Whether you’re streaming a movie on Netflix, playing a video game, or just looking at digital photos, your computer is regularly dipping into its memory for instructions. Without random-access memory, a computer today can’t even boot up.

Over the years, memory has been made up of vacuum tubes, glass tubes filled with mercury and, most recently, semiconductors.

But the first computers didn’t have any reprogrammable memory at all. Until the late 1940s, every time a machine needed to change tasks, it had to be physically reprogrammed and rewired, according to the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester, England.

The first electronic digital computer capable of storing instructions and data in a read/write memory was the Manchester Small Scale Experimental Machine, known as the Manchester “Baby.” It successfully ran a program from memory in June 1948.

Computing pioneers Frederic C. Williams, Tom Kilburn, and Geoff Tootill developed and built the machine and its storage system—the Williams-Kilburn tube—at the University of Manchester.

“The Baby was very limited in what it could do, but it was the first-ever real-life demonstration of electronic stored-program computing, the fast and flexible approach used in nearly all computers today,” said James Sumner, a lecturer on the history of technology at the University of Manchester, in an interview with theManchester Evening News.

The IEEE commemorated Baby as an IEEE Milestone during a ceremony held on 21 June at the university.

How Baby Came to Remember

After World War II, research groups around the world began investigating ways to build computers that could perform multiple tasks from memory. One such researcher was British engineer F.C. Williams, a radar pioneer who worked at the Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE), in Malvern, England.

Williams had an impressive background in radar systems and electronics research. He helped develop the “identification: friend or foe” system, which used radar pulses to distinguish Allied aircraft during the war.

Because of his expertise, in 1945 the TRE tasked Williams with editing and contributing content to a series of books on radar techniques. As part of his research, he traveled to Bell Labs in Murray Hill, N.J., to learn about work being done to remove ground echoes from the radar traces on CRTs. Williams came up with the idea of using two CRTs, and storing the radar trace by passing it back and forth between the two. Williams returned to the TRE and began to investigate the idea, realizing that the approach also could be used to store digital data, with just one CRT. Kilburn, a scientific officer at the TRE, joined Williams in his research.

“The Baby was the first-ever real-life demonstration of electronic stored-program computing, and the fast and flexible approach is used in nearly all computers today.”

A CRT uses an electron gun to send a focused beam of electrons toward a phosphor-laden screen. The phosphors glow where the beam strikes; the glow eventually fades until struck again by the electron beam. To store digital data, Williams and Kilburn used a more powerful electron beam. When it hit the screen, it knocked a few electrons aside, briefly creating a positively charged spot surrounded by a negative halo. Reading the data involved writing to each data spot on that plate and decoding the pattern of current generated in a nearby metal plate—which would depend on whether there was something written at that spot previously.

It turned out that the electron charges leaked away over time (just as phosphors on a TV screen fade) and didn’t allow the tube to keep storing data, according to an entry about the Milestone on the Engineering and Technology History Wiki. To maintain the charge, the electron beam had to repeatedly read the data stored on the phosphor and regenerate the associated charge pattern. Such refreshing is also used in the DRAM present in today’s computers.

In 1946, the men demonstrated a device that could store 1 bit. It is now called the Williams-Kilburn tube; sometimes just the Williams tube.

Also in 1946, Williams joined the University of Manchester as chair of its electrotechnology department. The TRE temporarily assigned Kilburn to work with him there, and the two continued their research at the university’s Computing Machine Laboratory. A year later Williams recruited computer scientist Tootill to join the team. And in 1947 they successfully stored 2,048 bits using a Williams-Kilburn tube.

Building the Prototype

To test the reliability of the Williams-Kilburn tube, in 1948 Tilburn and Tootill, with guidance from Computing Machine Laboratory founder Max Newman and computer scientist Alan Turing, built a small-scale experimental machine. It took them six months, using surplus parts from WWII-era code-breaking machines. And the Manchester Baby was born.

