The Quantified Olympian: Wearables for Elite Athletes

Baseball pitchers, cyclists, and other competitors seek an edge with new gadgets

“I definitely see them as becoming part of everyday training,” says Marko Yrjovuori, a biomechanics specialist who trains the Los Angeles Lakers basketball team. Here are some state-of-the-art systems that are changing the game for elite athletes, including a few within reach of dedicated amateurs.

Illustration: Bryan Christie Design

Readiband

What it is: This electronic wristband measures sleep quality and quantity, which can help predict a player’s reaction time for the next day. Coaches can use an associated online tool to monitor the sleep patterns and fatigue of professional athletes.

How it works: The band’s accelerometer senses tiny movements of the wearer’s wrist, which reveal whether the wearer is asleep or awake. To predict fatigue, the results are fed through the SAFTE (Sleep, Activity, Fatigue, Task, and Effectiveness) model, which was developed by the U.S. Army. An “effectiveness score” rates the quality of the wearer’s slumber.

Who’s using it: Vancouver Canucks, Seattle Sounders, and Dallas Mavericks

Price: US $22,800 per year for 20 Readibands, including analytics software (individual wristbands are not sold)

Illustration: Bryan Christie Design

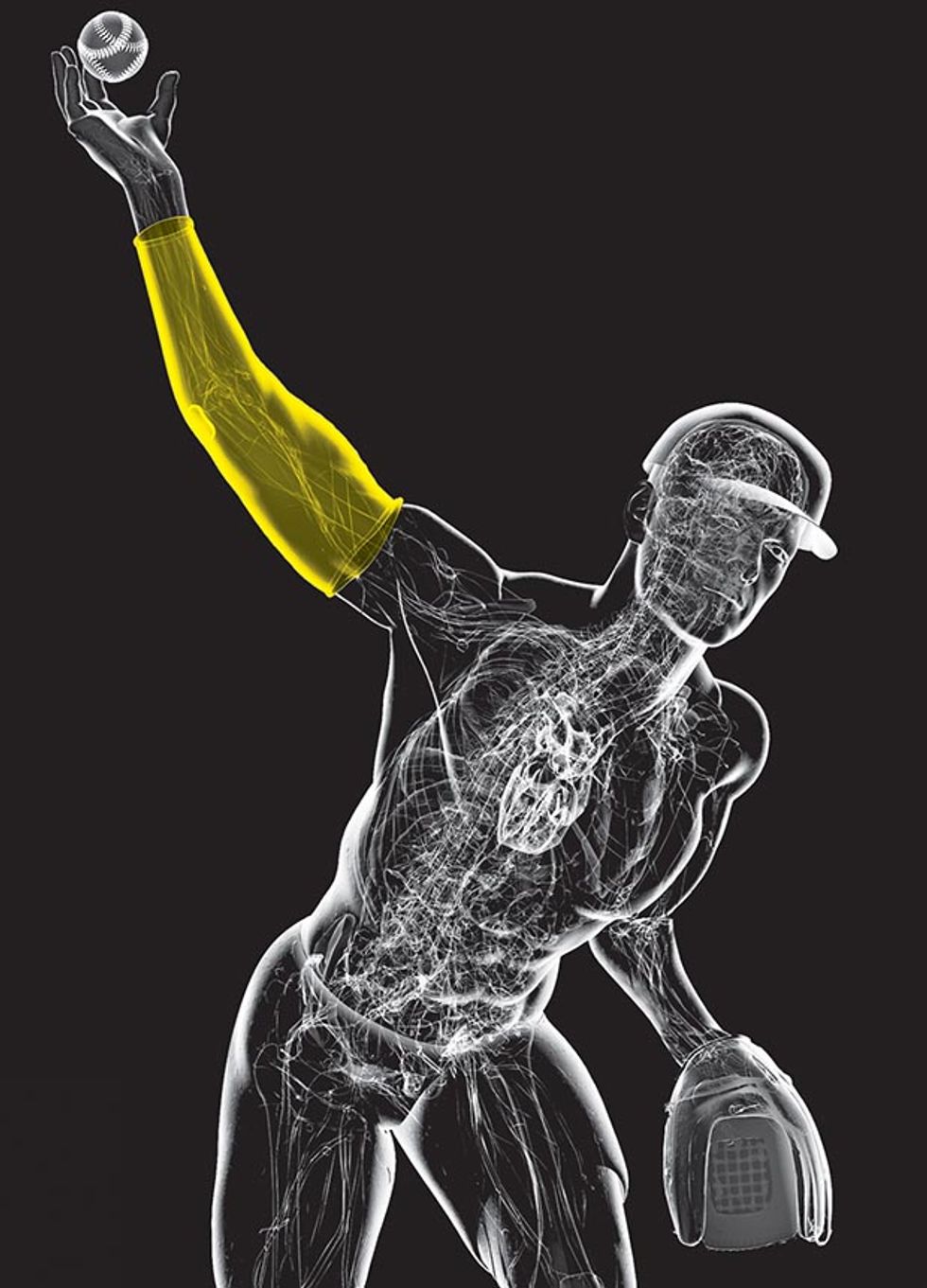

Motus Sleeve

What it is: A compression sleeve with sensors tracks a baseball player’s throwing motions. Pitchers who use the sleeves to correct their technique may be able to prevent ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) injuries, which have resulted in an epidemic of reconstructive procedures known as Tommy John surgeries. Previously, quantifying ballplayers’ throwing motions required motion-capture imaging.

How it works: The sleeve tracks arm movements with accelerometers and gyroscopes and sends data via Bluetooth to a smartphone. Based on an estimate of the player’s arm motions and basic biomechanical principles, the Motus app calculates elbow torque—the stress a pitcher puts on his UCL. It also tracks metrics such as arm speed, maximum shoulder rotation, and elbow height at ball release.

Who’s using it: Pitchers with more than two dozen professional baseball teams during spring training this year

