The violet ray machine has an awesome name that conjures up images of cartoon supervillains taking out Gotham, but its actual history is even odder—and it includes a superhero, not a villain.

The technology underpinning the machine begins with none other than Nikola Tesla and his eponymous coil. After Tesla and others made some refinements to the device, an influential clairvoyant named Edgar Cayce popularized violet ray machines for treating just about every kind of ailment—rheumatism and nervous conditions, acne and baldness, gonorrhea and prostate troubles, brain fog and writer’s cramp. Even Wonder Woman had her own health-restoring Purple Ray device. During the first half of the 20th century, a number of companies manufactured and sold the machines, which became ubiquitous for a time. And yet the scientific basis for the healing effects of violet rays was scant. So what accounted for their popularity?

The cutting-edge tech of the violet ray machine

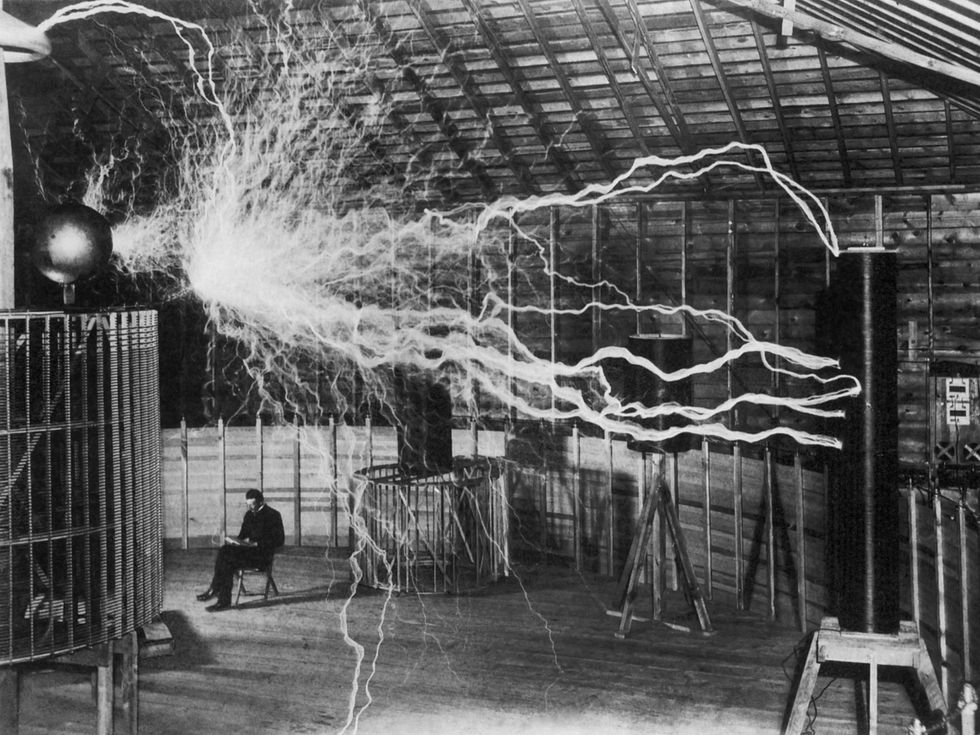

Violet ray machines employ a Tesla coil, also known as a resonance transformer, to produce a high-frequency, low-current beam, which is then applied to the skin. Nikola Tesla kicked off this line of invention after traveling to Paris during the summer of 1889 to attend the Exposition Universelle. There he learned of Heinrich Hertz’s electromagnetic discoveries. Intrigued, Tesla returned to New York City to run some experiments of his own. The result was the Tesla coil, which he envisioned being used for wireless lighting and power. In April 1891, he applied for a U.S. patent for a “System of Electric Lighting,” which he received two months later. It would be the first in a series of related patents that spanned more than a decade.

In May of that year, Tesla unveiled his wondrous invention to members of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, during a lecture on his “Experiments with Alternate Currents of Very High Frequency and Their Application to Methods of Artificial Illumination.” He continued to test different circuit configurations and patented some (but not all) of his improvements, such as a “Means for Generating Electric Currents,” U.S. Patent No. 514,168. After more years of tinkering, Tesla perfected his resonance transformer and was granted U.S. Patent No. 1,119,732 for an “Apparatus for Transmitting Electrical Energy” on 1 December 1914.