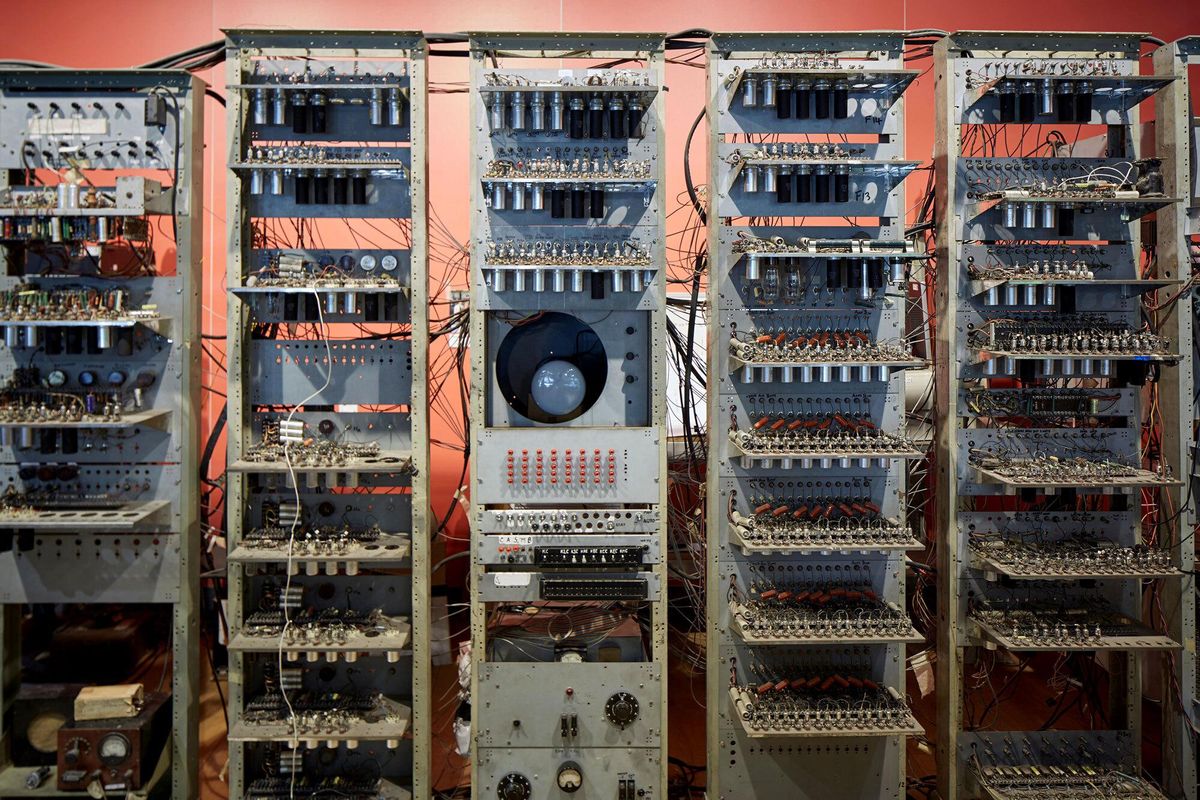

The Baby took up an entire room in the laboratory building. It was 5 meters long, 2 meters tall, and weighed almost a tonne. The computer consisted of metal racks, hundreds of valves and vacuum tubes, and a panel of vertically mounted hand-operated switches. Users entered programs into memory, bit by bit, via the switches, and read the output directly off the face of the Williams-Kilburn tube.

On 21 June 1948, Baby ran its first program. Written by Kilburn to find the highest factor of an integer, it consisted of 17 instructions. The machine ran through 3.5 million calculations in 53 minutes before getting the correct answer.

By 1953, 17 pioneering computer design groups worldwide had adopted the Williams-Kilburn RAM technology.

Administered by the IEEE History Center and supported by donors, the Milestone program recognizes outstanding technical developments around the world. The IEEE U.K. and Ireland Section sponsored the nomination for the Baby. The Baby Milestone plaque, which is to be displayed outside on the Coupland 1 building at the University of Manchester, reads:

“At this site on 21 June 1948 the ‘Baby’ became the first computer to execute a program stored in addressable read-write electronic memory. ‘Baby’ validated Williams-Kilburn tube random-access memories, later widely used, and led to the 1949 Manchester Mark I which pioneered index registers. In February 1951, Ferranti Ltd.’s commercial derivative became the first electronic computer marketed as a standard product delivered to a customer.”

This article appears in the March 2023 print issue.

- How USB Came to Be - IEEE Spectrum ›

- The First Digital Camera Was the Size of a Toaster - IEEE Spectrum ›

- Before Ships Used GPS, There Was the Fresnel Lens - IEEE Spectrum ›

- Take a Trip Through Switzerland’s Museum of Consumer Electronics - IEEE Spectrum ›

- How Microwave Radar Brought Direct Phone Calls to Millions - IEEE Spectrum ›

Joanna Goodrich is the associate editor of The Institute, covering the work and accomplishments of IEEE members and IEEE and technology-related events. She has a master's degree in health communications from Rutgers University, in New Brunswick, N.J.