Phoenix Motorcars' battery-powered pickup truck seems, at first glance, like any other electric vehicle. But it has a trick up its sleeve: the truck's hefty 35-kilowatt-hour battery can recharge in a record 10 minutes flat--a feat that would ruin or even ignite most EV batteries.

Phoenix, a start-up in Rancho Cucamonga, Calif., bets that rapid charging will eventually make battery EVs more popular with consumers by eliminating the threat of being stranded with a dead battery. But Phoenix is also counting on a more immediate payoff: the company may be eligible to cash in on California's ambitious and controversial zero-emissions vehicle mandate. The ZEV directive requires car manufacturers to market ultraclean and emissions-free vehicles or buy credits earned by others making such vehicles--credits that could translate into tens of thousands of dollars in extra income per vehicle for Phoenix.

”We're using the ZEV mandate as a tool to finance and progress our company,” says Bryon Bliss, Phoenix's vice president of sales and marketing.

Phoenix's bid for extra credits is just one example of what has become a scramble to exploit California's ZEV incentives. Thanks to the heft of the state's huge automotive market--plus that of the many other U.S. states that have signed on to the ZEV program--the mandate has driven gasoline-electric hybrids onto car lots across the country. Now battery EV start-ups, major automakers, hydrogen fuel-cell developers, and coalitions promoting plugâ''ins (hybrid EVs that recharge on the power grid overnight) are lobbying the California Air Resources Board (CARB) to favor their respective automotive visions. This winter, the board plans to consider adjustments to the ratio of credits earned by various ZEV technologies, a ratio that currently favors fuel cells and offers relatively little help for hybrids.

”Changing that ratio has a lot of implications,” says Daniel Sperling, director of the University of California, Davis, Institute of Transportation Studies--a longtime observer of the ZEV program and a member of CARB. Sperling says he is especially concerned about the impact on fuel-cell R&D if CARB reduces the generous credits for fuel-cell vehicles. ”Automakers might abandon their fuel-cell programs,” he warns.

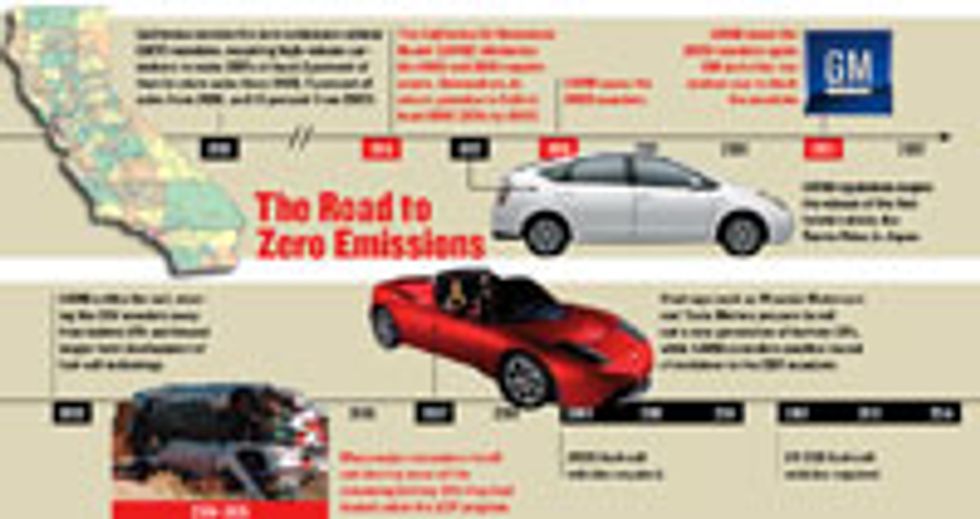

California legislators created the ZEV mandate back in 1990 after General Motors vowed to mass-produce its sporty EV1, a battery-powered two-seater. The mandate consisted of just a few sentences, stating that major manufacturers' California sales must include at least 2 percent ZEVs in the model years 1998 through 2000, 5 percent ZEVs in 2001 and 2002, and 10 percent ZEVs in 2003 and subsequent years. Increasing volume was supposed to drive improvements in the performance of electric drivetrains and slash their cost.

In practice, however, battery development lagged. So CARB repeatedly trimmed the quotas for ZEVs, allowing manufacturers to build a larger number of ultraclean combustion vehicles, which the board oxymoronically termed partial zero-emissions vehicles. These include cars with advanced emissions controls, natural gas–powered vehicles, and gasoline-electric hybrids. Each category qualifies for a different number of credits toward the manufacturers' ZEV quotas.

More than half a million cars have been sold under the ZEV program. And the hybrid vehicles sweeping the market today, the Toyota Prius in particular, have their roots in carmakers' attempts to comply with the mandate. What is missing, however, are the thousands of emissions-free vehicles originally promised.

The regulation's downfall came in 2003 when the mandate, set to come into full force, was instead derailed by a GM-led lawsuit. The industry litigants argued that CARB's incentives for gasoline-sipping hybrids showed the ZEV mandate was regulating fuel efficiency, a power granted to the federal government. The board settled the suit by giving automakers a way out. Instead of making thousands of battery EVs each, automakers could embark on an industry-wide effort to commercialize fuel-cell vehicles, beginning with the demonstration of just 250 fuel-cell cars by 2008, with more to follow.

