Because we write so much about futuristic, cutting edge technology, we’re often covering things that are so brand new that only one of them may exist in the world. What we don’t often discuss, though, is how frustrating it must be to get to test one of these 0ne-off inventions out, only to have to give it right back after whatever research you’re participating in has concluded.

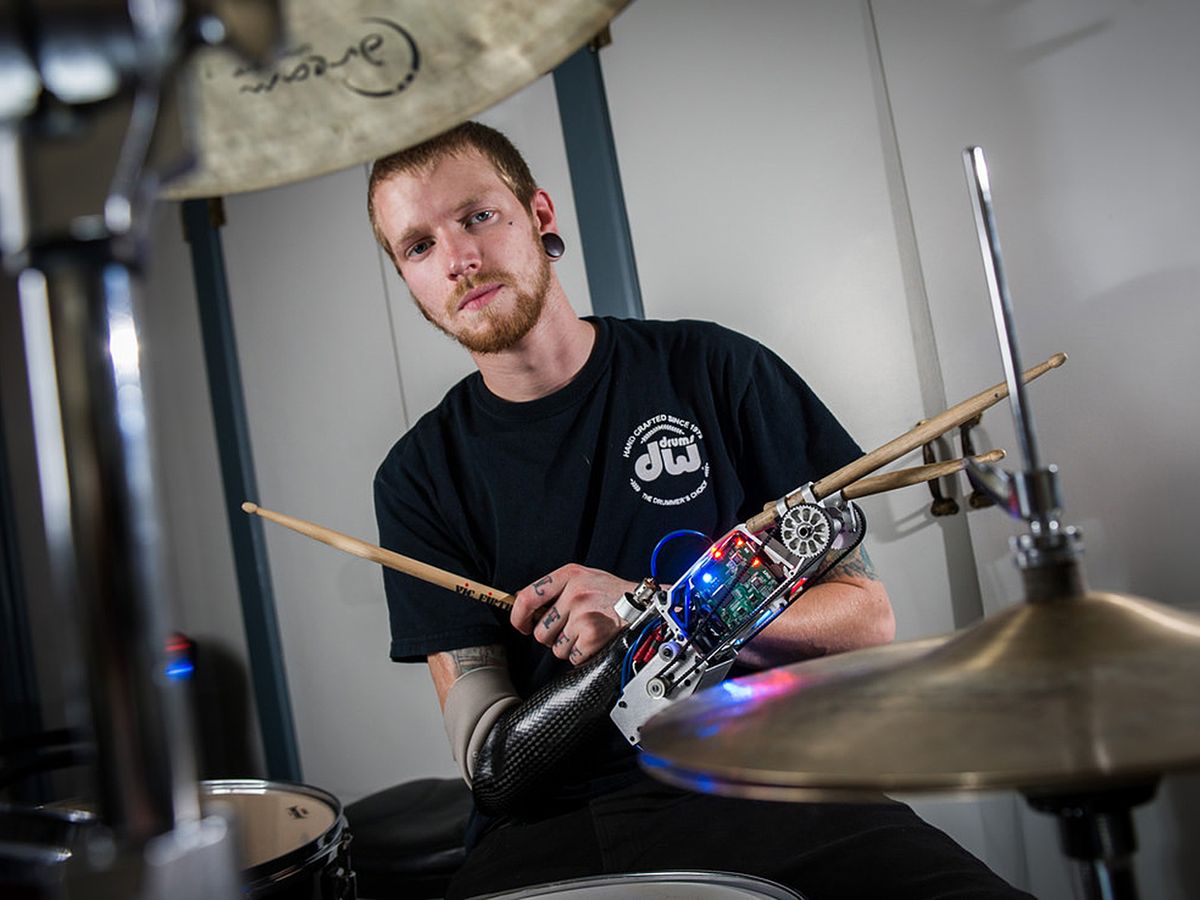

Georgia Tech professor Gil Weinberg has been developing prosthetic limbs that can play music with the help of Jason Barnes, a drummer and amputee. One cyborg arm Barnes has been fitted with allows him to play faster than humanly possible. He's used it in enough performances—including one at the Kennedy Center—that he considers the arm to be a part of his musical identity now. But here’s the rub: The cybernetic arm is technically the property of Georgia Tech, and doesn't belong to Barnes.

Today, Weinberg and Barnes are launching a Kickstarter campaign to raise funds to build a custom prosthetic drumming arm that Jason can take on tour. It won’t be cheap, but Barnes thinks it’ll be worth every penny. With it, he’ll be able to create music that no other human has ever been able to.

The Cyborg Drummer Project Kickstarter is looking to raise $90,000; of that, $70,000 will go straight to production of the new arm. A big chunk of the cost comes from trying to replace the “couple of computers and a technical team” that are currently required to operate the arm with components that are portable, self-contained, and user operated. The remaining $20,000 will go towards organizing concerts and making recordings so that folks who contribute will be able to hear and enjoy some of the result, potentially in person.

