A Software Shrink: Apps and Wearables Could Usher In an Era of Digital Psychiatry

Data is about to revolutionize the treatment of depression, schizophrenia, and many other disorders

Zach has been having trouble at work, and when he comes home he’s exhausted, yet he struggles to sleep. Everything seems difficult, even walking—he feels like he’s made of lead. He knows something is wrong and probably should call the doctor, but that just seems like too much trouble. Maybe next week.

Meanwhile, software on his phone has detected changes in Zach, including subtle differences in the language he uses, decreased activity levels, worsening sleep, and cutbacks in social activities. Unlike Zach, the software acts quickly, pushing him to answer a customized set of questions. Since he doesn’t have to get out of bed to do so, he doesn’t mind.

Zach’s symptoms and responses suggest that he may be clinically depressed. The app offers to set up a video call with a psychiatrist, who confirms the diagnosis. Based on her expertise, Zach’s answers to the survey questions, and sensor data that suggests an unusual type of depression, the psychiatrist devises a treatment plan that includes medication, video therapy sessions, exercise, and regular check-ins with her. The app continues to monitor Zach’s behavior and helps keep his treatment on track by guiding him through exercise routines, noting whether or not he’s taking his medication, and reminding him about upcoming appointments.

While Zach isn’t a real person, everything mentioned in this scenario is feasible today and will likely become increasingly routine around the world in only a few years’ time. My prediction may come as a surprise to many in the health-care profession, for over the years there have been claims that mental health patients wouldn’t want to use technology to treat their conditions, unlike, say, those with asthma or heart disease. Some have also insisted that to be effective, all assessment and treatment must be done face to face, and that technology might frighten patients or worsen their paranoia.

However, recent research results from a number of prestigious institutions, including Harvard, the National Alliance on Mental Illness, King’s College London, and the Black Dog Institute, in Australia, refute these claims. Studies show that psychiatric patients, even those with severe illnesses like schizophrenia, can successfully manage their conditions with smartphones, computers, and wearable sensors. And these tools are just the beginning. Within a few years, a new generation of technologies promises to revolutionize the practice of psychiatry.

To understand the potential of digital psychiatry, consider how someone with depression is usually treated today.

Depression can begin so subtly that up to two-thirds of those who have it don’t even realize they’re depressed. And even if they realize something’s wrong, those who are physically disabled, elderly, living in rural areas, or suffering from additional mental illnesses like anxiety disorders may find it difficult to get to a doctor’s office.

Once a patient does see a psychiatrist or therapist, much of the initial visit will be spent reviewing the patient’s symptoms, such as sleep patterns, energy levels, appetite, and ability to focus. That too can be difficult; depression, like many other psychiatric illnesses, affects a person’s ability to think and remember.

The patient will likely leave with some handouts about exercise and a prescription for medication. There’s a fair chance that the medication won’t be effective at least for many weeks, the exercise plan will be ignored, and the patient will have a bumpy course of progress. Unfortunately, the psychiatrist won’t know until a follow-up appointment sometime later.

