It’s the ultimate MacGyver challenge: Fit a sterile, rechargeable electrode through a hollow tube, just 3.8 millimeters wide, to implant the device in a delicate soft tissue without causing damage. The technology must be both simple and inexpensive to build.

Oh, and the survival of a fetus depends on it.

Such was the challenge undertaken by two doctors and an engineer at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, about five years ago. This month, the team published details of the recharging system designed for the completed fetal micropacemaker, and they are now prepared to use it in the first human patient.

About 500 fetuses per year are diagnosed with a rare condition in which the heart beats too slowly to pump sufficient blood to the tiny, developing body. A pacemaker could be used to control that abnormal heart rhythm, yet attempts to place an adult pacemaker in the mother and attach its electrical lead to the unborn child have failed, because the fetus often changes position and pulls out the lead.

“It’s necessary to make the pacemaker small enough so it can be entirely implanted within the fetus with no lead, and you want to be able to do that with minimally invasive techniques,” says Gerald Loeb, a biomedical engineer at USC and co-leader on the project.

The condition begins to impact the health of a fetus about 28 weeks into a pregnancy. Loeb, working alongside cardiologist Yaniv Bar-Cohen of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and Ramen Chmait, director of the Fetal Surgery Program at the USC Keck School of Medicine, developed and tested a device that could be implanted during that timeframe.

The micropacemaker, made of only 7 components, is a slim cylinder designed to fit through the diameter of a 3.8 mm insertion cannula, a hollow implantation tool used in fetal surgeries. The pacemaker itself is “actually very retro in its design,” says Loeb. It relies upon techniques used in the first cardiac pacemakers from the 1950s, such as a simple circuitry—a single transistor relaxation oscillator—and an epoxy capsule. Current adult pacemakers rely on longer-lasting titanium instead of epoxy, yet the fetal pacemaker needs to function for only several months, and titanium was too bulky to fit through the cannula, says Loeb.

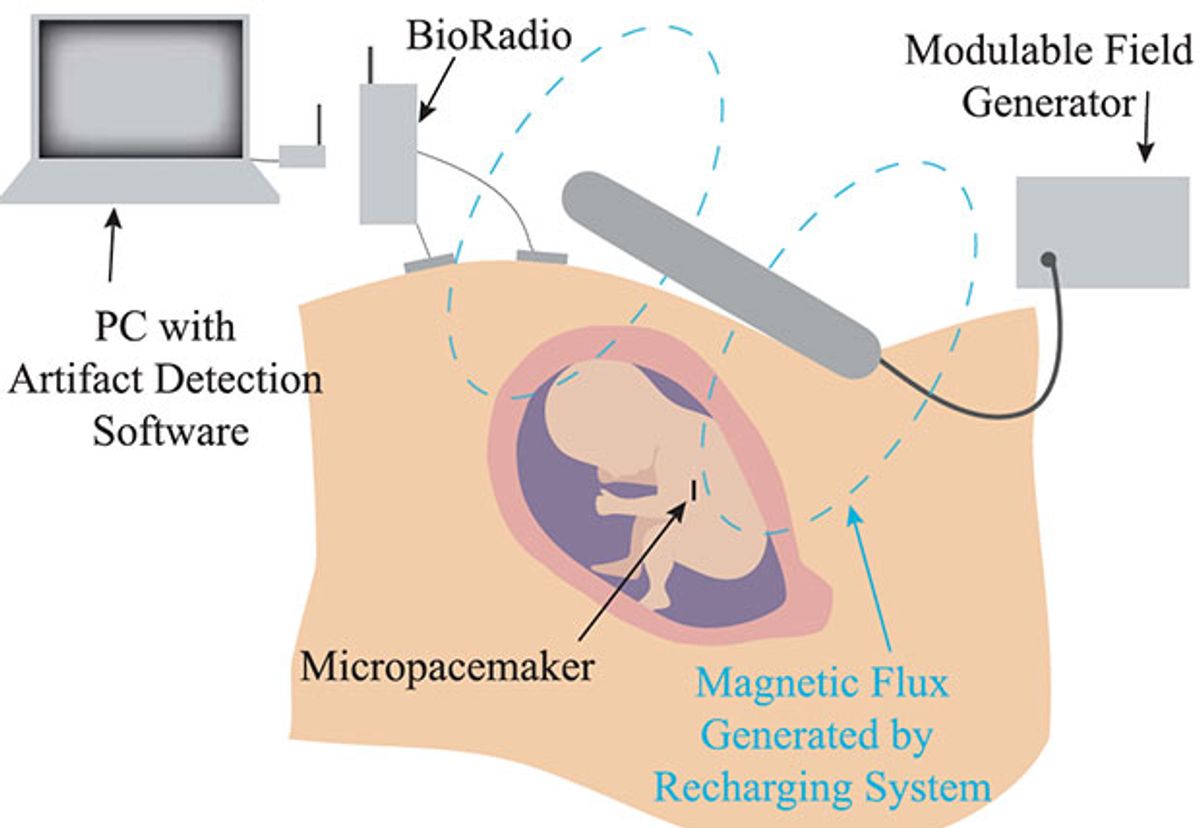

The latest addition to the device was also the most challenging, says Loeb—the wireless recharging system. A small lithium battery within the pacemaker powers the device for only a week, so it must be recharged regularly without being removed. The recharging system relies on inductive coupling: Using a high power field generator, the team creates a radio frequency magnetic field outside the body that couples to the coil inside the implant. By recharging the device every week, the team hopes the fetus can be brought to term with healthy heart function. Then, once delivered, the infant can receive an adult-type pacemaker.

The current device has undergone various rounds of testing in sheep fetuses, a conventional model for studying fetal physiology. In 2015, the FDA granted humanitarian use device status to the fetal micro-pacemaker. The team is now prepared to implant a custom device as soon as a patient emerges. That can be unpredictable due to the rarity of the condition.

“We’ve been testing and refining the recharging system with the actual pacemakers in anticipation of a first patient,” says Loeb. “We want to be prepared, if and when such a patient presents.”

Megan is an award-winning freelance journalist based in Boston, Massachusetts, specializing in the life sciences and biotechnology. She was previously a health columnist for the Boston Globe and has contributed to Newsweek, Scientific American, and Nature, among others. She is the co-author of a college biology textbook, “Biology Now,” published by W.W. Norton. Megan received an M.S. from the Graduate Program in Science Writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a B.A. at Boston College, and worked as an educator at the Museum of Science, Boston.