Scientists have harvested energy from a guinea pig's inner ear and used it to power a small wireless transmitter. With further design work, researchers could harvest this biological battery to power implanted devices near the human ear, such as molecular sensors and drug delivery vehicles for hearing loss and other disorders, according to a study to be published today in Nature Biotechnology.

It has been known for decades that the inner ear contains this biological battery, but until now, no one has harvested it. The authors of the paper, led by Anantha Chandrakasan at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Konstantina Stankovic at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, succeeded without damaging the guinea pigs' hearing.

The inner ear's biological battery is located in a spiral-shaped auditory region called the cochlea. The electric potential in this region arises from the electrical difference between two different chambers in the cochlea, which contain charged particles such as potassium and chloride ions. A nearby specialized structure known as the stria vascularis transports the ions through its unique arrangement of electrogenic ion pumps, generating an electrochemical potential known as the endocochlear potential.

At 70-100 mV, the electrochemical potential of the inner ear is the highest in the mammalian body. But it's still a very small amount of energy, and only a fraction of it can be extracted without disrupting hearing. To address this challenge, the researchers chose to power a specially designed chip equipped with an ultralow-power radio transmitter.

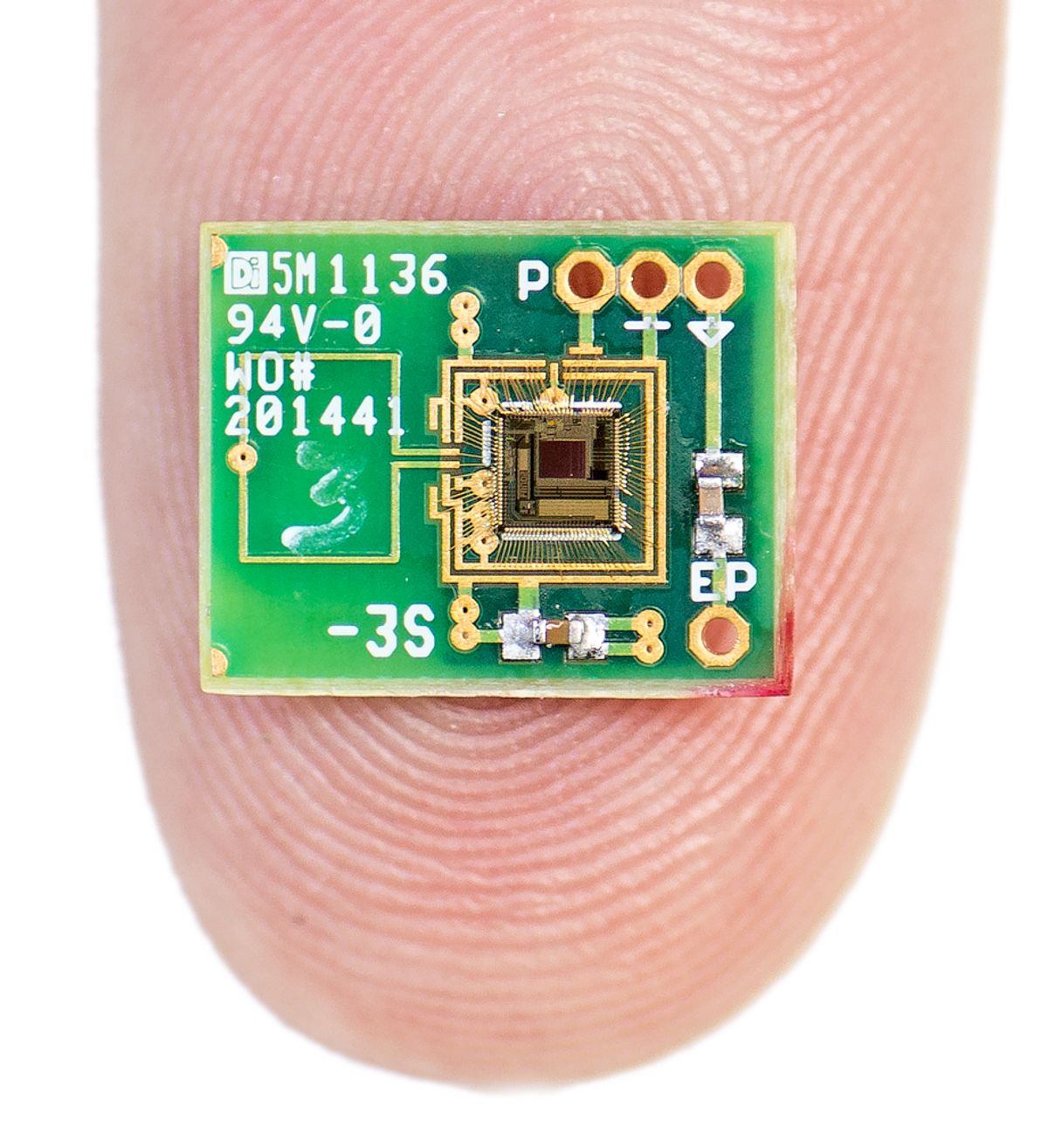

In the experiments, the researchers implanted electrodes in the cochlea of anesthetized guinea pigs. The electrodes were connected to the chip, which was located outside the animals' ears. (It is small enough to fit in a human ear.) The chip included power-conversion circuitry that gradually builds up charge in a capacitor. To kick-start the control circuit, the researchers applied a one-time burst of radio waves. The device wirelessly transmitted measurements of the endocochlear potential to an external receiver. About 1 nW of power was extracted for up to 5 hours—long enough to enable the 2.4 GHz radio to transmit measurements every 40-360 seconds.

Harvesting energy from the human ear to power small electronic devices could be a huge breakthrough for people grappling with hearing loss and other disorders. Implantable electronics usually require large energy reservoirs to operate reliably over long periods of time. But human anatomy limits the size of implantable batteries, and often requires surgical re-implantation or cumbersome external wireless power sources. Harvesting enough energy from the body's own energy sources is a way to extend implant life, and maybe even allow it to operate autonomously, the authors report.

Images: Patrick P. Mercier

Emily Waltz is a features editor at Spectrum covering power and energy. Prior to joining the staff in January 2024, Emily spent 18 years as a freelance journalist covering biotechnology, primarily for the Nature research journals and Spectrum. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Discover, Outside, and the New York Times. Emily has a master's degree from Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and an undergraduate degree from Vanderbilt University. With every word she writes, Emily strives to say something true and useful. She posts on Twitter/X @EmWaltz and her portfolio can be found on her website.