More than 100 COVID-19 patients at a hospital in Beijing are receiving injections of mesenchymal stem cells to help them fend off the disease. The experimental treatment is part of an ongoing clinical trial, which coordinators say has shown early promise in alleviating COVID-19 symptoms.

However, other experts criticize the trial’s design and caution that there’s not sufficient evidence to show that the treatment works for COVID-19. They say other treatments have far greater potential than stem cells in aiding patients during the pandemic.

Researchers have so far reported results from only seven patients treated with stem cells at Beijing You’an Hospital. Each patient suffered from COVID-19 symptoms including fevers and difficulty breathing. They each received a single infusion of mesenchymal stem cells sometime between 23 January and 16 February. A few days later, investigators say, all symptoms disappeared in all seven patients. They reported no side effects.

The team published those results in the journal Aging & Disease on 13 March. In an accompanying editorial, Ashok Shetty of Texas A&M University’s Institute for Regenerative Medicine wrote “the overall improvement was quite extraordinary” but stated that larger clinical trials were needed to validate the findings.

Jahar Bhattacharya, a professor of physiology and cellular biophysics and medicine at Columbia University, who was not involved in the work, says injecting mesenchymal stem cells into a patient’s bloodstream remains an unproven treatment for COVID-19 patients and could cause harmful side effects.

“You are injecting large numbers of cells in a patient’s veins,” Bhattacharya says. “If those cells go and clog the lungs, and cause damage because of the clogging—well, that’s not good at all.”

He adds that the study’s sample size is much too small to draw any meaningful conclusions about the treatment’s efficacy at this stage. “Folks do all kinds of things and they’ll say—we got a result,” Bhattacharya says. “It’s very risky to go by any of those.”

