Bitcoin: The Cryptoanarchists’ Answer to Cash

How Bitcoin brought privacy to electronic transactions

There’s nothing like a dollar bill for paying a stripper. Anonymous, yet highly personal—wherever you use it, that dollar will fit the occasion. Purveyors of Internet smut, after years of hiding charges on credit cards, or just giving it away for free, recently found their own version of the dollar—a new digital currency called Bitcoin.

You’ll know it when you see it (strippers who accept tips in bitcoins advertise their account addresses right on their bodies). And more important, if you pay with it, no one needs to know. Bitcoin balances can flow between accounts without a bank, credit card company, or any other central authority knowing who is paying whom. Instead, Bitcoin relies on a peer-to-peer network, and it doesn’t care who you are or what you’re buying.

In the long run, a system like this, which restores privacy to electronic payments, could do more than just put the sneak back into the peek. If enough people take part, Bitcoin or another system like it will give political dissidents a new way to collect donations and criminals a new way to launder their money—while causing headaches for traditional financial gatekeepers.

You may have heard about Bitcoin last year, when the digital currency was briefly a major media story and speculators rushed to cash in on the rising value of bitcoins. Or perhaps you heard about hackers raiding the coffers of the largest online bitcoin exchanges, which coincided with the price of bitcoins plunging. Since January Bitcoin has stabilized. It’s been holding an exchange rate of about US $5.

The dream of an anonymous, independent digital currency—one where privacy is maintained for buyers and sellers—long predates Bitcoin. Despite obituaries in magazine articles from Forbes, Wired, and The Atlantic, the dream is far from dead.

The pursuit of an independent digital currency really got started in 1992, when Timothy May, a retired Intel physicist, invited a group of friends over to his house outside Santa Cruz, Calif., to discuss privacy and the nascent Internet. In the prior decade, cryptographic tools, like Whitfield Diffie’s public-key encryption and Phil Zimmermann’s Pretty Good Privacy, had proven useful for controlling who could access digital messages. Fearing a sudden shift in power and information control, governments around the world had begun threatening to restrict access to such cryptographic protocols.

May and his guests looked forward to everything those governments feared. “Just as the technology of printing altered and reduced the power of medieval guilds and the social power structure, so too will cryptologic methods fundamentally alter the nature of corporations and of government interference in economic transactions,” he said. By the end of the meeting, the group had given themselves a name—“cypherpunks”—and the superhero-like task of defending privacy across the digital world. In just a week, cofounder Eric Hughes wrote a program that could receive encrypted e-mails, scrub away all identifying marks, and send them back out to a list of subscribers. When you signed up, you got a message from Hughes:

Cypherpunks assume privacy is a good thing and wish there were more of it. Cypherpunks acknowledge that those who want privacy must create it for themselves and not expect governments, corporations, or other large, faceless organizations to grant them privacy out of beneficence.

Hughes and May were deeply aware that financial behavior communicates as much about you as words can—if not more. But outside of cash transactions or barter, there’s no such thing as a private transaction. We rely on banks, credit card companies, and other intermediaries to keep our financial system running. Will those corporations save and even share a dossier of your spending habits? Even using cash requires trust that the bill will maintain its worth. Will governments print too much currency or too little? Many cypherpunks would say that the only way to answer these questions is to build an entirely new system.

Gradually, their mistrust germinated into an anarchist philosophy. Most simply wanted to be able to buy things without someone looking over their shoulders. But others on the mailing list imagined liberating currency from governmental control and then using it to lash back at their perceived oppressors.

Jim Bell, a onetime Intel engineer, took these fancies further than anyone, introducing the world to an odious thought experiment called an assassination market. Citizens needed an effective way to punish politicians who acted against the wishes of their constituents, he reasoned, and what better punishment than murder? With an anonymous digital coin, argued Bell, you could pool donations from disgruntled citizens into what amounts to bounties. If a politician made enough people angry, it would only be a matter of time before the price pushed him out of office or cost him his life. Bell’s essay, “Assassination Politics,” eventually attracted the attention of federal agents. His spiral through the U.S. court system started with an IRS raid in 1997 and ended this March with his release from prison.