One of the unique things about the prosthetic that Weinberg and Barnes want to build is that it will be partially autonomous. There are two drumsticks: Barnes controls one; the other operates autonomously through its own actuator. The arm listens to the music being played (by Jason and the musicians around him) and improvises its own accompanying beat pattern. It's able to do this on the fly, and if it chooses to, is capable of moving at speeds far faster than a human drummer can.

To find out more about the technology behind the arm and what it’s like to play a gig with it, we spoke with Gil Weinberg and Jason Barnes via email.

IEEE Spectrum: Why will it take so much money to make this arm?

Gil Weinberg: We want to allow Jason to explore superhuman abilities (for example two sticks that can play at speeds of 40 hertz— four times faster than the fastest human drummer). The components that allow for such capabilities are expensive. Moreover, building a prototype requires research, experimentation, correcting mistakes, etc., which increases costs. For comparison, other commercial myoelectric prosthetic arms from companies such as Ottobock and Assure cost around $100K. So, our arm is not that expensive. We believe the cost could be reduced significantly if and when we commercialize it for general use, but I don’t see it costing less than $20K-30K even then.

IEEE Spectrum: What kinds of things will your cybernetic arm be able to do that would be impossible for a human arm to do?

Jason Barnes: The arm can play at speeds not humanly possible, it can also play strange polyrhythms that no human can play. It would help boost my creativity and my ability to play.

IEEE Spectrum: The Kickstarter says that “the new arm will allow Jason to control the sticks in novel and innovative ways.” Can you elaborate?

Gil Weinberg: Because the low-latency EMG setup is large and cumbersome, we were only able to allow for the myoelectric control in a lab setting. With the new self-contained and portable arm that we hope to build with the help of the Kickstarter campaign, we will be able to allow Jason to experience and present both low latency dexterous control and the “mind of its own” capabilities on stage.

IEEE Spectrum: As a musician, how do you feel about the partial autonomy that the arm has? Would you want it to have more autonomy?

Jason Barnes: Yes! Jamming with the arm surprises me, and inspires me to be more creative and open to ideas. There are times that it frustrates me, but what musician doesn't get frustrated with other musicians! I think two sticks is plenty, but we would need to work on some of the programming and the AI aspect.

IEEE Spectrum: How do you find the right compromise between autonomy and human control for an inherently creative application like music?

Gil Weinberg: We designed the arm to address both goals, providing the drummer with fine accurate control and subtle expression while also generating new musical ideas based on machine listening and generative algorithms that could surprise and inspire the drummer.

That’s why we designed the arm with two sticks. The first stick responds to Jason’s forearm muscles, basically replacing and augmenting his lost wrist. The second stick has 'a mind of its own': It can play pre-programmed sequences or improvise based on real-time music analysis. Instead of letting the AI balance between these two goals, we let Jason decide when he wants full control, when he wants surprises and inspiration, and when he wants a combination of both. The arm responds to Jason's’ gestures, so when he wants to activate the second ‘mind of its own' stick, he can lift his arm, and start getting inspired. When he wants full control, he can deactivate it and work only with the first stick.

IEEE Spectrum: When you say that support could lead “to innovations that could change the lives of many,” can you give a few potential examples of what might become possible?

Gil Weinberg: We believe that by embedding our myoelectric AI in the a drumming prosthetic arm, we will create technology that would be applicable to other scenarios as well. If the arm can sense the musical and physical environment and respond accordingly, the underling algorithms and miniaturized technology could also improve daily life tasks such as grooming, bathing, eating, grasping, etc.

IEEE Spectrum: What kinds of reactions have you gotten from other musicians that you’ve performed with?

Jason Barnes: I’ve gotten reactions like “wow this is amazing” or “hey this guy is cheating.” Furthermore, people and other musicians are extremely intrigued and interested in how it operates.

IEEE Spectrum: Do you think that this technology has made you a better musician?

Jason Barnes: I think the technology has given me the ability to have my life back but but also the ability to extend far beyond what I had before.

As for the Kickstarter campaign, a $10 pledge will get you a recording of the album that Barnes will produce using his new arm; a $50 pledge will get you a ticket to a live performance in Atlanta next year. Barnes is planning a San Francisco show as well. But personally, I think the most interesting reward is at the $300 level: It’s for musicians who want to see what a robot drumming arm can do. Barnes and Weinberg ask:

Send us your craziest, fastest, most sophisticated percussive MIDI file. We will program the robotic arm to play it and will send you back the audio and video files of Jason playing your beat.

And then you should send those video files to us, because we can’t wait to see humanity get outplayed by a cyborg.

Evan Ackerman is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum. Since 2007, he has written over 6,000 articles on robotics and technology. He has a degree in Martian geology and is excellent at playing bagpipes.