Samantha from “Her.” She was smart, feisty, and sometimes pensive. Sam was easy to talk to and brimming with personality.

The AI from Spike Jonze’s 2013 movie caught our attention not just because it had the knowledge base of a thousand IBM Watsons, but also because conversations with Samantha were like chats with a close friend.

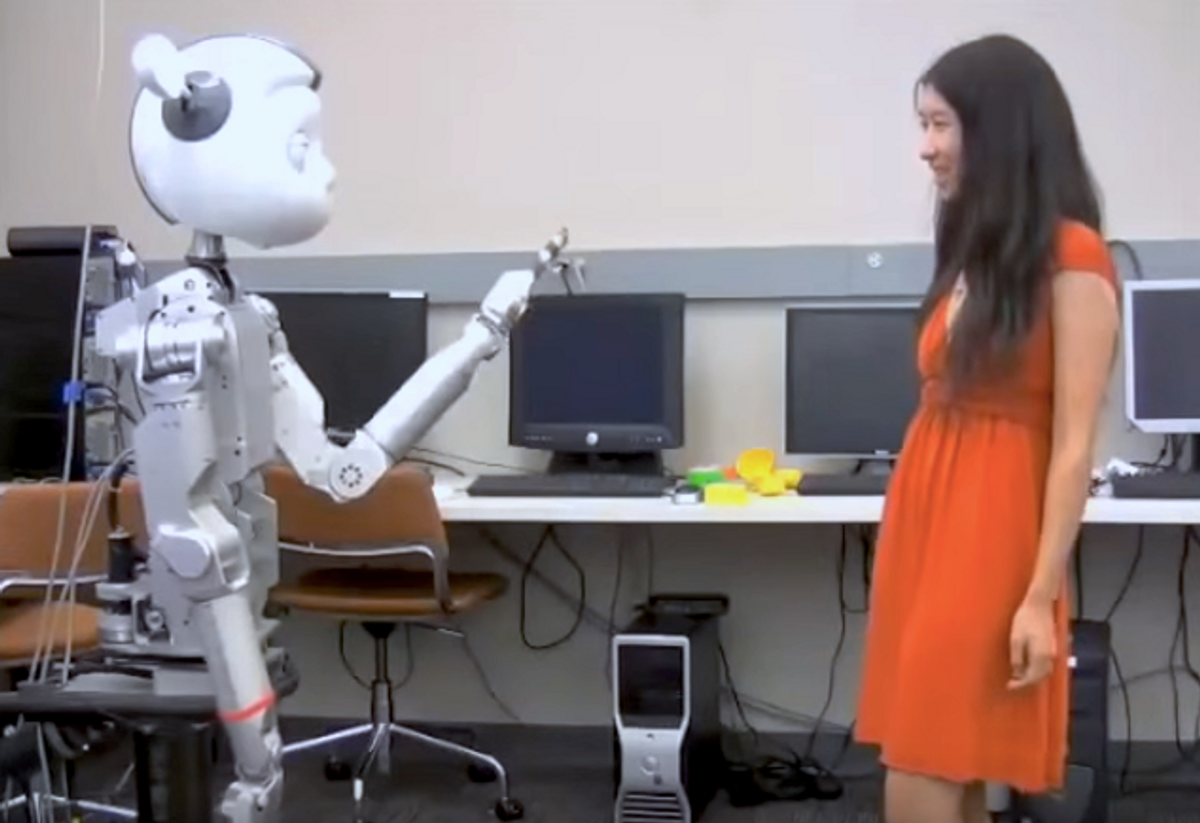

Over the last few years, robot researchers Dr. Crystal Chao and Professor Andrea Thomaz at Georgia Tech have been devising a new way to build humanity and personality into human-robot dialogues. It starts with rethinking the way we talk to machines.

Bringing back the coffeehouse chat

You see, today’s AI dialogue systems or chat bots all work with the same underlying principle. The AI talks, then the human talks, then the AI talks... It’s like a walkie-talkie exchange where each message has to have a clear beginning and end.

But humans don’t talk like that. When two people have a casual chat, they speak in a flow of half-phrases, interrupting, laughing, saying “uh huh.” So the first part of Chao and Thomaz’s work is a new way to model conversations with AI. They’ve gotten rid of formal turn-taking as we know it today. They’re bringing back the coffeehouse chat.

Here’s how it works. For those of you programmers out there, you’ll know the concept of a mutex. A mutex is a way to grab hold of a shared resource, so only one piece of code can access it at a time.

In a human-robot dialogue, the shared resource is the “conversational floor,” or the speaking turn. Only one person can “seize the floor” and talk at a time (or else you’re talking over each other.)

