THE INSTITUTEThis month The Institute is focusing on how technology is transforming the garment industry. The Jacquard Loom was the first loom that automatically created complex textile patterns. This led to the mass production of cloth with intricate designs.

Joseph Marie Charles Jacquard of France was born into a family of weavers in 1752. He received no formal schooling but tinkered with ways to improve the mechanical textile looms of the day.

At that time, two people were needed on each loom. A skilled weaver and an assistant, or draw boy, chose by hand which warps (the lengthwise threads held under tension on the loom) to pull up so the weft (the thread inserted at right angles) could be pulled through the warps to create a pattern.

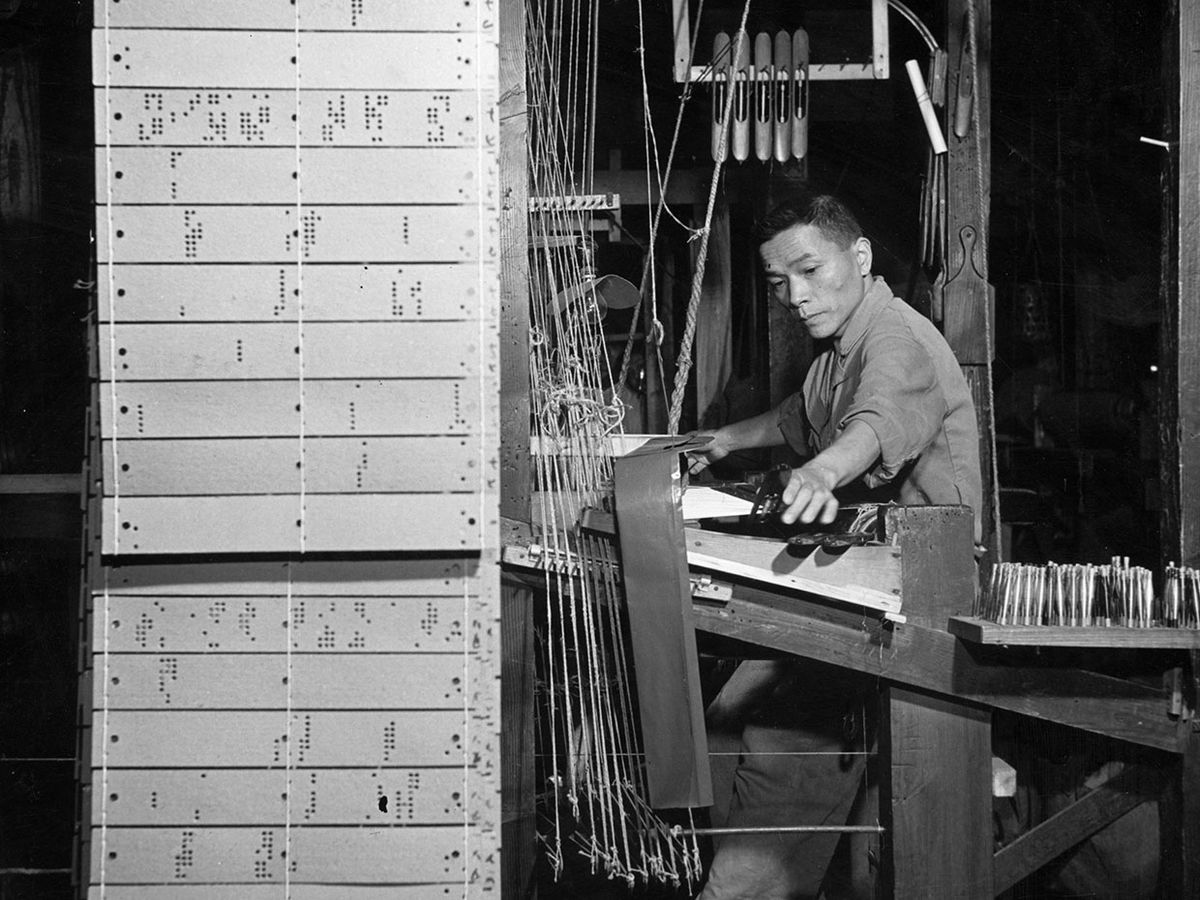

At an industrial exhibition in Paris in 1801, Jacquard demonstrated something truly remarkable: a loom in which a series of cards with punched holes (one card for each row of the design) automatically created complex textile patterns. The draw boy was no longer needed. Patterns that had been painstaking to produce and prone to error could now be mass-produced quickly and flawlessly, once programmed and punched on the cards.

