Last month, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed a historic set of vehicle tailpipe-emissions standards, aimed at making two-thirds of all passenger cars zero-emissions by 2032, along with 46 percent of medium-duty trucks (such as delivery vans) and 25 percent of heavy-duty trucks, including 18-wheelers. The proposed standards, which would phase in over the 2027–2032 model years, constitute “the most ambitious pollution standards ever for cars and trucks,” in the words of EPA administrator Michael S. Regan.

As IEEE Spectrum has previously reported, mandating the switchover to electric vehicles and other zero-emission technologies is notoriously hard. But between EPA efforts and the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act, the Biden administration is pursuing a carrot-and-stick bid to boost EV adoption, jump-start homegrown factories and secure supply chains, and blunt China’s troubling dominance over global battery production.

“EPA’s proposal will help the U.S. catch up to global leaders in terms of EV targets as early as 2027.”

—Drew Kodjak, International Council on Clean Transportation

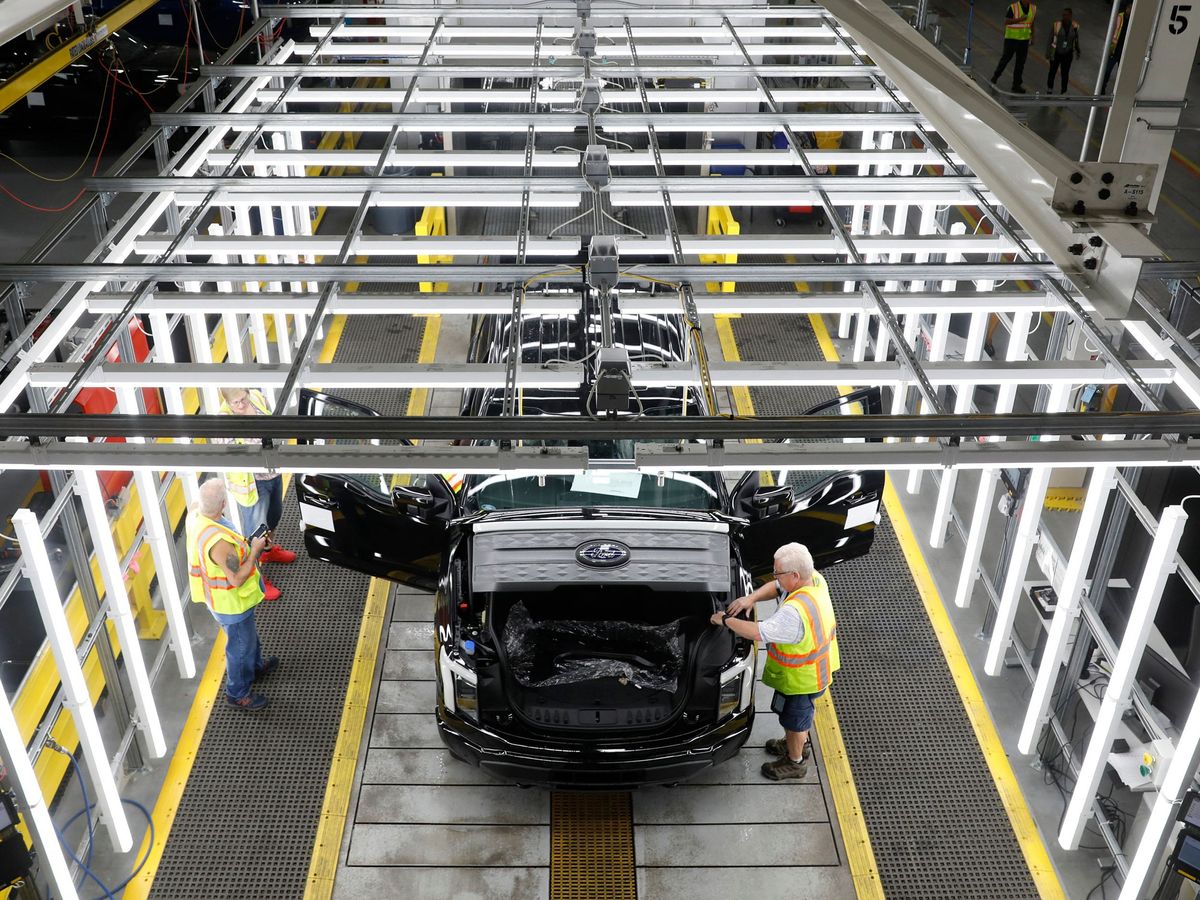

The Inflation Reduction Act already demanded that EVs and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) be built in North America to be eligible for up to US $7,500 in federal consumer tax credits. Beginning 18 April, eligible electrified models must now source an increasing percentage of battery components and minerals from North America or a list of approved trade partners—a list that conspicuously does not include China or Russia. Since the IRA’s passage in August, automakers, suppliers, and battery companies have already committed more than $45 billion in U.S. factory investment, and more than $110 billion since Biden took office.

The IRA’s homegrown manufacturing requirements have also angered some U.S. allies in Europe, Japan, and South Korea, who view them as protectionism. Foreign automakers from BMW to Hyundai Motors—whose EVs are now ineligible for credits—have also raised objections. Even analysts who fully support the IRA’s goals agree that the rules may crimp EV sales until automakers can ramp up North American vehicle and battery production, along with mineral sourcing and processing.