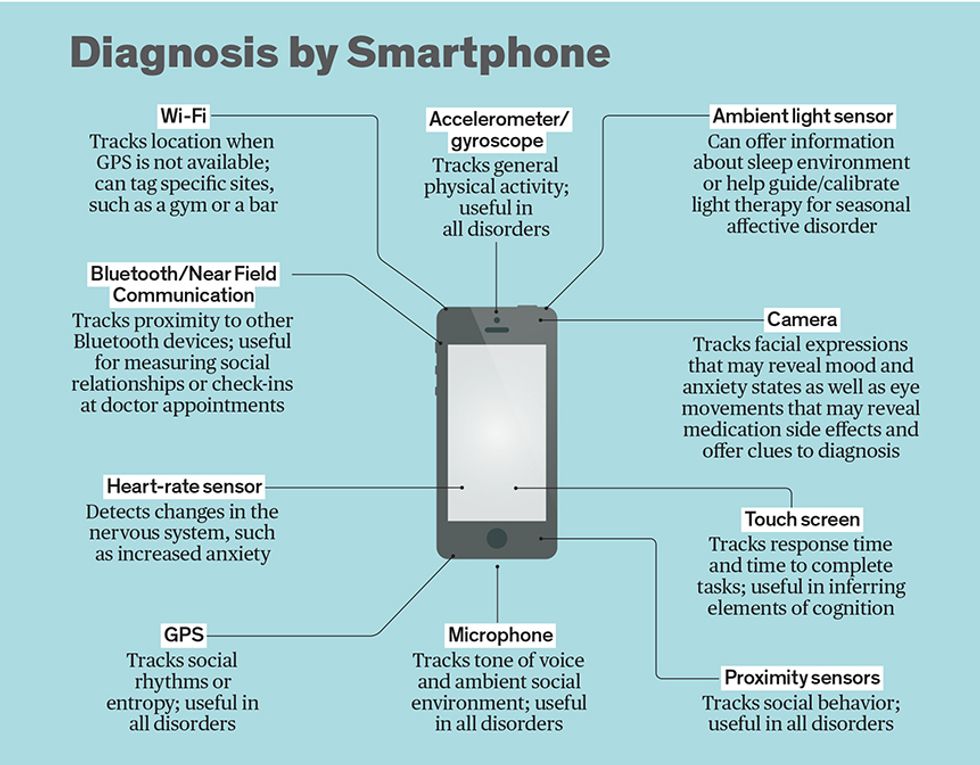

Technology can improve this outcome, by bringing objective information into the psychiatrist’s office and allowing real-time monitoring and intervention outside the office. Instead of relying on just the patient’s recollection of his symptoms, the doctor can look at behavioral data from the person’s smartphone and wearable sensors. The psychiatrist may even recommend that the patient start using such tools before the first visit.

It’s astonishing how much useful information a doctor can glean from data that may seem to have little to do with a person’s mental condition. GPS data from a smartphone, for example, can reveal the person’s movements, which in turn reflects the person’s mental health. By correlating patients’ smartphone-derived GPS measurements with their symptoms of depression, a 2016 study by the Center for Behavioral Intervention Technologies at Northwestern University, in Chicago, found that when people are depressed they tend to stay at home more than when they’re feeling well. Similarly, someone entering a manic episode of bipolar disorder may be more active and on the move. The Monitoring, Treatment, and Prediction of Bipolar Disorder Episodes (Monarca) consortium, a partnership of European universities, has conducted numerous studies demonstrating that this kind of data can be used to predict the course of bipolar disorder.

Where GPS is unavailable, Bluetooth and Wi-Fi can fill in. Research by Dror Ben-Zeev, of the University of Washington, in Seattle, demonstrated that Bluetooth radios on smartphones can be used to monitor the locations of people with schizophrenia within a hospital. Data collected through Wi-Fi networks could likewise reveal whether a patient who’s addicted to alcohol is avoiding bars and attending support-group meetings.

Accelerometer data from a smartphone or fitness tracker can provide more fine-grained details about a person’s movements, detect tremors that may be drug side effects, and capture exercise patterns. A test of an app called CrossCheck recently demonstrated how this kind of data, in combination with other information collected by a phone, can contribute to symptom prediction in schizophrenia by providing clues on sleep and activity patterns. A report in the American Journal of Psychiatry by Ipsit Vahia and Daniel Sewell describes how they were able to treat a patient with an especially challenging case of depression using accelerometer data. The patient had reported that he was physically active and spending little time in bed, but data from his fitness tracker showed that his recollection was faulty; the doctors thus correctly diagnosed his condition as depression rather than, say, a sleep disorder.

Tracking the frequency of phone calls and text messages can suggest how social a person is and indicate any mental change. When one of Monarca’s research groups [PDF] looked at logs of incoming and outgoing text messages and phone calls, they concluded that changes in these logs could be useful for tracking depression as well as mania in bipolar disorder.

