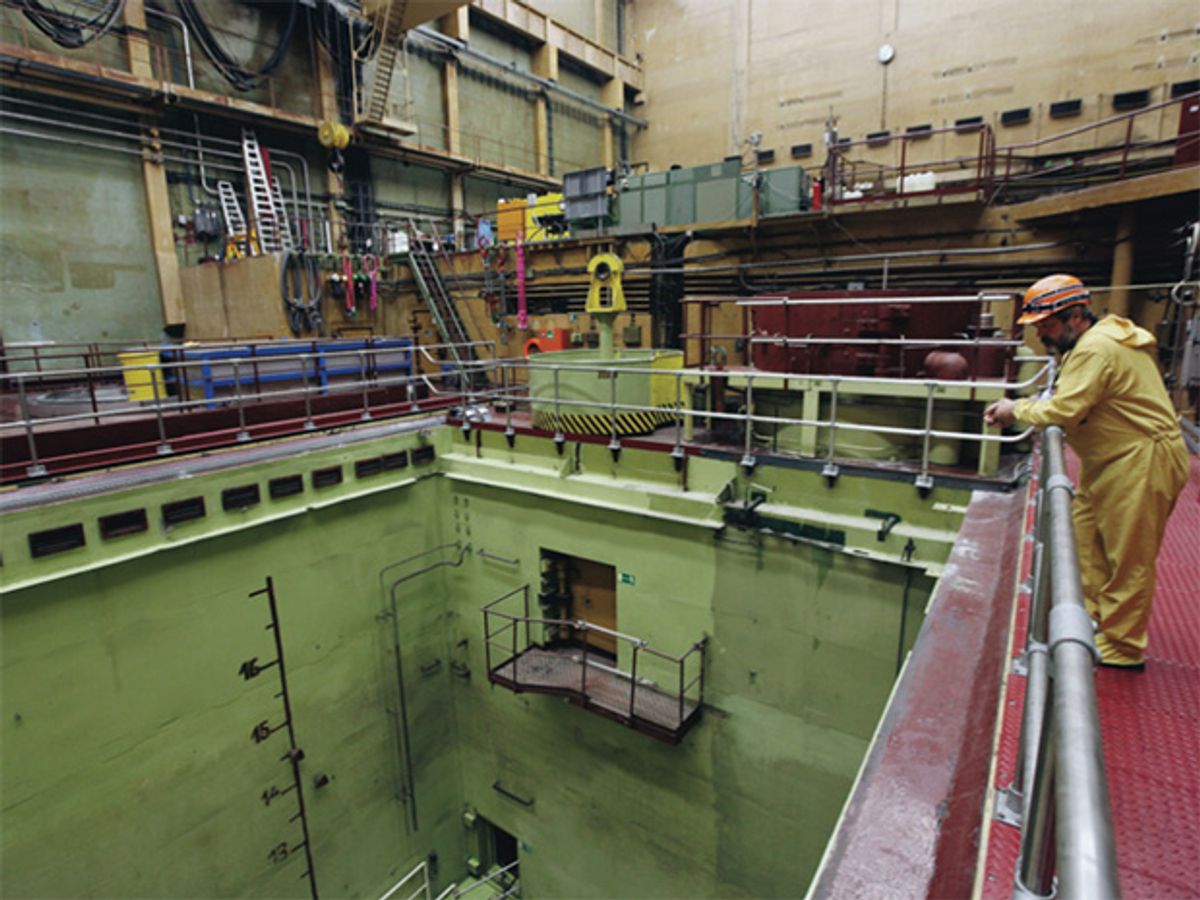

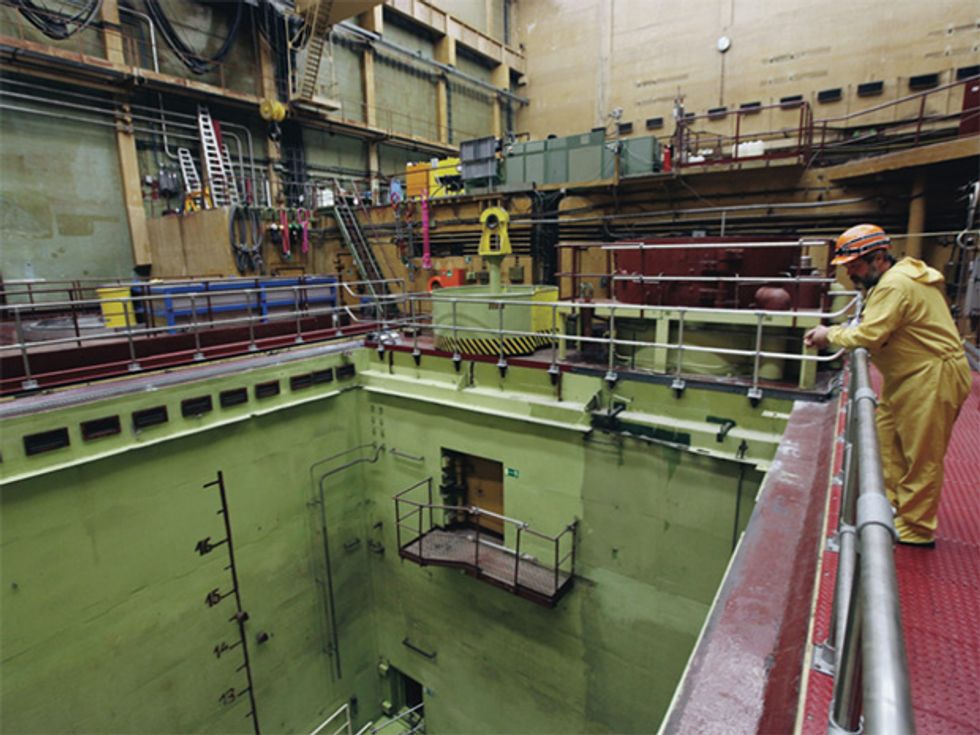

Among major industrialized nations, Germany has long stood out for its deep ambivalence about nuclear power. So it wasn’t much of a surprise when, two months after the Fukushima crisis began, Environment Minister Norbert Rottgen announced that Germany would shut down all its nuclear plants by 2022. And the phaseout began immediately: Rottgen declared that eight of the country’s oldest reactors, seven of which had been idled after Fukushima, would never go online again.

So what now? Germany’s 17 reactors had provided 28 percent of its power. To make up for the energy shortfall, officials named some of the usual suspects: offshore wind farms, coal-fired power plants fitted with carbon sequestration technology, and additional transmission lines to accommodate added renewable generation. But all of those options have provoked intense opposition in Germany. The upshot is that many analysts expect Germany’s nuclear shutdown to collide headlong with its long-standing goal to cut greenhouse gases.

Germany has pledged to slash its carbon emissions by 2020, to 40 percent below 1990 levels. But Claudia Kemfert, head of the energy, transportation, and environment department at the German Institute for Economic Research, says the country will probably fail to reach that goal. “It’s easy to say we’ll phase out nuclear power,” Kemfert says. The difficult part will be doing so without resorting to greater dependence on fossil fuels, such as lignite and hard coal, which currently account for 40 percent of power production. That, she says, will require a fundamental restructuring of the nation’s energy infrastructure. “The question is how to change the whole electricity system,” she explains.

Lawmakers have already started the transition. The law that finalized the nuclear phaseout includes provisions that support the expansion of renewable generation to meet at least 35 percent of the country’s power consumption by 2020—more than double its share in 2010. Parliament also approved laws to accelerate grid upgrades and allow carbon sequestration.