Price: US $150

Illustration: Bryan Christie Design

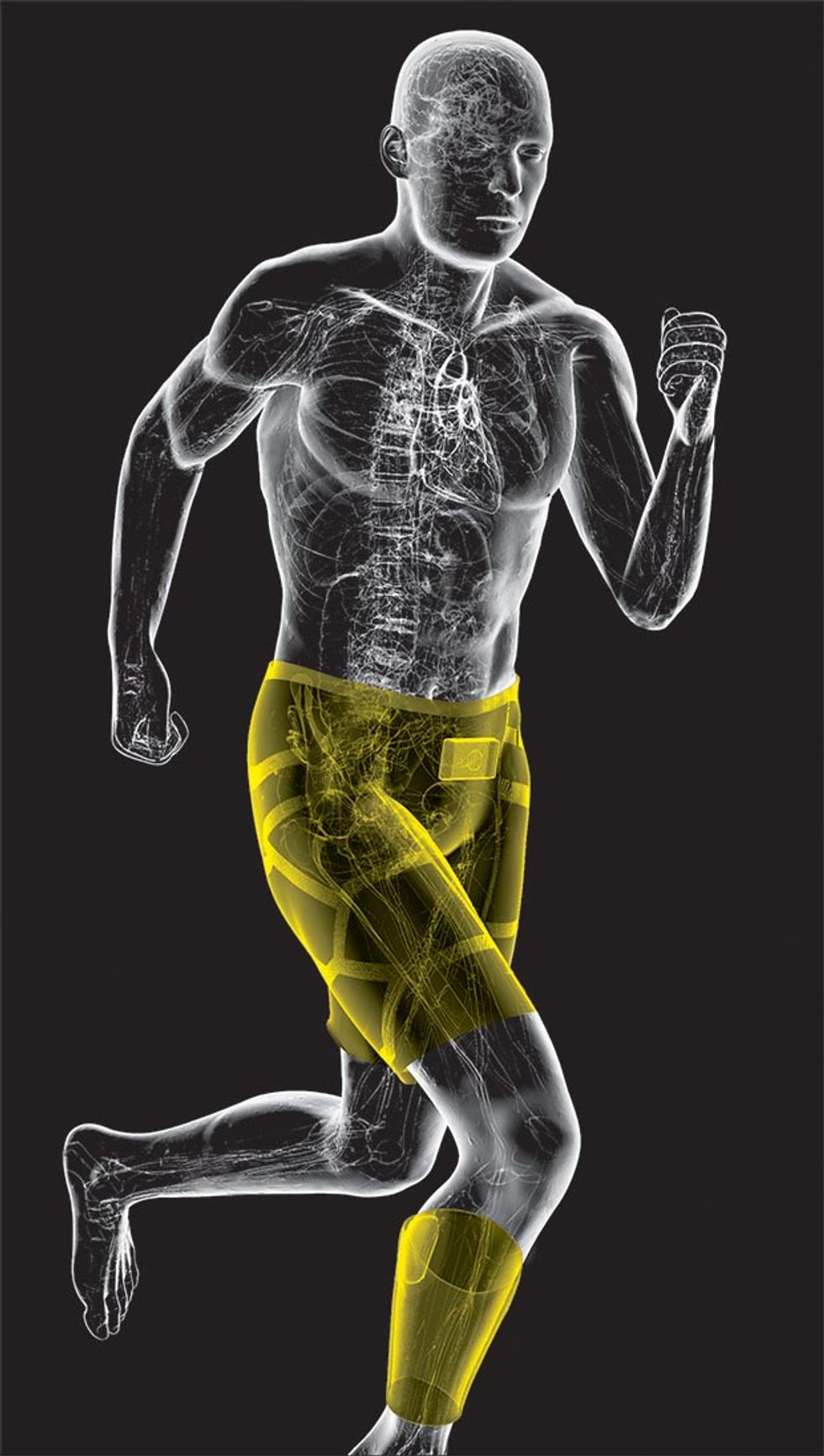

Myontec Mbody Pro

What it is: Compression shorts with sensors measure muscle imbalances in the legs. The garment can determine, for example, whether athletes are favoring one leg or are using their quadriceps disproportionately compared with their hamstrings. The feedback can help athletes improve their technique and possibly forestall cramps or injuries.

How it works: The shorts combine electromyography (EMG) measurements of muscle activity with accelerometer and heart-rate data. The high-end version, Mbody Pro, provides a more detailed analysis of EMG data than the consumer versions, Mbody Bike&Run and Mbody AllSports.

Who’s using it: Los Angeles Lakers, Pittsburgh Penguins, professional boxers, Olympic snowboarders and ice skaters, and more than 20 sports institutes and training centers around the world

Price: €4,000–€6,800 (€770 for the consumer-version starter kit)

BSX Insight

What it is: A compression sleeve worn on the calf measures lactate threshold—the level of exercise intensity above which lactic acid builds up in the bloodstream, causing discomfort and forcing the athlete to slow down. Normally, monitoring lactate threshold requires multiple finger-prick blood samples, which must be sent to a lab. This noninvasive sensor, however, can be worn while working out.

How it works: The device uses near-infrared spectroscopy to estimate lactic-acid concentration. Lights of different wavelengths shine through arteries in the calf, and sensors measure the reflections to reveal changes in blood oxygenation and other parameters.

Who’s using it: Many professional cyclists, runners, and triathletes, as well as a British soccer team and an NBA team

Price: US $420 (multisport version)