But in an interview, Margo T. Oge, the engineer and former director of the EPA’s office of transportation and air quality, said the IRA and EPA tailpipe rules are a powerful one-two punch to keep the United States competitive in both economic and environmental terms.

“The U.S. is sending a very strong signal to domestic and international companies to come and invest in the U.S., and that we’re serious about climate change,” Oge said.

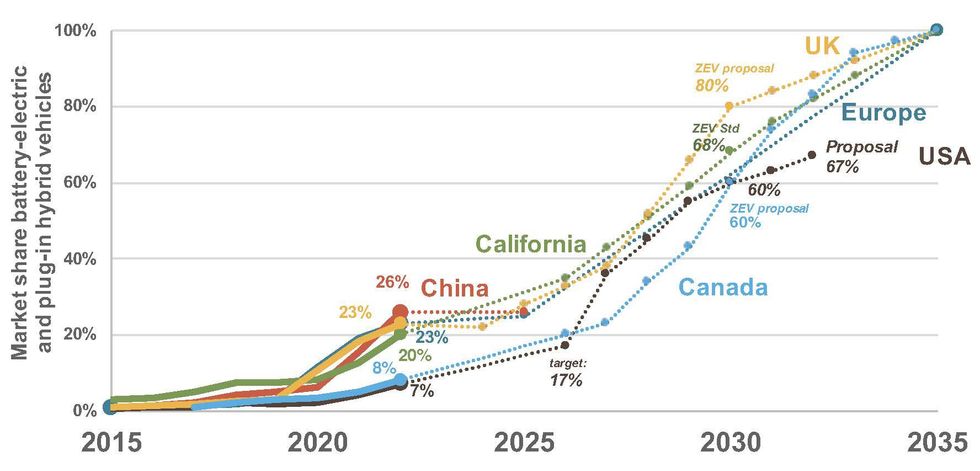

Significantly, Oge said, the proposal aligns the United States’ goals closer to those of Europe and China, where EV adoption has outpaced that of the United States (see graph). European Union countries have approved a landmark law to end sales of new CO2-emitting cars in 2035, including an exception in Germany for models powered by e-fuels that can be proven to generate zero net emissions. China’s President Xi Jinping has pledged the country to achieving net-zero emissions by 2060. The Biden administration is circling 2050 as its own net-zero calendar date, with a target of the United States generating 100 percent of electricity carbon-free by 2035.

If the United States could achieve 67 percent EV market penetration by 2032, Oge said, it would nearly match Europe’s own ambitious timeline. Despite Europe’s current edge and China’s crushing advantage in the battery business, the United States can still reassert itself.

“Some would say we’re too late because of China’s head start,” she said. “But because of the IRA and regulatory efforts from the EPA, the country is moving forward again.”

Drew Kodjak, executive director of the International Council on Clean Transportation, wrote that 7 percent of U.S. buyers are choosing an EV—and 20 percent in California—compared with 23 percent in the E.U. and in the U.K., and 28 percent in China.

When the rules are finalized and implemented, Kodjak said, the “EPA’s proposal will help the U.S. catch up to global leaders in terms of EV targets as early as 2027.”

Kodjak notes that automakers have pledged more than $1 trillion in global electrification efforts. And long-term forecasts now show that U.S. battery production could reach 1 terawatt-hour by 2030, “within striking distance of forecasted battery demand of 1.2 TWh.”

EPA officials say that the rules, if fully enacted, would put the world’s largest economy on pace to cut greenhouse-gas emissions by enough to limit temperature rise to another 1.5 degrees Celsius, and avoid the most devastating effects of climate change. According to the agency’s projections, the new rules would:

- Avoid nearly 10 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions by 2055, equivalent to roughly two years of total U.S. CO2 emissions in 2022.

- Accelerate adoption of technologies that reduce fuel and maintenance costs; the standards would save the average consumer $12,000 over the lifetime of a light-duty vehicle, versus models not held to the standard.

- Reduce oil imports by approximately 20 billion barrels

The transportation sector is the largest U.S. source of greenhouse-gas emissions, according to the EPA, representing 27.2 percent of the total. Passengers cars are responsible for 57 percent of those emissions. The EPA can’t mandate that automakers build and sell electric cars. But under the Clean Air Act, the EPA has precedent and authority to regulate pollution: The proposal essentially sets such strict emissions limits that automakers can meet them only by converting entire their lineups to electricity. Automakers would face fines or other penalties for exceeding an annual fleetwide limit on pollution, including greenhouse gases.

Historically, the Clean Air Act has also allowed California to set emissions standards that are stricter than national rules, a key to California’s triumphant battle over smog in past decades. More than a dozen states have followed California’s lead and adopted its standards. The Trump administration worked to abolish California’s ability to set its own rules. And roughly a dozen state Republican attorneys general have vowed to fight the new EPA rules, which they insist oversteps the agency’s legal authority. Meanwhile, California plans to abolish sales of all internal-combustion-engine cars by 2035, which also dovetails with the EU target.

- Download “The EV Transition Explained” E-book for Free ›

- Why EVs Aren't a Climate Change Panacea - IEEE Spectrum ›

Lawrence Ulrich is an award-winning auto writer and former chief auto critic at The New York Times and The Detroit Free Press.