Tesla promoted the

medical use of the electromagnetic spectrum, suggesting to physicians that different voltages and currents could be used to treat a variety of conditions. His endorsement came at a time when trained doctors as well as shrewd hucksters were already experimenting with electrotherapy and ultraviolet light to help patients or to make a buck, depending on your perspective.

The market was perfectly primed for the violet ray machine, in other words. Tesla himself never commercialized a medical device based around his coil, but others did. The French physician and electrophysiologist Jacques-Arsène d’Arsonval modified Tesla’s design to make the device safer for human use. It was further improved by another French doctor and electrotherapy researcher, Paul Marie Oudin. In 1893, Oudin crafted the first working prototype of what eventually became the violet ray machine. Four years later, Frederick Strong developed an American version.

An influential clairvoyant named Edgar Cayce popularized violet ray machines for treating just about every kind of ailment—rheumatism and nervous conditions, acne and baldness, gonorrhea and prostate troubles, brain fog and writer’s cramp.

Another charismatic individual gets credit for popularizing the device: the psychic

Edgar Cayce. As a young adult, Cayce reportedly lost his voice for over a year. No doctor could cure him, and in desperation he underwent hypnosis. He not only regained the ability to speak, he also began suggesting medical advice and homeopathic remedies. Cayce, who claimed to have had visions from childhood, became a professional clairvoyant, and for the next 40 years he dispensed his wisdom through psychic readings. Out of more than 14,000 recorded readings, Cayce mentioned the violet ray machine almost 900 times. In case you doubt his status as an influencer, Cayce counted Thomas Edison, composer George Gershwin, and U.S. president Woodrow Wilson among his clients.

Was there nothing the violet ray machine couldn’t cure?

The popularity of violet ray machines exploded after 1915, once all of the components for a portable device could be easily manufactured. They could be plugged into a lamp or wall socket or wired to a battery—remember that most homes and businesses in the early 20th century were not yet electrified, and so most manufacturers offered both alternating and direct current options. The machine’s handheld wand consisted of a Tesla coil wrapped in an insulating material, such as Bakelite. The coil produced 1 to 2 kilovolts, which charged a condenser, and then discharged at a rate between 4 to 10 kilohertz when passed over the skin. A voltage selector controlled the intensity of the spark, creating anything from a mild sensation to something quite intense. This video shows the sparks coming from an antique machine:

Glass electrodes—partially evacuated glass tubes known as Geissler tubes—could be inserted into the wand. These came in different shapes depending on their intended use. For example, a rake-shaped attachment worked to massage the scalp, while a narrow tube could be inserted into the mouth, nose, or another orifice. The high voltage ionized the gas within the glass tube, creating the purple glow that gave the device its name.

Numerous manufacturers sprang up to produce the portable machines, including Detroit’s Renulife Electric Co. Founded by inventor James Henry Eastman in 1917, Renulife sold different models for different uses. According to company literature, Model M was its most popular general-purpose product, while Model D was for dentistry, and the tricked-out Model R [pictured at top] had finer regulation of current and a built-in ozone generator to help with head and lung congestion.

In 1917, editors at the Journal of the American Medical Association reported that a violet ray generator certainly couldn’t treat “practically every ailment known to mankind,” as one manufacturer had claimed.