Combining all these data streams will amplify the power of digital psychiatry. Today, studies are under way using apps and sensors to explore nearly every subtype of mental illness. I am part of a collaboration between Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center’s Digital Psychiatry Program and the Onnela Lab at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, both in Boston, that is studying how the various types of sensor data described above can help predict relapses in schizophrenia, as well as better understand what patients with schizophrenia experience when they relapse.

It’s not just behavioral data that is valuable. Physiological data such as heart rate, temperature, and galvanic skin response can also shed light on a person’s mental well-being. Such data is already collected by some wearable devices. Numerous studies have shown that heart rate variability can be used to track the severity of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Galvanic skin response, a measurement of the electrical conductance of the skin that varies with the state of sweat glands and is controlled by the “fight or flight” component of the nervous system, can offer clues into the biological activity that may be overactive in anxiety disorders.

Ultimately, psychiatric disorders are brain disorders, and using electroencephalography (EEG) to monitor brain activity has long been an accepted practice in psychiatric research and biofeedback treatments. Newer, consumer-grade EEG gadgets are now on the market, but it’s still unclear how effective they are. In time, though, as the technology improves and expands—3D-printed EEG headsets and less cumbersome electrodes may be promising—these devices will likely prove more useful.

Beyond just diagnosing and monitoring mental illness, digital psychiatry can also help treat certain conditions. Without knowing whether or not a patient is taking his medication, for example, a doctor can’t identify the cause of any continued problems. It could be that the drug isn’t effective, or the patient isn’t taking the medication as prescribed.

Sensors embedded in pills can help. In the case of aripiprazole, an antipsychotic drug, researchers added an ingestible sensor that detects stomach acid and then sends a signal to a wearable patch to confirm that the medication has been taken. The patch, in turn, forwards the information via Bluetooth to a smartphone. This intervention proved both technically feasible and acceptable to patients with schizophrenia. For such patients, systems backed by artificial intelligence, simulations run in virtual reality, and even cheaper and simpler solutions, like those based on text messaging, may likewise help patients adhere to medication schedules.

Many psychiatric treatments aren’t medications, of course. Studies show that therapy sessions can also benefit from a digital psychiatry approach. Today, therapy requires visiting an office, but it can be just as effective to conduct the session via computer or smartphone, and it’s more convenient for the average patient. Computers and smartphones can even deliver specialized therapy involving virtual reality technology. Doctors now use VR therapy, in the office or at home, to help patients overcome phobias, such as a fear of heights or spiders, as well as to help soldiers suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. And a pilot study at the University of Oxford, in England, recently demonstrated that VR tools may reduce the delusional beliefs that come with schizophrenia, while researchers at Stanford University are exploring augmented reality glasses to help children with autism.

The ultimate promise of digital psychiatry is that it could help improve everyone’s mental health. It shouldn’t be too difficult to use the Internet of Things to encourage healthy behaviors—for instance, automatically dimming the lights in the home at a recommended bedtime or turning off the TV to encourage exercise. Relaxing music could be cued to ease stress, and window shades could be programmed to let in the maximum amount of natural light.

To be sure, there is much that digital psychiatry’s tools cannot yet do or that researchers have not yet proven they can do. Any new health-care technology must be validated clinically before it can become mainstream. While many of the tools discussed already exist, few have been well studied for use in psychiatric disease.

Taking therapies that work well when delivered in person and translating them into digital or mobile versions isn’t always straightforward. For example, one study looked at an app designed to help people quit smoking; it was based on an effective in-person smoking-cessation treatment. But the study found that only some elements of the therapy were successful in app form. What’s more, the app features that users liked most, like tracking how often they smoked or sharing progress with friends, weren’t actually the most effective at changing behavior, while more effective techniques, like practicing resistance to an urge to smoke until it passes, were less popular on the app.