While cypherpunks like Bell were dreaming up potential uses for digital currencies, others were more focused on working out the technical problems. Wei Dai had just graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in computer science when he created b-money in 1998. “My motivation for b-money was to enable online economies that are purely voluntary,” says Dai, “ones that couldn’t be taxed or regulated through the threat of force.” But b-money was a purely personal project, more conceptual than practical.

Around the same time, Nick Szabo, a computer scientist who now blogs about law and the history of money, was one of the first to imagine a new digital currency from the ground up. Although many consider his scheme, which he calls “bit gold,” to be a precursor to Bitcoin, privacy was not foremost on his mind. His primary goal was to turn ones and zeros into something people valued. “I started thinking about the analogy between difficult-to-solve problems and the difficulty of mining gold,” he says. If a puzzle took time and energy to solve, then it could be considered to have value, reasoned Szabo. The solution could then be given to someone as a digital coin.

In Szabo’s bit gold scheme, a participant would dedicate computer power to solving cryptographic equations assigned by the system. “Anything that works well as a proof-of-work function, producing a specific binary string such that it can be proved that generating that string was computationally costly, will work,” says Szabo. In a bit gold network, solved equations would be sent to the community, and if accepted, the work would be credited to the person who had done it. Each solution would become part of the next challenge, creating a growing chain of new property. This aspect of the system provided a clever way for the network to verify and time-stamp new coins, because unless a majority of the parties agreed to accept new solutions, they couldn’t start on the next equation.

When attempting to design transactions with a digital coin, you run into the “double-spending problem.” Once data have been created, reproducing them is a simple matter of copying and pasting. Most e-cash scenarios solve the problem by relinquishing some control to a central authority, which keeps track of each account’s balance. DigiCash, an early form of digital money based on the pioneering cryptography of David Chaum, handed this oversight to banks. This was an unacceptable solution for Szabo. “I was trying to mimic as closely as possible in cyberspace the security and trust characteristics of gold, and chief among those is that it doesn’t depend on a trusted central authority,” he says.

Bit gold proved that it was possible to turn solutions to difficult computations into property in a decentralized fashion. But property is not quite cash, and the proposal left many problems unsolved. How do you assign proper value to different strings of data if they are not equally difficult to make? How do you encourage people to recognize this value and adopt the currency? And what system controls the transfer of currency between people?

After b-money and bit gold failed to garner widespread support, the e-money scene got pretty quiet. And then, in 2008, along came a mysterious figure who wrote under the name “Satoshi Nakamoto,” with a proposal for something called Bitcoin. As is fitting for the creator of a private digital currency, Nakamoto’s true identity remains a secret. “I’ve never heard of anybody who knew about that name earlier,” says Szabo. “And I’m not going to speculate on who he may or may not be.”

To create a working system, Nakamoto started with the idea of a chain of data, similar to bit gold. But rather than creating a chain of digital property, Bitcoin records a chain of transactions.