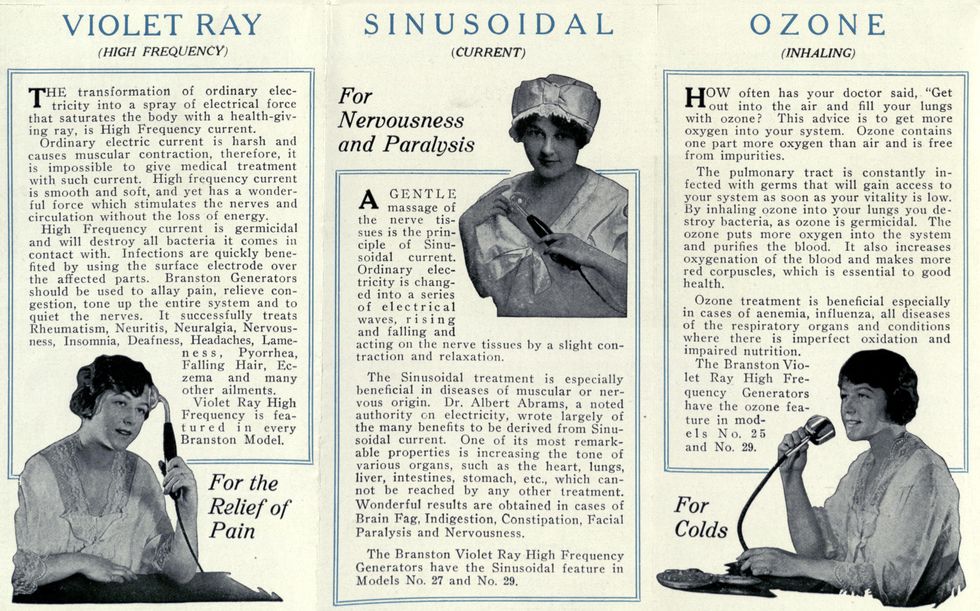

Instructions for the violet ray machines manufactured by Charles A. Branston Ltd. contain an alphabetical list of disorders that could be treated, from abscess to writer’s cramp, with dozens of other ailments in between. Like the Renulife products, the Branston machines also came in different flavors. The Branston machine’s high-frequency mode had germicidal effects and purportedly could be used to cure infections as well as relieve pain. Sinusoidal mode was used to gently massage away nervousness and paralysis. Ozone mode was for inhaling, to treat lung disorders. The Branston devices ranged in price from US $30 for the Model 5B (high-frequency mode only) to $100 for the Model 29 (which had all three modes).

During the first half of the 20th century, manufacturers marketed the machines to doctors and consumers alike. By the time Wonder Woman debuted in her own comic book in June 1942, the violet ray machine was a well-known household technology. So it wasn’t too surprising that the superhero had a machine of her own.

In the very first issue, Wonder Woman’s future love interest, Steve Trevor, is grievously injured in a plane crash. Seeking to cure his wounds, Diana works tirelessly for five days to complete her Purple Ray machine—but she’s too late. Trevor has died. Undeterred, Diana bathes her patient in the glowing light of the machine. The result might have embarrassed even the admen who wrote the promotional copy for Branston’s products: Wonder Woman’s Purple Ray brings Trevor back to life.

Science frowns on the violet ray machine

Despite their popularity, the machines didn’t fare quite as well within the medical establishment. In 1917, editors at the Journal of the American Medical Association reported that a violet ray generator certainly couldn’t treat “practically every ailment known to mankind,” as one manufacturer had claimed. Although the devices emitted a violet color, they were not in fact emitting ultraviolet light, or at least not in amounts that would be beneficial. In 1951, a Maryland district court ruled against a company named Master Appliances in a libel suit. The charge was misbranding, and the court found that the device was not an effective treatment nor capable of producing the claimed results. At the time, Master Appliances was one of the last manufacturers of violet ray machines in the United States, and the ruling effectively ended production in this country.

And yet you can still buy violet ray machines today—both the antique variety and its modern equivalent. Today’s units are mainly marketed to aestheticians or sold for home use, and some dermatologists are not ready to categorically dismiss their benefits. Although they probably won’t cure indigestion or gray hair, the high frequency can dry out the skin and ozone does kill bacteria, so the machines may help treat acne and other skin conditions. Plus, there’s the placebo effect. As with all consumer electronics for which outrageous claims are made, let the buyer beware.

Part of a continuing series looking at photographs of historical artifacts that embrace the boundless potential of technology.

An abridged version of this article appears in the October 2022 print issue.

- This 1850s Medical Device Was Said to Cure Toothache, Gangrene ... ›

- We've Been Killing Deadly Germs With UV Light for More Than a ... ›

- UV Light Might Keep the World Safe From the Coronavirus—and ... ›

- The Electric Eraser: A Surprisingly Useful Tool - IEEE Spectrum ›

Allison Marsh is a professor in Women and Gender Studies at the University of South Carolina and codirector of the university’s Ann Johnson Institute for Science, Technology & Society. She combines her interests in engineering, history, and museum objects to write the Past Forward column, which tells the story of technology through historical artifacts. Marsh is currently working on a book on the history of women in electrical engineering.