Germany is already a world leader in the installation of solar panels and wind turbines, thanks to its existing energy policies. But to reach the new 2020 target for renewable generation, the country must solve problems that have bedeviled it in the past. Offshore wind farms proposed over the last decade have run into stiff resistance from wildlife conservationists; that opposition has pushed the development zone farther out to sea and driven up costs. Germany’s first commercial-scale offshore wind project, the 400-megawatt Bard 1, will stand some 112 kilometers from shore. By the project’s completion in 2012, construction costs are expected to total 1.9 billion (US $2.6 billion)—40 percent more per megawatt than offshore wind farms in the United Kingdom.

The new transmission-planning law, meanwhile, is intended to deliver the 3600 km of added high-voltage lines that grid operators need to integrate new power from anticipated renewable installations. Legislators hope that by streamlining the approvals process and compensating affected communities, the law can resolve persistent conflicts and thus cut four to six years off the 10 currently required to build new lines.

Most energy analysts agree that Germany will also need new fossil-fueled power plants to meet its energy demands, if only to replace aging and inefficient coal-fired stations. Kemfert predicts many of these will be fueled by natural gas, because German policymakers have lost patience with coal’s heavy carbon footprint and they aren’t sold on carbon sequestration as a large-scale solution. (The July 2011 law authorizing sequestration gave German states veto power over local projects, and Kemfert has no doubt they will use it.)

Though natural gas supplied just 14 percent of Germany’s electric power last year and delivers costlier power than coal, Kemfert believes it’s a good fit for the country. Gas-fired plants currently produce one-half to one-third the greenhouse-gas emissions of coal plants and could even become renewable generators, thanks to Germany’s increasing production of biogas from animal waste.

However, all these solutions will take time to implement, and Germany will need energy to keep the lights on in the meantime. One possible, ironic source of that energy: nuclear power imported from France and the Czech Republic.

This article originally appeared in print as “Germany Folds.”

About the Author

Peter Fairley writes about energy as a contributing editor for IEEE Spectrum. Fairley, a world traveler who divides his time between Vancouver Island and Paris, has the international perspective Spectrum needed for articles about China’s nuclear-powered future and Germany’s nuclear-free future. “When it comes to energy, every country has its own unique set of political restraints and cultural hang-ups,” he says. “That’s what makes it interesting.”