Illustration: Bryan Christie Design OptimEye S5

What it is: This device’s sensors precisely record a player’s movement on the field or court. The device, which sits over the upper back inside a compression garment, monitors acceleration, deceleration, change of direction, jump height, and distance traveled, among other metrics. Coaches use the data to keep tabs on how hard players are working and to prevent injuries resulting from overtraining.

How it works: Accelerometers, magnetometers, gyroscopes, and a GPS receiver record as many as 100 data points per second. Algorithms determine what the athlete is doing based on the software’s sport- and position-specific analytics. The data is accessible in real time on the sidelines through a wireless link.

Who’s using it: Nearly half of the NFL, a third of the NBA, more than 100 NCAA teams, half the English Premier League, and dozens of other professional hockey, soccer, rugby, and rowing teams around the world

Price: About US $175 per athlete per month, depending on the number of devices purchased

This article originally appeared in print as “The Quantified Olympian.”

About the Author

Emily Waltz is a freelance journalist based in Nashville. She was well motivated to survey some electronic aids that athletes are using to guard against injury and boost performance. “I’ve played tennis since I was 5, and by the time I was a senior on my high school team, the spine-bending motion of my serve had done a number on my lower back,” says Waltz. “Keeping an eye on a kid’s mechanics using wearable sensors might help coaches and parents prevent such injuries.”

Illustration: Bryan Christie Design

Illustration: Bryan Christie Design Illustration: Bryan Christie Design

Illustration: Bryan Christie Design Illustration: Bryan Christie Design

Illustration: Bryan Christie Design