Global policy efforts to boost fuel economy are progressively electrifying the automobile and expanding technology options to cut greenhouse gas emissions. One of the most exciting recent developments is, however, at risk of failure in the United States: a new generation of “mild hybrid” technology that could be undercut by President Donald Trump’s attempts to stall U.S. climate policy.

In March, Trump ordered the Environmental Protection Agency to rethink fuel economy mandates set under President Obama. Those mandates require cars and light trucks sold in the United States between 2022 and 2025 to deliver an average of 6.5 liters per 100 kilometers (36 miles per gallon) in real-world driving— a 40 percent efficiency improvement over the average vehicle sold in 2016.

Mild hybrids rely on batteries, motors, and other components that are cheaper than the ones used in full hybrids, such as Chrysler’s new Pacifica hybrid minivan [see “2017 Top Ten Tech Cars,” IEEE Spectrum, April 2017]. By providing more targeted support to a vehicle’s internal combustion engine, mild hybrids are both cheaper to produce and more cost-effective at cutting carbon dioxide emissions than full hybrids, according to vehicle experts. “You get about 70 percent of the fuel economy benefit of a full strong-hybrid system but at about 30 percent of the cost,” says Sam Abuelsamid, a Detroit-based senior research analyst with energy consultancy Navigant Research. For the U.S. market, mild-hybrid tech would enable popular pickup trucks and SUVs to make do with cheaper four-cylinder engines instead of V-6s.

The technology itself is getting cheaper as lower-voltage designs replace their 100- to 120-volt predecessors. Today’s mild-hybrid standard is 48 volts, which allows for lighter batteries with fewer cells and requires far less electrocution shielding.

Most mild hybrids employ a motor-generator that absorbs braking energy to charge a lithium battery and then returns that energy to the engine’s crankshaft during acceleration. An example is the electrified Silverado pickup that General Motors began offering in California last year and expanded in April to Hawaii, Oregon, Texas, and Washington. The technology cuts fuel use in city driving by up to 13 percent: It helps keep half of the V-8 engine’s cylinders deactivated and lets it turn off at red lights.

Daimler plans to make 48-V motor-generators ubiquitous in Mercedes-Benz vehicles, starting with an electrically boosted S-Class sedan launching later this year. Besides its motor-generator, the mild hybrid’s electrical system will supercharge the turbo engine, eliminating the traditional exhaust-driven turbo’s torque lag.