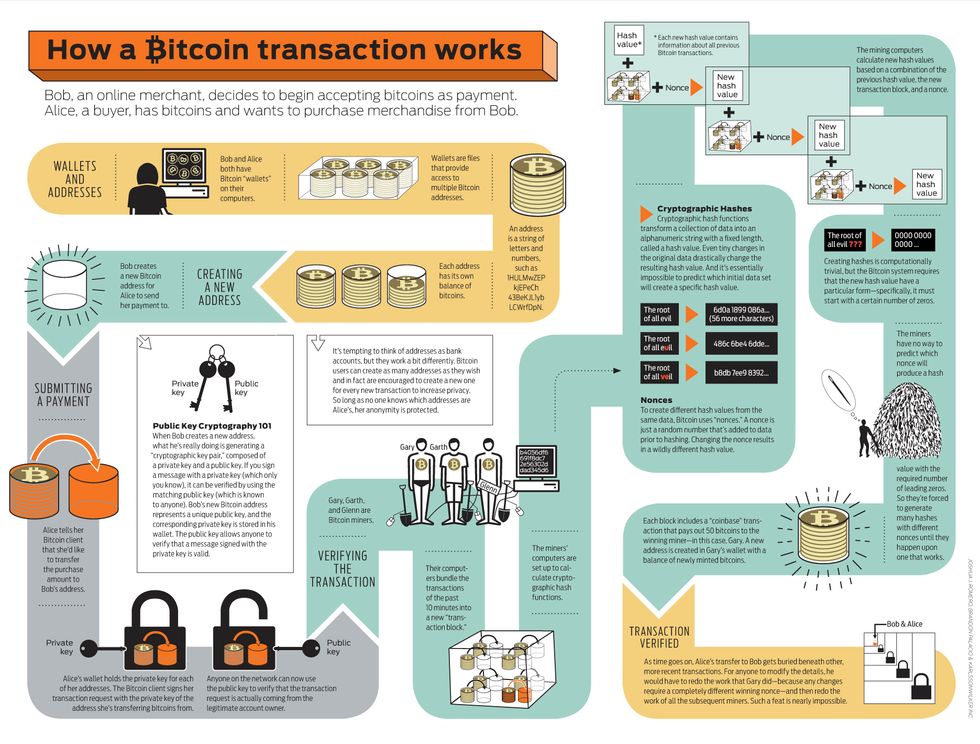

The simplest way to understand Bitcoin is to think of it as a digital ledger book. Imagine a bunch of people at a table who all have real-time access to the same financial ledger on laptops in front of them. The ledger records how many bitcoins each person at the table has at a given time. By necessity, the balance of each account is public information, and if one person wants to transfer funds to the person sitting across from him, he has to announce that transaction to everyone at the table. The entire group then appends the transaction to the ledger, which they all need to agree on. In a system like this, money never has to exist in a physical form, and yet it can’t be spent twice.

This is basically how Bitcoin works, except that the participants are spread across a global peer-to-peer network, and all transactions take place between addresses on the network rather than individuals. Address ownership is verified through public-key cryptography, without revealing who the owner is.

The system turns traditional banking privacy on its head: All transactions are made in public, but they’re difficult to link up with a human identity. Maintaining the dissociation takes vigilance on the part of the Bitcoin user and careful decisions about which outside applications and exchange methods to use, but it can be done. “Anonymity is typically compromised by means outside of Bitcoin’s control, in other words,” says Jeff Garzik, who is on the team of programmers now responsible for developing the Bitcoin software. Bitcoin is often described as providing pseudoanonymity, by creating enough obfuscation to provide users with plausible deniability.

People who own bitcoins have a program—called the Bitcoin client—installed on their computers to manage their accounts. When they want to access their funds, they use the client to send a transaction request. The innovation of Bitcoin is to use the processing of these transaction requests as the mechanism for creating new currency.

As requests pile up in the system, individual computers, running “mining” programs, bundle them into chunks called transaction blocks. Before each block of transactions becomes part of the accepted Bitcoin ledger, or block chain, the mining software must transform the data using cryptographic hash equations. The Bitcoin client accepts the resulting hash values only if they meet strict criteria, so miners typically need to compute many hash values before stumbling upon one that meets the requirements. That process costs a lot of computing power—so much that it would be prohibitively difficult for anyone to come along and redo the work. Each new block that gets added and sealed strengthens all the previous blocks on the chain.

The “miner” whose computer first finds an acceptable hash value is rewarded with newly minted bitcoins. The Bitcoin system adjusts the difficulty of the hashing requirements to control the minting rate. To its proponents, this is one of Bitcoin’s biggest attractions: Unlike the printing of “fiat” currency, which can be done on demand, the creation of Bitcoins will gradually taper until it reaches a limit of 21 million coins.

