The Uber tragedy earlier this month sent a shudder throughout the autonomous vehicle industry. Some of the companies working on the technology paused testing. Nvidia was one of them.

“We suspended because there is obviously a new data point as a result of the accident,” said Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang. “As good engineers, we should simply wait to see if we can learn something from that experience. We don’t know that we would do anything different, but we should give ourselves time to see if we can learn from that incident. It won’t take long.”

Huang made that remark during a press briefing at the 2018 GPU Technology Conference (GTC). In an earlier keynote address he discussed Nvidia’s role in developing autonomous driving technology—and a new product. His inner engineer shining through, Huang rattled off numbers to make his case.

“Civilization drives about 10 trillion miles a year,” he said. “In the U.S., 770 accidents happen per 1 billion miles. [Automotive] safety work in the U.S. has reduced the number of accidents, so now you have to drive a billion miles to produce 770 accidents.”

That means, he said, “You have to ask yourself how confident you are when your fleet of 20 test cars has driven 1 million miles.”

Autonomous cars need a lot more miles under their wheels than that, he indicated, to gain enough experience under a variety of conditions so that their designers can fine-tune—and then prove—their safety. The answer, Huang said, is doing the bulk of the testing in virtual reality.

“That’s where Nvidia can shine. We know how to build VR worlds. We could have thousands of these worlds with thousands of scenarios running, with our AI car driving itself through these worlds. If something happens, it could send us an email and we can jump in and figure out what was going on.”

“We could use VR to create extreme-corner rare scenarios that are completely repeatable,” he indicated, “so engineers can debug these systems.”

