Virtual Reality Is Addictive and Unhealthy

Interactive technologies give us a quick fix, and that’s not a good thing

In my days as an engineer, I ran the microprocessor division at Intel Corp. I then became a venture capitalist, investing in companies that built semiconductors, computers, networking systems, and Internet-related services. I focused on products that helped businesses run more effectively and gave little thought to how they might affect our minds, social interactions, and governance.

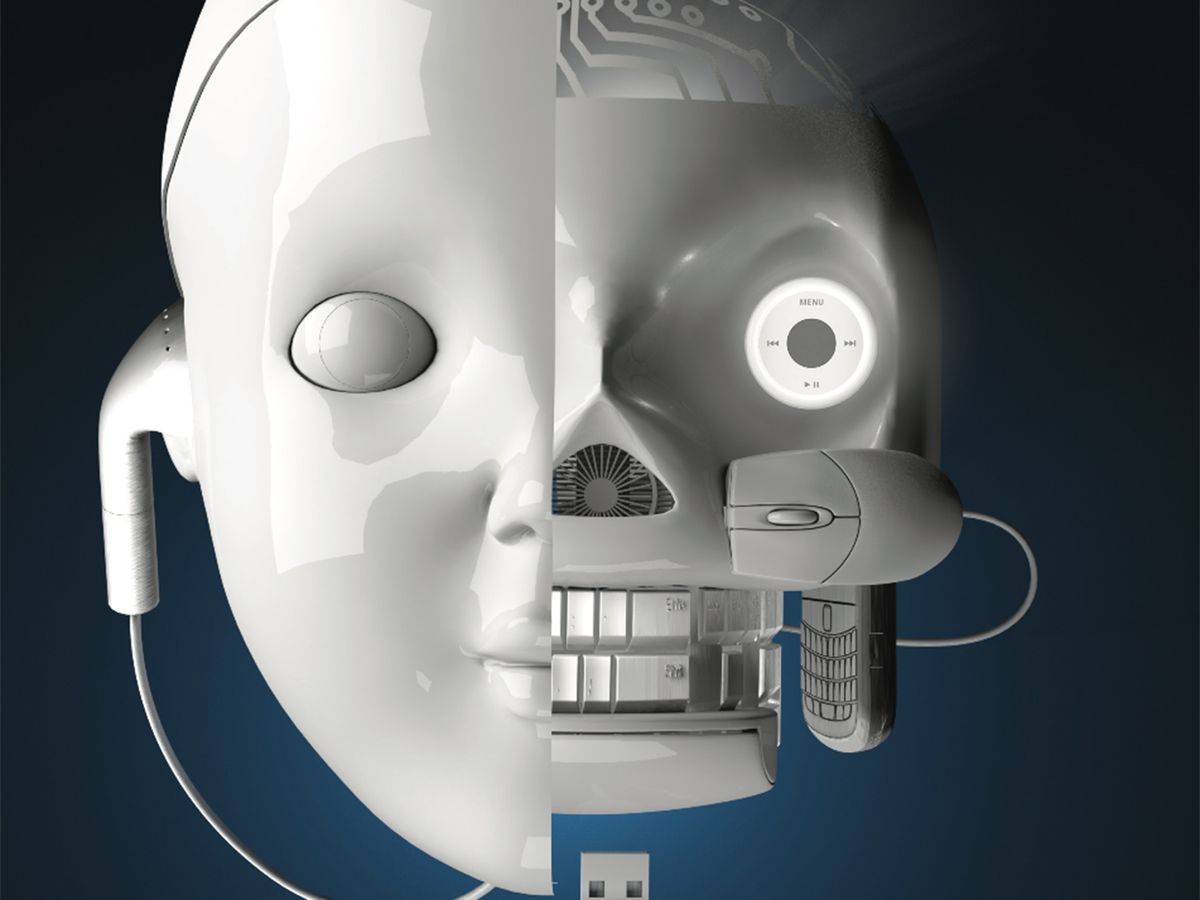

That lapse now comes home to me as I see people walking down the street, eyes fixed on the screens of their mobile phones, ears plugged into their iPods, oblivious to their surroundings…to reality itself. They are not managing their tools; their tools are managing them. Tools now make the rules, and we struggle to keep up.

I’ve spent my career developing and financing the companies that supply these profoundly powerful tools. For the most part, I thought of them as harmless, and I believed my job was simply to make the tools better so that others would use them to improve the world. Only in recent years have I become aware of and concerned about their serious side effects. And so I have decided to study them and do my best to explain those effects to the world. Here’s what I’ve learned.

First, it wasn’t always this way. Our relationship with tools dates back millions of years, and anthropologists still debate whether it was the intelligence of human-apes that enabled them to create tools or the creation of tools that enabled them to become intelligent. In any case, everyone agrees that after those first tools had been created, our ancestors’ intelligence coevolved with the tools. In the process our forebears’ jaws became weaker, their digestive systems slighter, and their brains heavier. Chimpanzees, genetically close to us though they are, have bodies two to five times as strong as ours on a relative basis and brains about a quarter as big. In humans, energy that would have gone into other organs instead is used to run energy-hungry brains. And those brains, augmented by tools, more than make up for any diminishment in guts and muscle. Indeed, it’s been a great evolutionary trade‑off: There are 7 billion people but only a few hundred thousand chimpanzees.