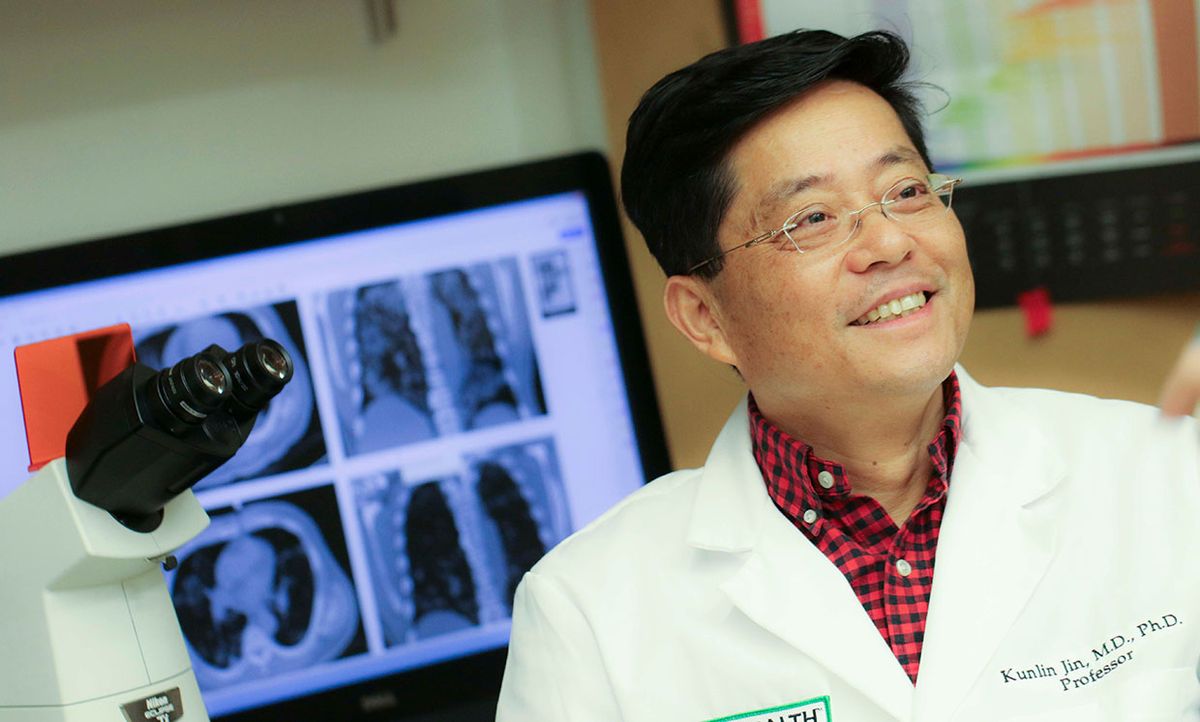

Kunlin Jin, a lead author in the trial and professor of pharmacology and neuroscience at the University of North Texas Health Science Center, says his group now has unpublished data from 31 additional COVID-19 patients who received the treatment. In every case, he claims, their symptoms improved after treatment. “I think the results are very promising,” he says.

According to Jin, 120 COVID-19 patients are now receiving mesenchymal stem cell injections in Beijing for the trial.

COVID-19 is the disease caused by the new coronavirus. There is currently no treatment and researchers around the world are scrambling to identify existing drugs or compounds that could be effective against it.

Jin’s team isn’t alone in considering the use of stem cells to treat COVID-19 patients. Another mesenchymal stem cell trial registered to clinicaltrials.gov aims to enroll 20 COVID-19 patients across four hospitals in China. The Australia-based firm Mesoblast says it’s evaluating its stem cell therapy for use against COVID-19. And in the United States, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority recently contacted the company Athersys to request information about its stem cell treatment called MultiStem for its potential as a COVID-19 therapy.

Mesenchymal stem cells (a term some experts criticize as too broad) can be isolated from different kinds of tissues and, once injected into a patient, grow into a wide variety of cells. They have not been approved for COVID-19 therapeutic use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The new coronavirus invades the body through a spike protein that lives on the surface of virus cells. The S protein, as it’s called, binds to a receptor called angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on a healthy cell’s surface. Once attached, the cells fuse and the virus is able to infect the healthy cell.

ACE2 receptors are present on cells in many places throughout the body, and especially in the lungs. Cells in the lungs are also some of the first to encounter the virus, since the primary form of transmission is thought to be breathing in droplets after an infected person has coughed or sneezed.

However, cells from other parts of the body—including those which produce mesenchymal stem cells—lack ACE2 receptors, which makes them immune to the virus.

In many COVID-19 cases, a patient’s immune system responds to the virus so strongly, it harms healthy cells in the process. Jin explains that, once mesenchymal stem cells are injected into the blood, these cells can travel to the lungs and secrete growth factor and other cytokines—anti-inflammatory substances that modulate the immune system so it doesn’t go into overdrive.

But Lawrence Goldstein, director of UC San Diego’s stem cell program, says it’s not clear from the trial how many of the injected cells actually made it to the lungs, or how long they stayed there. He criticized the classification of patients in the study as “common,” “severe,” or “critically severe,” saying those categories weren’t well defined (Jin says these labels are defined by the National Health Commission of China). And Goldstein noted the lack of information about the properties of the stem cells used in the trial.

“It’s pretty weak,” Goldstein says of the trial design.

Steven Peckman, deputy director of UCLA’s Broad Stem Cell Research Center, adds: “Researchers and clinicians should use a critical eye when reviewing such reports and avoid the ‘therapeutic misconception,’ namely, a willingness to view experimental interventions as both safe and effective without the support of compelling scientific evidence.”

Jin himself doesn’t think most COVID-19 patients should receive stem cell infusions. “I think for the moderate patients, maybe don’t need the stem cell treatment,” he says. “For life-threatening cases, I think it’s essential to use mesenchymal stem cell treatment if no other drug is available.”

Goldstein says other potential treatments for COVID-19—such as drugs that modulate the body’s immune system—appear much more promising than stem cells. Many such drugs have been shown to be safe and effective at regulating the immune system and are already approved by regulatory authorities. It’s also easier to use drugs to treat a large number of patients compared with stem cell infusions.

“When you’ve got a hundred things you want to try, it’s not obvious that this one is on the short list,” Goldstein says of stem cell trials for COVID-19. “It’s a higher priority to test well-known immune modulators than to test these cells.”