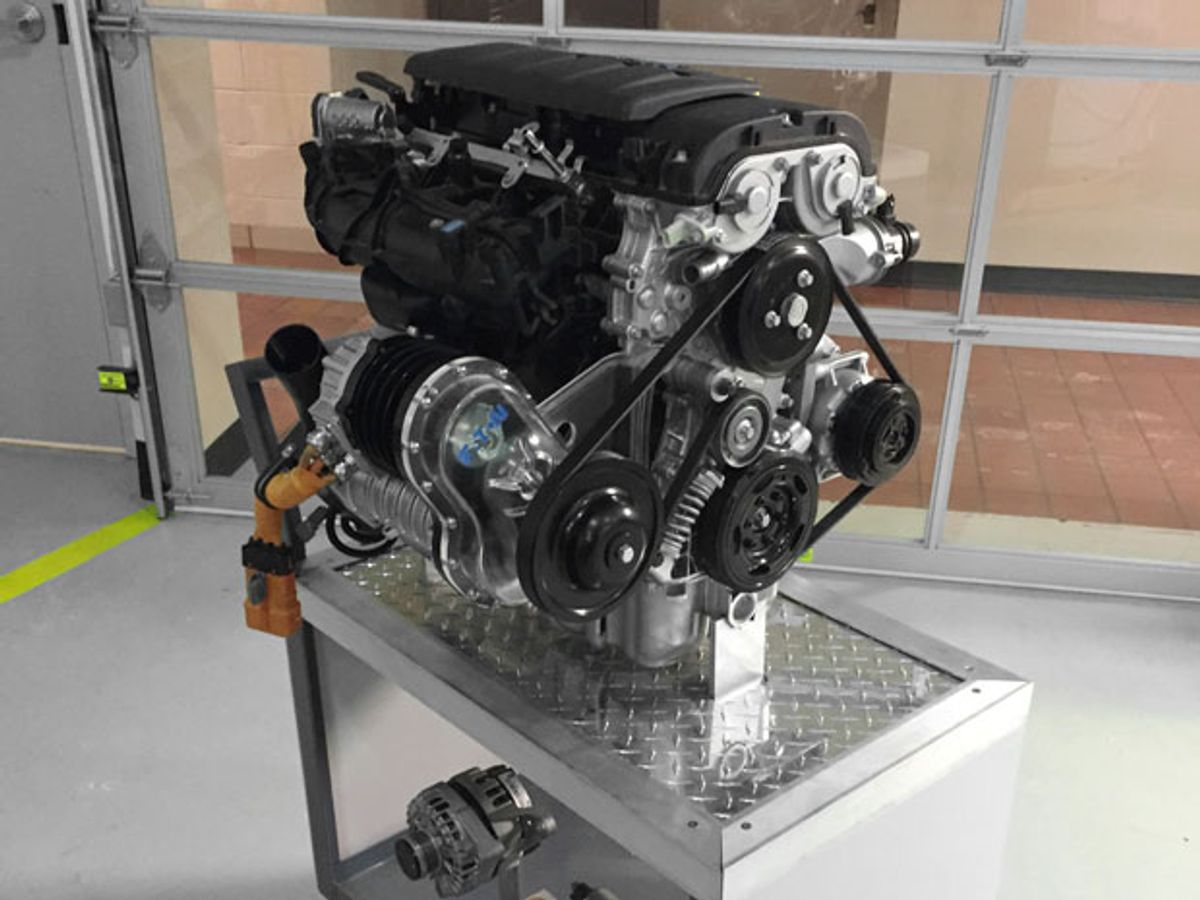

Top-tier suppliers, meanwhile, have pushed the mild-hybrid concept further. Both Ohio-based Eaton and Ricardo, based in the United Kingdom, are testing mild hybrids that use engine exhaust to generate electricity, adding to the regenerative braking that charges the hybrid battery. Mihai Dorobantu, technology planning director for Eaton’s vehicle group, says the company is showing off a demonstrator vehicle to automakers at its proving grounds in Marshall, Mich.

The challenge to selling such efficiency-boosting technology is that it increases a vehicle’s sticker price. GM charges a US $500 premium on its hybrid Silverados. With gas prices in the United States currently averaging a low $2.30, the added system will take seven years to pay for itself. Most consumers—and the automakers serving them—do not make such investments unless mandates force their hands.

Mild hybrids were projected to make up 18 percent of cars and light trucks sold in 2025 in the United States, according to a joint analysis issued last year by the EPA, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, and California regulators. That number was 2.5 times as large as the combined share projected for full hybrids and battery EVs.

That projection looks optimistic under the Trump administration, according to Abuelsamid. He says Trump’s EPA may retain Obama’s standards but make them more flexible and lower penalties—in practice, rendering the rules voluntary. Abuelsamid says he had expected significant mild-hybrid growth from 2019 in the United States, but that could be delayed by four to five years.

Delay could hurt companies like Eaton that spent big on development. “Weakened or delayed standards would ultimately leave technology on the table,” says Nic Lutsey, program director at the Washington, D.C.–based International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). A recent survey of suppliers by Ricardo found that 70 percent favored maintaining the EPA’s rules. “They’ve made…those investments, and now they want to make sure there’s still a market for them,” Lutsey says.

That said, suppliers still have tougher mandates in markets such as China and Europe to rely on. European regulations, for example, limit gasoline-fueled cars to just 4.1 L/100 km (57 mpg) from 2021, and will require a further 17 to 28 percent reduction from 2025. Of the 5.6 million 48-V electric turbochargers that Navigant projects will be installed worldwide in 2025, 85 percent are for Europe and Asia.

As Dorobantu puts it, the “quest for higher and higher efficiency in vehicles” are “macro trends” that are independent of the EPA’s standards. “It is those macro trends that are guiding our investments.”