By grabbing hold of the conversational floor whenever it’s free (i.e. there’s silence), both the human and the bot can insert comments into the mix anytime, take the conversation in new directions naturally, instead of waiting for an entire turn to complete.

Forget your conversations with Siri, where your words are bound within a *bing* and a *ba-ding*. Siri (and Google Now, Cortana, and other voice-based assistants) brought big advances to speech recognition, natural language processing, and speech synthesis. But to make human-robot dialogues better, we’ll have to improve not only what robots say but how they say it. What we need is for these interactions to be more like the dynamic conversations in “Her.”

Personality using tricks from improv theatre

The second part of Chao’s work involves modulating the speaking personality of the robot, using simple dynamics and timing. Just as Samantha could at one moment be assertive, outgoing, and active, she could later take a more passive, empathetic role while listening to problems.

But how might these personality traits be built into a robot? Chao tells us that the intuition came from the arts:

“The inspiration for the work actually came from conversations with another group at Georgia Tech that was working on a computational system for improvisational theater! We were all investigating how dominance is expressed through cues in interaction. Some of these are nonverbal cues like body posture, but a large part of conversational dominance is how much a participant seizes and holds on to the speaking floor.

A participant becomes more or less dominant based on how often she interrupts himself or interrupts others, how long her turns are, how long she waits to take a turn, etc. These cues have also been receiving more public attention as women strive to achieve equality in the workplace through how they communicate.”

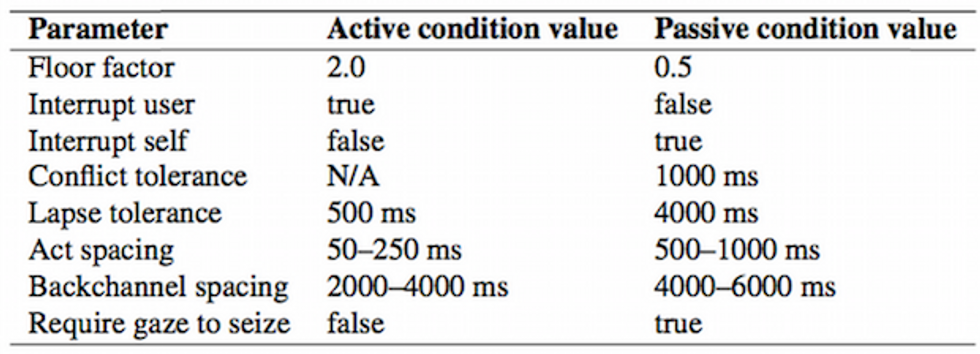

Based on these improv theatre discussions, Chao devised a set of parameters that she can adjust to give the robot a more active or passive attitude:

- Does the robot try to speak as soon as there is a moment of silence?

- Does it interrupt others if they are speaking too long?

- Does it allow itself to be interrupted, or not?

- Is it ok with conflict—talking over each other—and for how long?

- How many seconds of silence does it let tick by before jumping in?

- How much space does it leave between its own sentences?

- How much does the robot give backchannels, such as nodding or "mm hmm"?

- Does it wait for the person to look at them before it's takes its turn to speak?

To test her system, Chao created two experimental conditions, one where the robot used active parameters, and one where the robot maintained passive parameters.

This video below gives an idea of the interaction. For simplicity, the robot here acts as a toddler speaking a protolanguage (don’t try to make sense of the words, it’s mostly babbling), but experiments like this allow the researchers to focus on specific things like the timing and dynamics of the interaction.

Chao found that by simply using the “active” parameters, the robot was perceived as more extroverted. When they used “passive” parameters, people tended to use words such as “shy” to describe the robot.

“When the robot was active, people tended to respond and give feedback to whatever the robot was doing, saying ‘Wow!’, ‘Good job!’,” she says. “When the robot was more passive, people felt obligated to take more initiative. They taught the robot about the objects or told stories about them.”

Chao also warns that care needs to be taken when building personality into a robot. Instead of the expected “outgoing” personality their parameters predicted, some participants called the robot “spacey” or “aloof.”

She explains: “In general, we expect that when the robot is more active and takes more turns, it will be perceived as more extroverted and socially engaging. This is true up to a point. When it’s extremely active, the robot actually acts very egocentric, like it does not care at all that the partner is there, and is less engaging. It actually makes sense; it is sort of like interacting with someone who is self-centered and talks about herself all the time. This is why a balance of being active or passive is really needed.”

Full details on their system is available here, and an article on the balance between active and passive styles (“Real-Time Changes to Social Dynamics in Human-Robot Turn-Taking,” by Justin S. Smith, Crystal Chao, and Andrea L. Thomaz) was presented at IROS in Hamburg earlier this month.