In the distant past our tools improved slowly enough to allow our minds, our bodies, our family structures, and our political organizations to keep up. The earliest stone tools are about 2.6 million years old. As those and other tools became more refined and sophisticated, our bodies and minds changed to take advantage of their power. This adaptation was spread over more than a hundred thousand generations.

Our social structures evolved along with the tools. Some 10 000 years ago, tribes of roaming hunter-gatherers began to stay in one place to raise crops. Agriculture made cities possible, and with cities came the arts and commerce. As transportation improved and cities grew, it became important to control distant places that supplied food and raw materials. About 6000 years ago, ancient city-states such as Uruk emerged in Mesopotamia and governed the surrounding countryside. Millennia later, Athens, the largest of the Greek city-states, controlled about 2500 square kilometers and most of the Aegean Sea. So far, so good.

But with the invention of movable type in medieval times, followed by other improved ways of connecting—better ships and roads, trains, planes, automobiles, and the Internet—technology raced ahead of us. In our own time the most striking example of the acceleration of technology has been Moore’s Law, under which the density of transistors on chips has doubled every 18 months. The performance of single processors long rose in tandem with the transistor count, and even after that relationship stalled in the mid-2000s, the switch to devices using many processors kept the performance curve pointing upward.

This exponential rise in capability has greatly augmented the pooling of knowledge from different sources to achieve the creative synthesis described by the 19th‑century mathematician and philosopher Henri Poincaré: “To create consists precisely in not making useless combinations, and in making those which are useful and which are only in a small minority…. Among chosen combinations, the most fertile will often be those formed of elements drawn from domains which are far apart.”

Drawn in part from the Internet, the newly created knowledge gets deposited back on the Internet, increasing its scope and accelerating the development of technology. Burgeoning knowledge in turn drives rapid change—it advances technology, transforms business institutions, and changes how markets work and how people interact. Governments, social institutions, and our brains struggle to keep up.

Even the nature of change itself has changed. Living creatures started out evolving in one dimension defined by the physical world and another defined by the biological world. Then came humans, who added a third dimension—the artificial one engendered by tools and technology. Now, with the widespread use of the Internet, a fourth dimension has been added—that of virtual reality, or cyberspace. It is indeed appropriate to consider this last dimension as real and distinct from the tools and technologies of the past, because however fast those things may have changed, the rate of change in the virtual space is much faster. It took a lot of time to build physical infrastructure—railroads, highways, bridges, skyscrapers, and so forth. But in virtual space, entire new infrastructures can arise overnight, as Google and Facebook have proved.

I now believe that our minds, bodies, businesses, governments, and social institutions are no longer capable of coping with the rapid rate of change. And it is obvious that this change is indeed more rapid than any comparable change that came before.

Think of the many years it took Barnes & Noble to build its retail chain of U.S. bookstores. The company set up its first bookstore in 1917, and by 2010 it was operating 717 stores. It took time for the company to find the proper locations, lease them, and stock them with inventory, and still more time to build them into viable businesses. The company was limited in what it could do because only certain physical locations were suitable for retail stores. Compare that long history to the rise of Amazon.com, which started in 1994 and was operating in virtual space throughout the United States by the next year, putting a bookstore in every home that had an Internet connection.

Barnes & Noble responded with an online strategy of its own, one that now gives pride of place to sales of e-books, and the company continues to fight on; meanwhile, competitor Borders was liquidated. Both constitute sterling examples of the “creative destruction” of capitalism, as the economist Joseph Schumpeter put it. But the fact that entire business models can come and go that fast is extraordinary. It also indicates the challenges that rapid change presents to other institutions.

An example is our financial institutions, transformed in the past 20 years by radical innovations, such as the introduction of high-speed trading—in which computers trade securities with other computers—and the immensely complex new investment vehicles known as derivatives. These innovations, enabled by improvements in computing power and telecommunications, have made markets more volatile and played leading roles in the recent worldwide economic meltdown. And our regulatory framework has failed to keep up.

In 2005 about 80 percent of the shares of companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange were traded on its floor or on its proprietary digital system; today only 20 percent are traded there. Most of the other shares are traded on alternative systems that have cropped up, systems in which many of the old rules and regulations no longer apply. High-frequency traders have exploited these lightly regulated trading systems. In the United States, computer-driven algorithms now execute 60 percent of all stock trades. One result was the Flash Crash on 6 May 2010, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 1000 points in a matter of minutes. Although it recovered 600 points of the loss minutes later, the episode shows us just how little we understand about high finance and how vulnerable we are to its vagaries.

European stock exchanges have become vulnerable as well. The Better Alternative Trading System, for example, has taken market share away from the London Stock Exchange. Xavier Rolet, CEO of the London Stock Exchange, has tried to counter this threat by diversifying the exchange’s business. Whether this strategy can slow the decline of the London exchange is unclear.

