The Automotive Black Box Data Dilemma

Now that your car records what you do behind the wheel, can you swear it to secrecy?

Built into the framework of U.S. citizens’ civil liberties is the right to privacy. Though not specifically mentioned in the U.S. Constitution, privacy is cherished as a catchall concept that limits government intrusion into people’s lives and establishes boundaries meant to protect one citizen from another. But the framers of the Constitution could not have foreseen the electronic systems that now threaten to modify the definition of privacy or abolish it entirely.

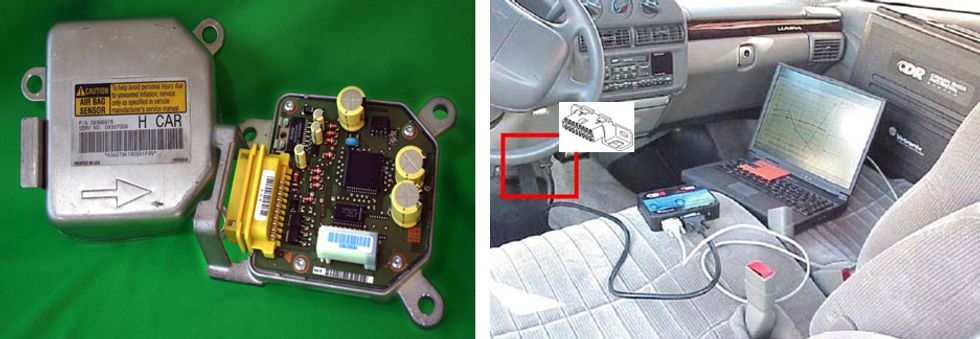

Automobile safety systems, which are networked throughout the body of your car, generate a blizzard of data (likely without your knowledge) and store it in a nondescript box the size of a deck of cards. The gadget, called an event data recorder (EDR), is a less-refined version of the so-called black box carried by aircraft. Initially, EDRs were supposed to help researchers and automakers make refinements to the systems intended to keep cars from crashing and people from dying. But it wasn’t long before these devices were eyed as tools to help authorities figure out what a driver was doing in the moments before a crash—be it eating, shaving, or gargling with vodka. (Before EDRs, drawing such conclusions required autopsies and a series of educated guesses based on things like skid marks.)

What’s more, new standards regarding the performance of automotive black boxes and guidelines for retrieving data after a crash are set to go into effect in the next several months, raising privacy issues and setting up a clash between law enforcement and privacy advocates that could be fought all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The high court is already grappling with unprecedented cases involving the freedom from search and seizure provided by the Fourth Amendment and the privilege against self-incrimination provided by the Fifth Amendment.

In January, the Supreme Court ruled in a similar case— United States v. Jones —which involved digital monitoring of a driver’s behavior. In that case, police secretly planted a GPS tracking device on a suspected drug dealer’s car and monitored his whereabouts for 28 days. The high court ruled that the evidence obtained using the device could not be used against the suspect because the police failed to obtain a warrant. At a minimum, the court ruled, placing the tracker represented an illegal trespass.

Technology is sure to play an ever greater role in courtroom drama, especially as it relates to the sharing of digital data. But in contrast to the United States v. Jones case, the focus will be on electronic devices that are already in place when you drive your car off the dealer’s lot.

According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), 85 percent of new vehicles come equipped with black boxes. Still, the average driver has no idea that in the event of a crash, data stored in the box details how the car was being driven in the moments before impact.

Although black boxes are not mandatory by NHTSA rules, starting with 2013 models, EDRs must keep a record of 15 discrete variables in the seconds before a crash. Among them are the car’s speed, how far the accelerator was pressed, the engine revolutions per minute, whether the driver hit the brakes, whether the driver was wearing a safety belt, and how long it took for the airbags to deploy. A black box must also stand up to the initial impact so that it can capture data for at least two more hits in a multievent crash, such as when two moving vehicles collide and one bounces off, sideswipes a parked car, and then slams into a tree.

There is currently pending legislation (the Motor Vehicle and Highway Safety Improvement Act of 2011, or Mariah’s Act) that would make EDRs mandatory for 2015 models. The bill also calls for the collection of even more data about your driving habits. And here’s where the tug of war between law enforcement and privacy advocates begins.