The government of France soon nationalized the loom (or considered it government property) and compensated Jacquard with a pension to support him while he continued to innovate. He also was paid a royalty for each machine sold. It took Jacquard several more years to perfect the device and make it commercially successful.

The social and psychological impact of a machine that could replace human labor was immense.

HOW IT WORKED

Jacquard did not invent a whole new loom but a head that attaches to the loom and allows the weaving machine to create intricate patterns. Thus, any loom that uses the attachment is called a Jacquardloom.

The state-of the art loom at that time was one in which the harnesses holding the threads were raised or lowered by foot pedals on a treadle, leaving the weaver free to operate the machine with his hands. The Jacquard loom, in contrast, was controlled by a chain of punch cards laced together in a sequence. Multiple rows of holes were punched on each card, with one complete card corresponding to one row of the design. Chains of cards allowed sequences of any length to be constructed, not limited by the cards’ size.

Each hole position in the card corresponded to a hook, which could either be raised or lowered depending on whether the hole was punched. The hook raised or lowered the harness that carried and guided the thread. The sequence of raised and lowered threads created the pattern. A hook could be attached to a number of threads to create a continuous, intricate design.

FIERCE OPPOSITION

Already in the late 18th century, workers throughout Europe were upset with the increasing mechanization of their trades. Jacquard’s loom was fiercely opposed by silk-weavers in Paris who rightly saw it would put many of them out of work. In England, where an anti-industry workers movement was already well developed, news of the Jacquard loom fostered momentum for the Luddite movement, whose textile workers protested the new technology. Although the French looms did not arrive in England until the early 1820s, news of their existence helped intensify violent protests. People smashed the machines and killed textile mill owners; the authorities violently suppressed the protests. To this day, people who resist new technology are called Luddites.

But the Jacquard loom was too good to be ignored. Ultimately, it became standard throughout the industrializing world for weaving luxury fabrics, replaced by the dobby loom in the 1840s. In a dobby, a chain of bars with pegs, rather than foot pedals, is used to select and move the harness. Even then, parts of Jacquard’s control system could be adapted to the dobby loom.

A LONG LEGACY

Perhaps what is most interesting about the Jacquard loom was its afterlife. When computer pioneer Charles Babbage, a British mathematician, envisioned an “analytical engine” in 1837 that would essentially become the first general-purpose computer, he decided that the computer’s input would be stored on punch cards, modeled after Jacquard’s system. Although Babbage never built his engine, he and his work were well known to the mathematics community and eventually influenced the field that came to be computer science.

In the mid-1880s, the U.S. Census Bureau began to experiment with ways to automate the way it was assessing the population of the United States and processing the answers to the questions survey takers asked each household. The data from the 1880 census was overwhelming; it took eight years to compile and process. Engineer Herman Hollerith, who was on the bureau’s technical staff, felt he could improve the process. He got busy and, in 1884, filed a patent for an electromechanical device that rapidly read information encoded by punching holes on a paper tape or a set of cards. In 1889 Hollerith’s newly formed Tabulating Machine Co. was chosen to process the 1890 census. The company was decidedly successful; data from the 1890 census was compiled in only one year. The 1890 population of the United States was put at 62,947,714 people.

Apparently, Hollerith based his concept on the Jacquard loom. Historians disagree, however, as to whether he also was influenced by Babbage’s work.

The Tabulating Machine Co. eventually became IBM. (Some IEEE members undoubtedly remember using IBM punch cards into the 1970s.)

Thus, the computer industry—which became a field of cutting-edge innovation—was affected by at least two streams of influence from the Jacquard loom. It is only fitting and fair that computing is now generating innovation in the textile industry with such creations as wearables, 3-D printed clothing, and digital industrial knitting machines. Before even the telegraph, innovation in textile technology was one of the “engines” (along with steam power and iron production) that drove the Industrial Revolution.

Michael Geselowitz is senior director of the IEEE History Center, which is funded by donations to the IEEE Foundation.