The Big 6--DaimlerChrysler, Ford, GM, Honda, Nissan, and Toyota--lost no time getting to work on fuel cells, and they are on schedule to produce the fuel-cell cars promised for next year.

But with the emphasis on fuel cells, carmakers were free to give up on their battery EVs, and all but Toyota did so. By 2003 the Big 6 had built about 4400 battery EVs under the ZEV program. Most were recalled and crushed (in Honda's case, shredded) after the court settlement.

Accelerate forward from 2003 to today and it's a brave new world. Hybrids are going mainstream, major automakers are once again engineering battery EVs, and start-ups such as Tesla Motors and Phoenix are actually bringing them to market. Even GM, vilified in the 2006 documentary Who Killed the Electric Car? for crushing its EV1s, says electric drive is the future. ”We need to do everything we can to rid ourselves from complete dependence on oil as our single source for automotive transportation,” says Dave Barthmuss, GM's environmental spokesman in California.

The question, yet again, is whether the ZEV mandate can help.

Automakers want more time, and more credits, for fuel-cell technology. The vehicles just aren't ready: according to an independent review released by CARB in April, fuel cells remain 20 times as expensive as combustion engines and last as little as three years, hydrogen storage tanks are inadequate, and hydrogen fuel stations are nonexistent. Carmakers propose delivering 2500 to 5000 fuel-cell vehicles through 2014, one-fifth to one-tenth of what they promised in the 2003 court settlement. And they want to continue receiving extra ZEV credits for every fuel-cell vehicle built. Right now each hydrogen vehicle earns four times as many credits as a battery EV, but that advantage is slated to narrow after 2009.

Proponents of battery EVs, on the other hand, want CARB to give them parity with fuel-cell cars. Technology is an issue for battery EV makers, too. CARB's April review concluded that battery EVs comparable to today's internal combustion vehicles in range and price would not be ready for even small-scale commercialization before 2015. But battery EV proponents say that thanks to today's climate--economic, political, and atmospheric--some consumers are ready to trade range for a car that costs less to run and produces less pollution. CARB Chairwoman Mary Nichols agrees. ”People are willing to take a chance on a car that doesn't necessarily do everything the old Taurus used to do,” she says.

Nichols says she is especially bullish about plug-in hybrids--which could be good news for that technology's backers if it translates into new policy. At present, CARB offers to plug-ins less than one quarter of the credits it gives to battery EVs, mostly because there is no guarantee that drivers will plug them in.

Then there's Phoenix, a battery EV developer that likes the ZEV mandate's favoritism for fuel cells. Why? Because the extra credits earned by fuel-cell manufacturers are the same credits Phoenix has requested for its rapid-charging truck. In 2003, when CARB shifted its emphasis to fuel cells, it did so by creating a new category of ZEVs, awarding the extra credits to any ZEV that travels 160 kilometers and refuels in 10 minutes or less.

When CARB wrote those rules, it assumed that only fuel cells would qualify, but Phoenix found a battery capable of the trick: a lithium titanate cell made by Altair Nanotechnologies of Reno, Nev. Charging a lithium battery generally means shifting lithium ions from a lithium metal oxide cathode into a graphite anode. Do that with too much force and lithium ions form a layer of highly energetic (and flammable) lithium metal on the graphite cathode. Altair Nano's battery replaces the graphite with a titanium oxide anode that is much less susceptible to such plating, so the battery can be charged rapidly at very high power. [See ”Lithium Batteries Take to the Road,” IEEE Spectrum, September.]

Alan Gotcher, Altair Nano's chief executive, says bonus credits, which were still pending at press time, would be a just reward. ”That's what the program was designed for, to bring some innovation to solve a very tough problem,” he says.

Others see Phoenix's potential windfall as a distortion of the mandate. J.B. Straubel, chief technical officer with Tesla, in San Carlos, Calif., is one of many critics. Straubel questions the practicality of rapid charging, because it requires megawatt power levels hard to find beyond electrical substations. And he says rapid charging is merely a loophole in the regulation. ”That can change at the stroke of a pen, and I think it will,” he says.

It would hardly be the first time a ZEV rule-change upended entrepreneurs. The board's rollbacks in the 1990s burned start-ups of that era. In Straubel's judgment, the ever-shifting targets diminish the program's impact. He and others expect the auto industry to wiggle out of CARB's quotas once again.

While Straubel stops short of dismissing the program entirely, other critics are less forgiving. ”It's a political regulation driving impractical solutions. It's not really relevant to the real world,” says EV battery expert Menahem Anderman, president of Total Battery Consulting, in Oregon House, Calif. Anderman argues that California should shelve the program in favor of broader measures now in the works, including tough fuel-economy standards legislated in 2002 and a cap-and-trade program for greenhouse gases. These measures would raise the cost of gasoline and gasoline-burning cars, leveling the field somewhat for electric-drive vehicles, he says.

Sperling and other energy policy experts say such broad measures would accelerate the adoption of existing alternatives such as plug-in hybrids, but they could prove insufficient to drive the immense investments needed for new technologies. ”The challenge for policy is to somehow address the start-up barriers,” Sperling says. He predicts that, without the ZEV mandate, short-term considerations determine what automakers offer the market. ”Companies are going just to pick the easy way,” he says, ”and the easy way is not necessarily in the public's interest.”

Click here to see "The Road to Zero Emissions"