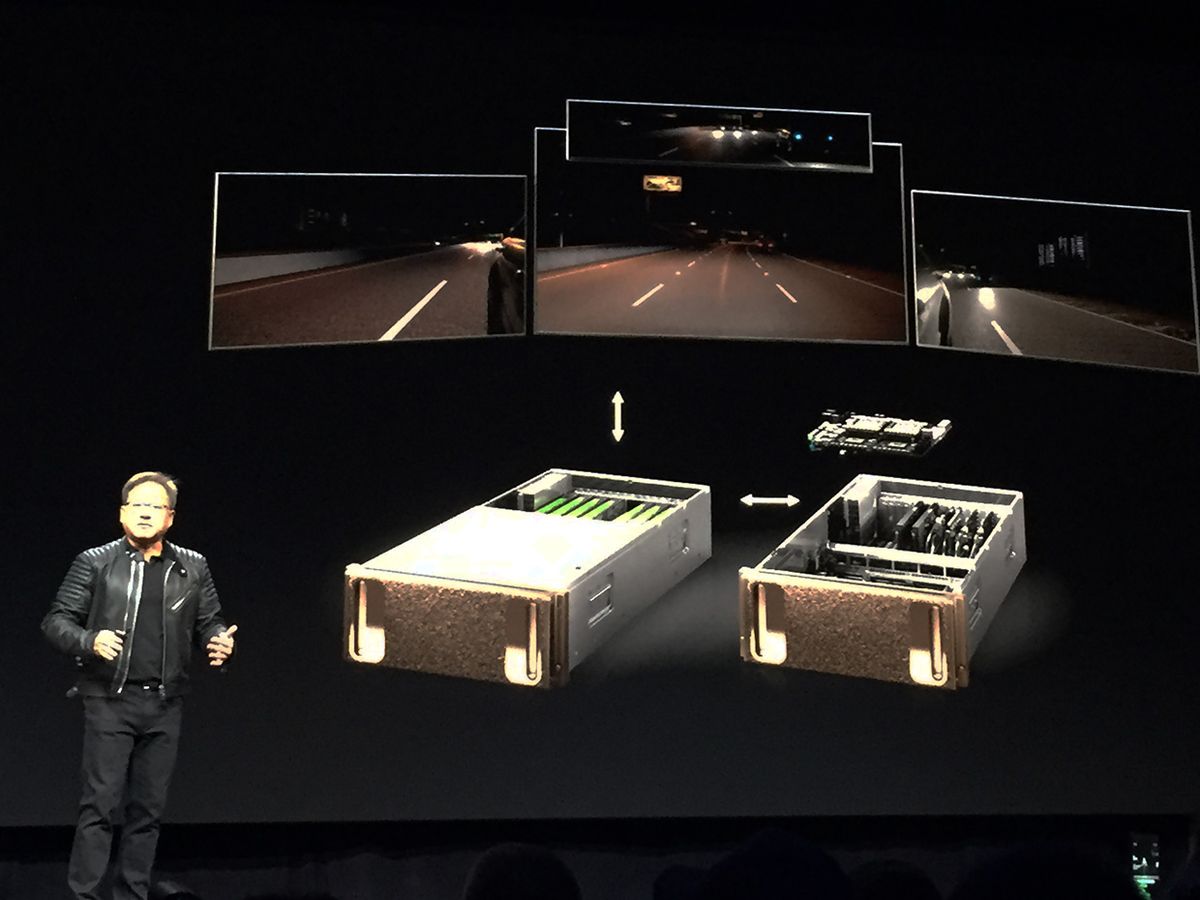

At that point Huang unveiled an Nvidia product: Drive Constellation. The system uses two servers. One simulates inputs to a car’s sensors—that is, what a car’s cameras, lidar, radar, and other sensors would pick up as it went along. This server can be adjusted to vary lighting conditions, weather conditions, and the behavior of other vehicles and pedestrians. The other server runs the same software used by the vehicle itself, processing the simulated data and reacting to it.

“Think of it as a video game,” Huang said. The input generator is the gaming PC; the other server is the person playing the game.

This, Huang said, “is how we are going to bridge the gap between actual test driving and the billions of miles we need to experience over time. With 10,000 Constellations running, we could cover 3 billion miles a year.”

Simulation alone isn’t going to make autonomous cars safe, Huang pointed out. Indeed, he said, autonomous vehicle safety “is probably the hardest computing problem the world has encountered.... [It] is the ultimate high-performance computing, deep-learning problem.”

The challenge comes from the large number and wide variety of sensors needed for autonomous driving and the need to fuse them into a supersensor, Huang said. “To do this at a high rate of speed is incredibly hard. And the computers have to operate well even when faults are detected. This entire system has not been created in totality even once.” And, he said, “as we were reminded last week, much is at stake.”

One obstacle to making autonomous vehicles safe and reliable, he indicated, is energy consumption. In electric cars, it’s all about battery life, so the more energy efficient computing systems are, the more we can put redundant systems into vehicles.

He also pointed to the “giant data problem.” Nvidia’s test cars, he said, “are collecting petabytes of data. We have 1,500 people labeling images—it’s a massive investment.”

A less obvious but still critical challenge, Huang pointed out, is documentation, so faults can be traced back if anything happens. This, too, he said, represents a gigantic investment.

Huang acknowledged that while Uber’s Arizona accident was “tragic in itself,” it’s likely to lead to product sales for Nvidia.

“I believe as a result of what happened last week,” said Huang, “the amount of investment into the development of AVs will go up. Anybody who thought they could get by without supercomputers and data collection and [a large] number of engineers” doesn’t think that anymore. “The world will be more serious about investing in development systems. For our company, from a business perspective, for the next few years it’s all development systems.”

But it’s not just about the money, he indicated. “We are developing this technology because we believe it will save lives.”

Portions of this post appear in the May 2018 print magazine in the article “Move Over, Moore’s Law: Make Way for Huang’s Law.”

Tekla S. Perry is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum. Based in Palo Alto, Calif., she's been covering the people, companies, and technology that make Silicon Valley a special place for more than 40 years. An IEEE member, she holds a bachelor's degree in journalism from Michigan State University.