Part of the mythology of the early Internet was that it was going to make the world a better place by giving voice to the masses and leveling playing fields. Light was the metaphor of choice. For example, Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak once said that “when the Internet first came, I thought it was just the beacon of freedom.”

You can easily make a case for how much “brighter” the world is now, thanks to ubiquitous connectivity shining a light on misbehavior and malfeasance, but the Internet has a dark side as well.

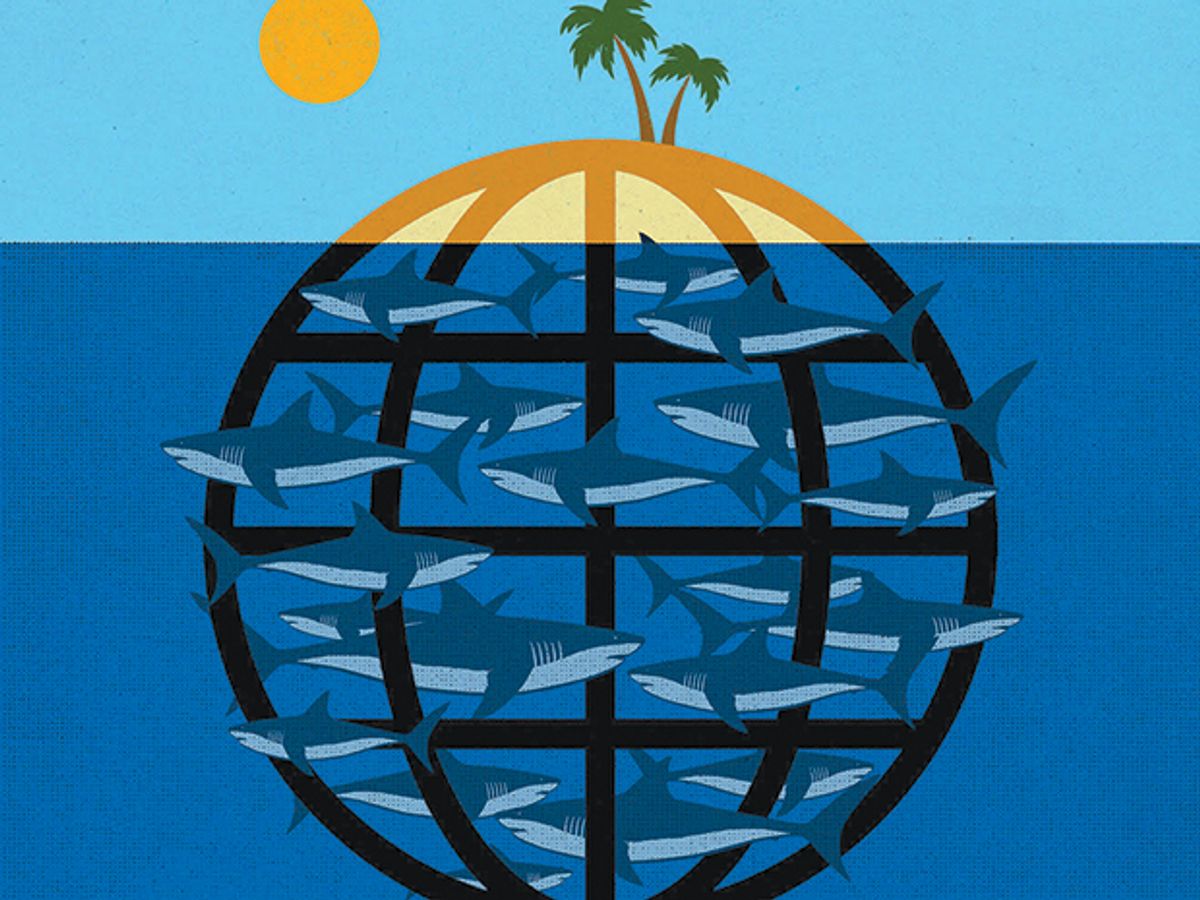

For example, when you enter a search term into Google and it spits out the results, you might think that the search engine spent those few milliseconds querying the entire Web. Nope, not even close. What Google indexes is a fraction of all the available Web, perhaps just 4 percent of the total, by some estimates. That indexed soupçon is called the surface Web, or sometimes the visible Web. What about the other 96 percent? That nonsearchable content is called the deep Web, dark Web, or sometimes the invisible Web. A related idea is dark social, those online social interactions that are not public and cannot be directly tracked or traced (such as text messages and emails).

Most of this hidden Web is obscured either because it resides within databases that are inaccessible to search crawlers (because they require that information be entered into an HTML form), or because those crawlers don’t have permission to access certain types of data (such as the personal info that people store within the cloud).

But a significant subset of the hidden Web is the online equivalent of caves, lairs, and dungeons where hackers, criminals, and trolls gather. I speak now of the aforementioned dark Web, the collection of websites where miscreants and malefactors go to buy or sell narcotics, weapons, and stolen goods (these are known as dark markets), where the desperate and the desperadoes hire hitmen and arsonists, and where trolls and dark-side hackers gather covertly in forums and chat rooms. This so-called darknet is hidden from view not because an HTML form is in the way but because it requires special tools to get there at all. The most common of these is Tor, a worldwide network of relays run by volunteers that anonymizes and encrypts traffic to the black Web’s typical .onion URLs (Tor is short for The Onion Router).

The darknet seems like a place populated only by the lawless and the anarchic, but does it have anything to offer the rest of us? Consider, for example, that the Tor network itself has also received considerable U.S. government funding, in part to protect democratic movements in authoritarian regimes. And in 2014, the broadcaster Alan Pearce released a Kindle book called Deep Web for Journalists, with the aim of showing reporters how to keep themselves and their sources safe on the Internet by using the techniques of countersurveillance, including secure communications and online anonymity. (I should note here that these days people routinely conflate the terms deep Web and dark Web.) Some reporters are practicing the techniques of secure journalism, which include such darknet stalwarts as secure messaging, virtual private networking, and device encryption.

But there’s a counterargument here, which is that anonymizing your online activity serves only to legitimize surveillance and will lead only to more powerful snooping techniques. Instead, we should be trying to get governments to stop spying on their citizens. Rather than wielding powerful anonymizing tools, World Wide Web inventor Sir Tim Berners-Lee says we should be “going to protest so the world outside becomes one where you don’t need to cheat to get around this problem.” Let there be light.

This article appears in the October 2017 print issue as “The Dark Dialect.”

Paul McFedries is a technical and language writer with more than 40 books to his credit. He also runs Word Spy, a Web site and mailing list that tracks new words and phrases.