NHTSA rules [PDF] require automakers to make commercially available tools for retrieving black box data. The rules also mandate that the car’s owner’s manual contain a brief statement indicating that the vehicle includes an EDR and explaining what it does. And although Mariah’s Act says that any data in a vehicle’s black box is the property of the owner or lessee of the vehicle in which the data recorder is installed, privacy advocates fear what could happen if the information is misappropriated. Why? Slowly but surely, EDR data is ending up in court, affecting the verdicts in criminal and civil cases.

Case in point: The Santa Clara County District Attorney’s Office in San Jose, Calif., prosecuted the driver of a vehicle that in May 2006 struck and killed a 15-year-old pedestrian in a crosswalk. Conventional accident reconstruction techniques estimated that the driver was traveling at roughly 90 kilometers per hour in a 72 km/h zone. Subsequently, the prosecutor’s office allowed the driver to plead guilty to hit and run—a lesser offense than vehicular manslaughter, which is what it had initially aimed to prove.

Police investigators were initially unaware, however, that the driver’s vehicle, a GMC Yukon, was equipped with an EDR capable of recording precrash data. (This underscores the extent to which EDRs’ capabilities have been an open secret.) A year after the accident, authorities found out that the data they needed was available and recovered it. Prosecutors discovered that the driver had actually been traveling at 122 km/h. The box also revealed that the driver applied the brakes at some point between 2.1 and 1.3 seconds before he struck the pedestrian, lowering the SUV’s speed to about 97 km/h at impact. With that evidence in hand, Charles G. Gillingham, the attorney who prosecuted the case, withdrew the plea agreement and proceeded to trial on the vehicular manslaughter charge and other, lesser charges. The driver was convicted.

“I don’t see how there can be an expectation of [EDR] privacy in a criminal case,” Gillingham insists. “When you’re driving on public land, you give up expectation of privacy.” Challenged on whether that statement conflicts with longstanding U.S. principles of search and seizure, he says, “There’s an expectation of privacy with regard to my body or my home; that’s very much different than the engine of my car.”

But there is a growing cadre of people who disagree with Gillingham, including the Court of Appeals of California, Sixth District, which overturned the manslaughter conviction in February 2011 on the grounds that law enforcement did not secure a search warrant to retrieve the data. (The other convictions were left intact.)

In the first civil lawsuits and criminal cases involving cars equipped with EDRs, auto companies claimed that they owned the data; courts eventually began ruling that it belongs to vehicle owners and lessees. But without federal laws governing who should have access to black box data, the matter was left to the states. Thus far, only 13 states have passed laws governing the ownership of EDR data. And this geographical patchwork means that a car owner’s rights depend on where he is when his fender gets bent. In the 37 states without EDR laws, there are no ground rules preventing insurance companies from obtaining the data—sometimes without the vehicle owner ever knowing that the data existed—says Dorothy Glancy, a lawyer and professor at the Santa Clara University School of Law, in California, who has written extensively about privacy and transportation.

Many in the law-enforcement community insist that the constitutional protections that limit searches of private property and keep the government from compelling people to divulge incriminating information don’t apply to a vehicle’s electronic systems, but privacy advocates strongly disagree. “People should not relinquish their Fourth Amendment rights merely because of the location of their information,” says John Tomaszewski, general counsel at TRUSTe, a firm that certifies that the security and privacy measures taken by websites are sufficient to ensure that the personal information supplied by visitors (and customers at e-commerce sites) is safeguarded.

Marc Rotenberg, executive director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) in Washington, D.C., says the reason to limit access is simple: “Your car is spying on you, collecting data about your habits that could be used by insurers [to set price quotes and policy parameters] as well as in a civil case or in a criminal matter.” Then there is the matter of data reliability, says Rotenberg. In the aftermath of an auto accident, the driver may insist that he or she was driving at one speed, while the EDR data suggests a much higher rate of speed. “What does the driver do if the data is faulty but the auto insurer and the manufacturer say it is correct? The driver is pretty much stuck,” says Rotenberg.