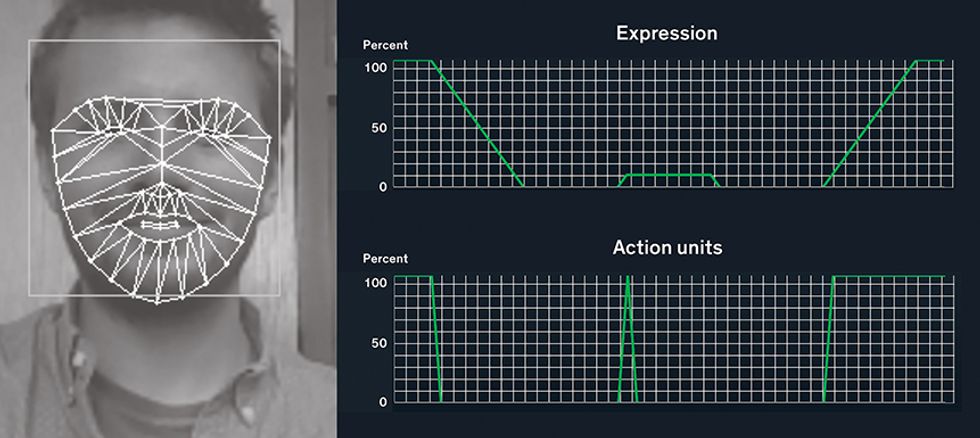

Plenty of technical challenges also remain. On the diagnostic side, the biggest one is emotion sensing. We can now capture a tremendous amount of behavioral and physiological data on the go and in real time, but we don’t fully understand how to connect this information with how someone is feeling. Many companies have proposed various big-data analytical methods to synthesize sensor data in order to draw conclusions about mental health, but transforming these promising ideas into scalable and reproducible results that give doctors and patients useful information remains a challenge.

A different kind of challenge is patient adherence to technology-driven programs. Many researchers and clinicians worry that patients will stop using their apps or wearing their sensors once the novelty wears off. Mental illnesses tend to be chronic, and nearly all require treatment or monitoring for at least several months, so a technology that gets abandoned after a few weeks won’t be too helpful.

But assuming we can get patients to use their digital psychiatry tools, we still have to address the basic issues of battery life and data security. Constantly running the GPS on a phone, for example to monitor a patient’s location, quickly depletes the battery. Until longer-lived smartphone batteries come along, it will remain impractical to collect huge amounts of behavioral data that way. Researchers also worry about security flaws in specific apps as well as in data transmission and storage, which could reveal confidential patient data to others. Given the stigma associated with mental illness, security has to be a top concern for anyone thinking of developing or using digital psychiatry tools. Ethical concerns about how apps respect privacy and use patient data remain rife, with many mental health apps still lacking even basic privacy policies or covertly selling users’ mental health information to data brokers. Efforts like the Connected and Open Research Ethics project are trying to bring more trust and transparency to the field and to advocate for patients and consumers.

Despite these challenges, the digital future of psychiatry may be much closer than we realize. The smartphone-based treatment scenario described at the start of this article is already within sight, and all of the individual elements exist today. Meanwhile, various groups are working on algorithms to extract meaningful information from the sea of behavioral data generated by phones and sensors. And in general, mental health apps are becoming more usable and engaging; some, like the smoking-cessation app, even have social or game features.

I predict that this technology will have an enormous impact on psychiatry. It cannot happen soon enough. One in five people around the world will suffer from a psychiatric illness over the course of a lifetime, but far fewer will seek or receive professional help. According to the World Health Organization, this year depression moved past hearing loss and vision problems to become the leading cause of ill health and disability worldwide.

But the technology to help those with psychiatric illnesses can reverse this trend. Such technology can be modified, scaled, and culturally adapted to serve the global population—but only if we, members of the engineering and mental health professions, work together to make that happen.

This article appears in the July 2017 print issue as “The Case for Digital Psychiatry.”

About the Author

John Torous is a psychiatrist and codirector of the digital psychiatry program at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.