The Internet has also made it easier to participate in the over-the-counter market in derivatives—which are essentially side bets on the value of assets. In 2000, the notional value of these OTC derivatives was US $60 trillion; by 2007 it had risen to $600 trillion. Losses on these derivatives played a major role in the 2008 financial crisis and are still causing problems today. In late 2009, a little-known company called Markit Group created the iTraxx SovX index, which made it easier to use derivatives to place bets on the possibility of a Greek default. As the cost of insuring Greek debt based on the iTraxx SovX rose, investors shunned Greek bonds, making it harder for the country to borrow. Of course, the Greek economy was in dire straits anyway, but those problems were aggravated by the new strategies of speculation that technology has made possible.

Regulatory reform has been a case of too little, too late. Basel III, an agreement concluded in 2011 by the banking supervisors of 10 major industrialized countries, is too weak. And in the United States, the 2319‑page Dodd-Frank legislation will probably prove to be too complex to achieve its goal of averting another meltdown. Ultimately, the only way to deal with financial innovation in a virtual world is through international regulatory systems based on commonly accepted principles. But as a former head of the Bank for International Settlements told me, good luck with that. The tools are making the rules.

Evidence is also beginning to pile up that our brains can’t deal effectively with virtual environments. This makes perfect sense: The challenge they pose is barely half a generation old, yet our minds have been shaped by other challenges that date back thousands of generations.

And as we take bodies and brains adapted to physical space and immerse them in virtual worlds, they are not only unable to cope, they respond in unanticipated ways. As Nora Volkow, the director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, has observed, “the technology is rewiring our brains.”

We already know that physical stimuli can cause profound changes in the brain. Studies of combat veterans afflicted with post-traumatic stress disorder, for example, reveal that it produces a persistent and worrying increase in levels of cortisol, a hormone associated with stress. Increasingly we are seeing evidence of similar changes from the stress we experience when moving from the real to virtual worlds.

Linda Stone, formerly a developer of interactive media for Microsoft, has studied the multitasking of those of us who sit in front of computer screens for long stretches of time. She finds some of the cortisol-triggered responses seen in combat veterans, including elevations in heart rate and blood pressure. And in a 2010 paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, Decio Coviello of HEC Montréal and his colleagues concluded that multitasking, by spreading attention among many functions, hurts overall performance. Russell A. Poldrack, a neurobiologist at the University of Texas at Austin, has similarly shown that multitasking retards learning.

Worse, though, is that our brains seem to crave the virtual world, with repeated exposure producing changes that resemble drug addiction. According to Gary Small, a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles, the excitement of getting an e-mail alert causes a release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that reinforces the behavior and thus drives us to crave more such stimulation. Before long, it becomes impossible for people to put down their iPhones and BlackBerries. Dopamine’s effects were shaped by natural selection: It helped to focus our attention so that we wouldn’t be eaten by tigers. These days, it is facilitating our consumption by e-mail and text messages.

Many experts believe our Internet addiction is similar to that associated with gambling. In both cases, people find it difficult to function normally, have stable family lives, or be effective at work.

It will be years before we fully understand the lasting effects of living in virtual worlds. But until we do, it is best to approach the situation with caution. The main challenge we face is to recognize that we are designed to reside in a slower-paced physical world. This is extremely difficult to accept. We want our news instantaneously. We want to be in touch with everyone at all times. Our careers depend on our being constantly available.

But we have to make a choice: We can design our lives so that we stay in control, or we can cede the control of our lives to our tools.

If we choose the former path, then we are going to have to rethink the way we regulate financial markets, and in this and many other areas, we are going to need new and stronger laws. For example, we will need to guarantee property rights in virtual space to protect our privacy. And we will need to recognize that the nature of our institutions has changed. For many of us, a single corporation—Apple—now dominates our virtual existence: Our virtual lives are bounded by MacBook Airs to the north, iPads to the south, iPhones to the west, and iPods to the east. This company has more power over me than the regulated telephone companies ever did. Should companies like Apple be regulated?

We also have decisions to make. For my part, I have decided to stay in control. I use the miraculous tools of the information age to augment my life in physical space, rather than live in the virtual space and use the physical world to supplement it.

I’m reminded of an observation made to me a while back by John M. Staudenmaier, a historian of technology who is also a Jesuit priest. He pointed out that the quickest way to end a deep and meaningful conversation was to glance at your watch. What would he say today about our ever more tempting smartphones?

I have shut off most alerts and reminders on my computer and smartphone. I check for e-mail on my own schedule, just a few times a day. At home, I have built a physical wall around the virtual world. I let myself read news on my iPad anywhere in my home, but I answer e-mails and conduct business only in my office. I heed Staudenmaier’s advice and never end important conversations by glancing at my smartphone. My iPhone is never present when I am out with my wife, listening to the challenges my kids are facing, or playing and laughing with my grandchildren.

My advice to you is to take control of your tools. I promise your life will be better if you aren’t constantly checking to see if you’ve got mail.

This article originally appeared in print as "Our Tools Are Using Us."

About the Author

William H. Davidow is a cofounder of Mohr Davidow Ventures. He has written widely about how technology influences social institutions, most recently in Overconnected: The Promise and Threat of the Internet, which came out in 2011.