Who said machines don't have heart? Bioengineers have embedded pulsating human heart cells in a small microfluidic chip to model the effects of drugs on real human hearts.

Animal models are routinely used in the earliest stages of clinical trials, but they often fail to predict human reactions to new drugs because of fundamental differences in biology between species. For instance, the proteins through which ions flow in and out of heart cells can vary in both number and type between humans and other animals.

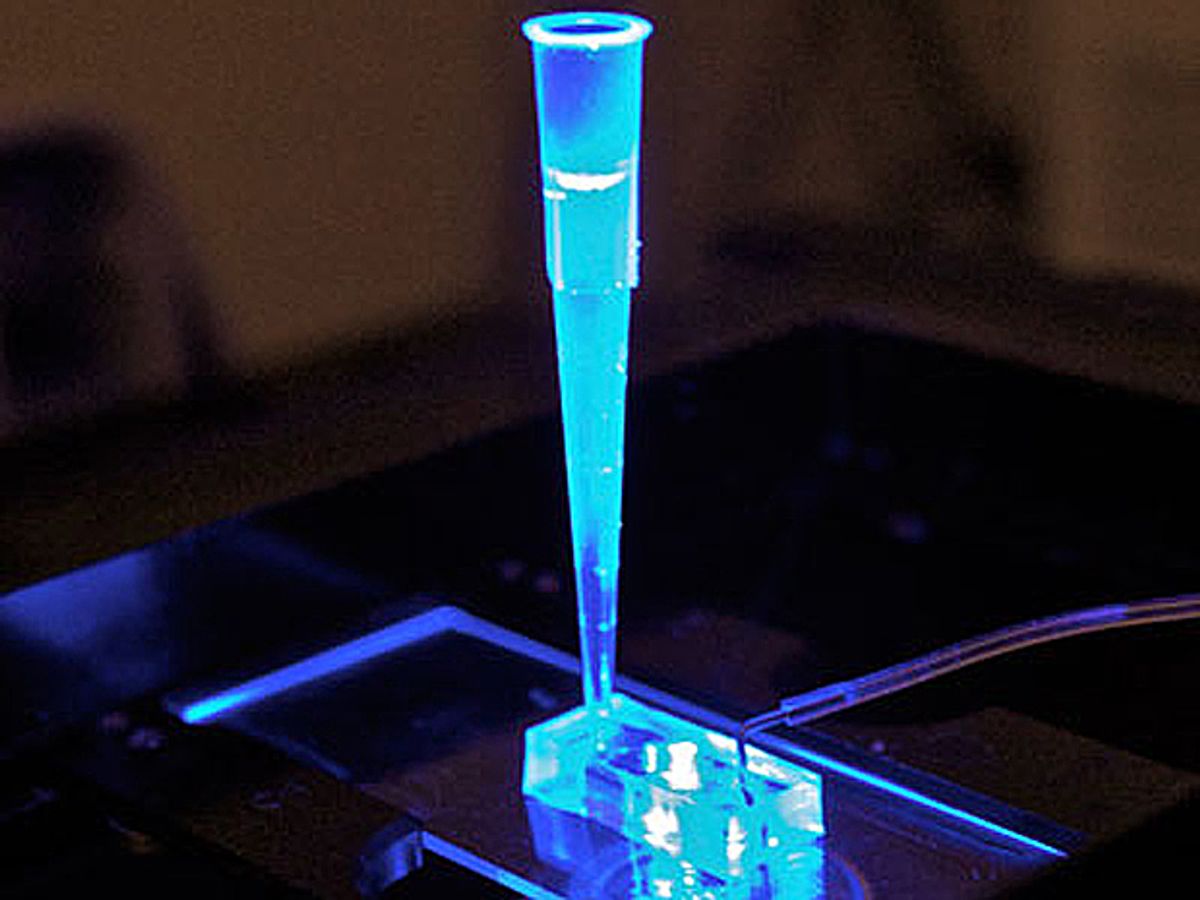

Instead, researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, hope that human heart cells grown on a chip could help replace animal testing. These cells are derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells, which are adult cells chemically modified to become many different kinds of tissue. Microfluidic channels around the cells simulate blood vessels, supplying the cells with nutrients and drugs.

The heart cells began beating on their own at a normal rate of 55 to 80 beats per minute within 24 hours of getting loaded into the device. The bioengineers tested their gadget with four well-known heart drugs, and the cells reacted as predicted — for instance, after a half-hour’s exposure to isoproterenol, a drug used to treat bradycardia (slow heart rate), the cells on the device increased their activity to 124 beats per minute.

One aim for this organ-on-a-chip is to one day help screen potential new heart drugs and see how real human hearts might respond. The heart cells in this device remained alive and functional for several weeks, during which time they could be used to test a variety of drugs, the researchers said in a press release.

The bioengineers noted their heart-on-a-chip could be modified to model human genetic diseases, or it could test how an individual might respond to a drug. One day, if it was combined with similar devices—say, a liver-on-a-chip —the combined system could study the impact of drugs on multiple interacting organs.

The scientists detailed their findings online 9 March in the journal Scientific Reports.

Charles Q. Choi is a science reporter who contributes regularly to IEEE Spectrum. He has written for Scientific American, The New York Times, Wired, and Science, among others.