Last Saturday, in a sold-out stadium in Zurich, Switzerland, the world’s first cyborg Olympics showed the world a new science-fiction version of sports. At the Cybathlon, people with disabilities used robotic technology to turn themselves into cyborg athletes. They competed for gold and glory in six different events. [Scroll down for video from two events.]

Rather than celebrating pure human brawn, the Cybathlon rejoiced in the combined power of muscle and machine. The competitors, who were called “pilots,” were people with missing limbs or some form of paralysis; on their own they could never have moved through the races successfully. But by skillfully controlling advanced technologies, amputees navigated race courses using powered prosthetic legs and arms. Paraplegics raced in robotic exoskeletons, bikes, and motorized wheelchairs, and even used their brain waves to race in the virtual world.

[To read more about the Cybathlon's origins, check out IEEE Spectrum's feature article from earlier this year: "Get Ready for the World's First Cyborg Olympics."]

In the exoskeleton race, the pilots all had spinal cord injuries that left them unable to wailk or move their legs. But on Saturday, they strapped themselves into their robotic suits and took off. Exoskeleton technology has come a long way recently. Five years ago, the first commercial exoskeleton from Ekso Bionics was getting its first tryouts in rehab clinics; now Ekso sells its technology for both spinal cord and stroke rehab, and its competitor ReWalk Robotics sells its suit for home use.

Still, the Cybathlon event demonstrated that the technology has a long way to go. The race course required the pilots to stand up from a chair and sit down, navigate a slalom, go up a ramp and through a doorway, walk over stepping stones, and climb up and down stairs. Even with these mundane activities, it was tough going.

In fact, the course was so challenging that some exoskeletons didn’t even make it to the starting line. Organizer Robert Riener, a professor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, notes that 16 exoskeleton teams registered for the event, but 8 dropped out before Saturday. “Exoskeletons are [still] slow and bulky, and cannot perform all kind of steps and tasks,” he tells IEEE Spectrum.

But Riener intended to set a high bar. Like the XPrize Foundation, the Cybathlon’s organizers wanted to harness the motivating power of competition to spur technology development. By filling the races with everyday activities, they hoped to encourage inventors to make devices that can eventually provide winning moves beyond the arena.

And it felt plenty exciting when the pilots went head to head. The top two competitors finished within seconds of each other, with Andre Van Rüschen eking out the victory in his ReWalk Robotics suit.

ReWalk product manager Andreas Reinauer was in Zurich to support his team’s pilot. Reinauer says the company was eager to participate in the Cybathlon to showcase its exoskeleton’s all-around utility. The ReWalk suit is a commercial device that must work for people with a variety of body types, he says, and must help them negotiate all sorts of environments. “Competing and winning against experimental and highly specialized exoskeletons that were designed with only one purpose—to participate at the Cybathlon—shows how well thought out the ReWalk exoskeleton is,” Reinauer tells IEEE Spectrum.

One event moved beyond augmented bodies to focus on pure brain power. In the brain-computer interface (BCI) race, pilots who were paralyzed below the neck used their brain waves to speed their avatars along a virtual racetrack. They wore EEG caps on their heads, which have scalp electrodes that measure the electrical activity of brain cells. While EEG provides only aggregate measurements of brain activity, it can distinguish rough signals as the user shifts between different mental states or tasks. Each BCI has specialized software to parse the data and find the signal in the noise.

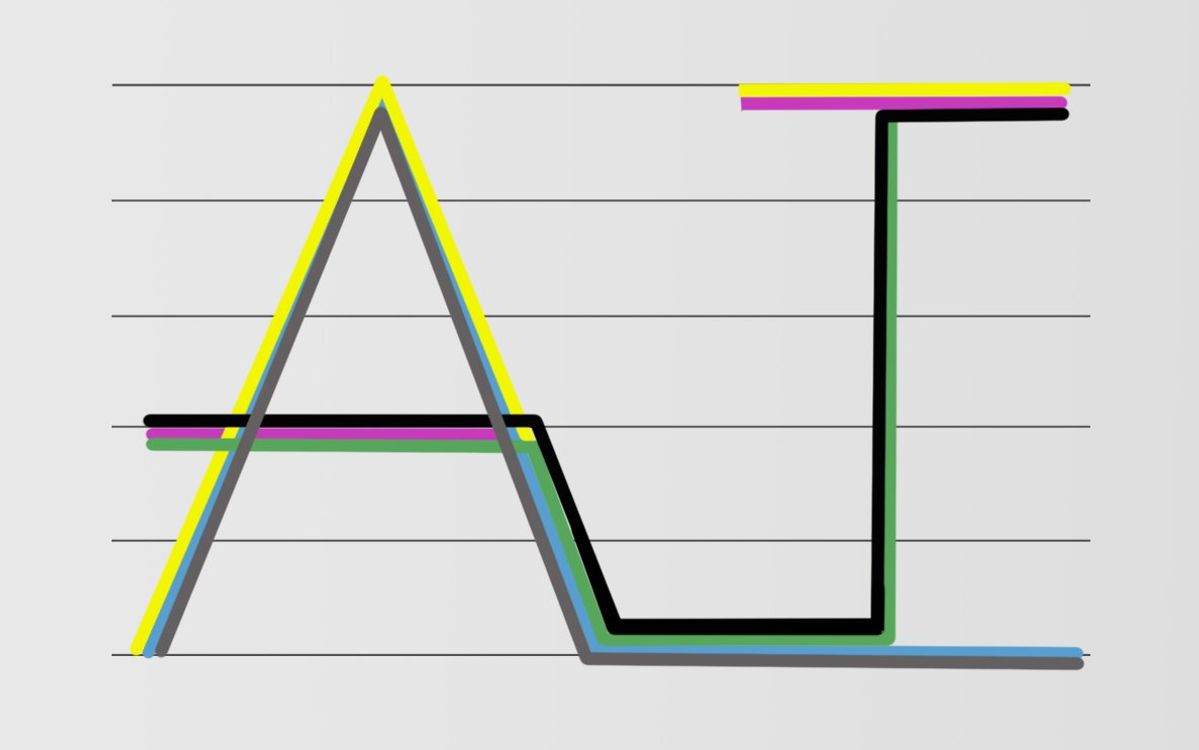

In the “BrainRunners” game, developed specifically for the Cybathlon’s BCI event, the pilots used three different mental commands to hurry their avatars down the track. The different colored track segments required different signals: On the purple segments the pilot had to produce a signal that corresponded to a “jump” command for avatar, and the blue and yellow segments required signals for “rotate” and “slide” commands respectively. The gray segment required the pilot to send no signal at all. Any incorrect commands caused the avatar to slow down.

If you’re hankering for more cyborg athletics, the Cybathlon has posted video highlights on its site.

Tomorrow, we’ll have another post on the bike race, in which paraplegic pilots used leg electrodes to jolt their muscles into action and push on the bike pedals. We’ll have the update from Team Cleveland, the team we profiled earlier this year, which made the USA proud by bringing home the gold.

With 66 teams from around the planet competinng, the Cybathlon felt like a true complement to the traditional Olympics and the Paralympics. Organizer Riener has said the next Cybathlon could occur in 2020 in conjunction with those other tournaments. And with the technologies developing so quickly, those 2020 cyborg athletes may be capable of amazing new feats of skill and strength. Stay tuned.

Eliza Strickland is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum, where she covers AI, biomedical engineering, and other topics. She holds a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University.