Tomaszewski concurs with Rotenberg’s point about the potential for conflict over data reliability and security, adding that he is not sure whether EDR data will regularly stand up in court. “Just because the data was obtained with a warrant doesn’t mean [a judge will allow an attorney to present that information for a jury to hear],” he says.

Tomaszewski notes that there is an evolving body of law around electronic evidence. Somebody is going to argue that presenting EDR data violates a basic principle of U.S. jurisprudence encoded in the Sixth Amendment, he says, which is the right of the accused to have his attorney cross-examine any witnesses testifying against him. The lawyer will insist that the black box data fits the description of testimony and move to have it ruled inadmissible “because the defendant can’t interrogate its source code to ensure that every bit of data was captured and recorded exactly as it should have been,” says Tomaszewski.

“I’m still concerned that what we have to fear about EDRs is not their capabilities but how these devices could be used in the future,” says Thomas M. Kowalick, who has written several books about EDRs, including Black Box: What’s Under Your Hood? Kowalick, who heads the IEEE EDR standards-making effort ( IEEE 1616 [PDF]), fears what law enforcement, insurers, and would-be criminals intent on collecting information about a driver’s identity and driving habits might do with this information. He has been championing the use of a lockable mechanical cover that would block access to a car’s OBD-II port usually located under the dashboard. (In addition to being the place where EDR data-collection tools are plugged in, the port is where automotive technicians seek signals that indicate why a “Check Engine” light has appeared.)

Kowalick successfully lobbied to have some of the elements of the IEEE standard—including the lockout device—included in Mariah’s Act, the auto-safety legislation still wending its way through Congress. “More emphasis is needed on sealing the data at the OBD-II port, therefore establishing a chain of custody and preventing tampering,” says Kowalick.

But W.R. “Rusty” Haight [PDF], director of the Collision Safety Institute, in San Diego, says that installing such a lockout device provides a false sense of security to car owners who may be worried about the police accessing their cars’ data and finding out that they were speeding or doing other illegal things. “It’s a stupid idea,” he says, referring to the push to make lockout devices mandatory. “It would be painfully simple to bypass,” he adds, “because there are exposed wires on the backside of the port that you can access with a couple of pairs of ferret clips. You just need to know which ones correspond to which pins [inside the port].”

Asked whether it was still possible to access the EDR if manufacturers found a way to make the back of the port more secure, Haight didn’t hesitate: “Recommended practice is to use the OBD-II port, but cables can go directly to the [airbag control] module [where the EDR is located], which is not a big deal to do.” Bosch Diagnostics’ Crash Data Retrieval (CDR) system is one of several such devices that can image the data right from the black box and make it downloadable.

So if there are workarounds for accessing the data, then why the insistence on a lockout device? By installing one, Gillingham says, the vehicle’s owner is “evidencing a subjective expectation of privacy.” In other words, the lockout device is the equivalent of a “Do Not Enter” sign. “The government has to comply unless the authorities have a search warrant or some other court order,” says Gillingham.

It’s possible that the verdict in a legal case might come down to whether a car owner had a lockout device installed and the police broke in anyway. Gillingham likened this scenario to a home with a bay window. Having the curtains open, says Gillingham, indicates that you don’t mind someone walking along the sidewalk seeing what’s going on inside. But once you draw the curtains, you are signaling your expectation to privacy and invoking the right to it.

But wireless technology may already be making the lockout device inconsequential. An attorney with expertise in electronic-data privacy noted that all of BMW’s vehicles now come with an EDR that, in addition to capturing performance data, is capable of relaying a car’s information to a local dealership so that appointments for scheduled maintenance can be made automatically.

But, the lawyer asks, what if the state police showed up at a dealership and demanded to see how fast all of its customers were driving during the previous week? Plucking the EDR data from one car would require a search warrant; it’s covered by the Fourth Amendment. But getting the same information about dozens of drivers from the dealer would not require a warrant, because a firm’s business records don’t have the Fourth Amendment privilege. “That’s what scares me,” says the attorney. “Because catching speeders this way could represent a not-trivial revenue stream for municipalities, the temptation to take that step might be difficult to resist.”

With such strong opinions on both sides, it seems clear that whether or not Mariah’s Act is signed into law, the arguments over what vehicles should be recording, who should have access to that information, and the limits of its use will continue for years to come.