As more and more miners compete to process transactions, mining requires more computing power. Brock Tice, who mines bitcoins in St. Paul, Minn., has a whole room stuffed full of enough mining computers to heat his office in the winter. But Tice first became interested in the network for a different reason. He thought it would be a better way to accept money from customers online.

In 2009, he began selling little blue canary-shaped night-lights from his home in New Mexico. He quickly lost patience with all the standard payment options. “I had been thinking for a while that something like Bitcoin was needed,” he says. “I run a couple of small businesses, and taking or making payments is just such a huge pain.” Every time a customer pays with PayPal, for instance, Tice hands over 2.9 percent of what he charges plus a small fee. For international sales, he pays even more. The rates for Google Checkout and credit cards are about the same, and for each one he has to open an account with the company processing the transaction, and then trust that it will eventually hand over the money. After reading about how Bitcoin works, Tice decided to include it as a payment method on his website.

For merchants like Tice, the benefits are obvious. In addition to relieving him of fees (at least for now—Bitcoin has an optional mechanism in place for miners to collect fees in the future), Bitcoin transactions won’t open him up to claims of credit card fraud. In Bitcoin, all transactions are irreversible.

On the other hand, unlike credit card users, consumers paying with bitcoins have no way to get their money back if Tice never ships the item. But as with any financial transaction, some level of trust is still required. And some customers would prefer to trust a merchant to make good on a sale than trust them to protect sensitive data. Last spring, hackers broke into the Sony PlayStation Network and swiped a trove of private account details—credit card numbers, birthdays, log-ins, passwords, home addresses, and all the names associated with them. Just days later, it happened again, and within a week the security of more than 100 million Sony accounts was at risk. “I think Bitcoin really has the potential to change our expectations about what information we give merchants,” says Gavin Andresen, Bitcoin’s project leader.

The Bitcoin system has had its own hacking problems. Other than a few die-hard miners, most people buy bitcoins at an exchange where you pay dollars, euros, or whatever and get bitcoins in return. These exchanges also allow merchants to convert their bitcoin collections into other currencies. Unfortunately, the security of the exchanges hasn’t been as good as the Bitcoin client itself. The largest online exchange, Mt. Gox, lost 500 000 bitcoins to hackers in June 2011, which sent the price barreling down. Anyone who invests in a bitcoin better understand that it’s going to be more volatile than the dollar, says Michael Kagan, the managing director at ClearBridge Advisors, an investment firm in New York City.

Even with the ups and downs, many of Bitcoin’s early adopters amassed their virtual fortunes when mining was easy, so they have an incentive to keep the system going (assuming they didn’t cash out at the peak of the bubble). It’s possible they are hoarding the currency, as the economist Paul Krugman speculated they would, waiting for the price to rise again as mining becomes more competitive and expensive. And while Bitcoin’s fixed minting rate helped attract its most fervent early adopters, it also made the barrier to entry much higher for people who want to join now. “If anything is the Achilles’ heel of Bitcoin, that probably is it,” Szabo says.

If Bitcoin does fail, it may die in an act of cannibalism. Nakamoto introduced the block chain, but cryptographers are now already working on improvements. The minting rate is only one of many things that could be tweaked. “Bitcoin is the first of a new breed,” says Garzik. “People will learn from Bitcoin and build something better, or Bitcoin’s critical mass will force it to evolve and learn from its own mistakes.”

This article originally appeared in print as “The Cryptoanarchists Answer to Cash.”

About the Author

Morgen E. Peck never saw the point in writing about money or finance. Then she attended a conference on the cryptocurrency Bitcoin and talked to anarchists, programmers, bankers, cryptographers, libertarians, finance lawyers, and a game show host. From this crucible of ideas, she emerged quite altered. “I’d like to personally thank Satoshi Nakamoto [Bitcoin’s supposed creator] for finally making money interesting enough to write about,” she says.