Africa Calling

Burgeoning wireless networks connect Africans to the world and each other

“Eyes could kill me each time I walked about the streets with my handset,” says Siri Nchise, a 29-year-old customer service representative for an Internet service provider in the African city of Douala, in the Littoral province of Cameroon. In the past five years, she’s had three cellphones stolen. She keeps buying new ones, because they are the only practical way to connect to friends, family, and business associates.

On a continent where rolling blackouts, undrinkable water, and fetid mounds of refuse remain the stuff of everyday existence, wireless telecommunications services stand out as a rare, perhaps unique, technological success story. Tens of millions of ordinary Africans like Nchise carry cellphones today, something not even the richest of them could have possessed barely a decade ago. And every month, millions more dial in to the 21st century, with profound implications for African economies and societies.

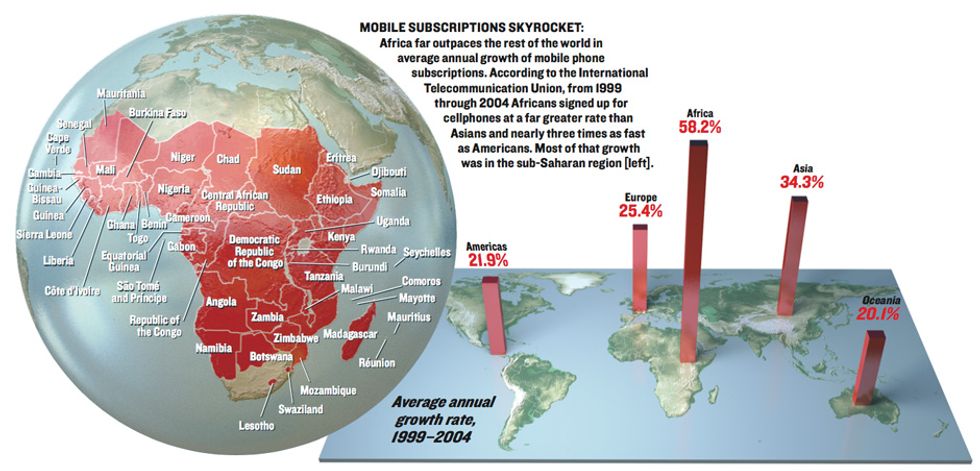

It might come as a surprise that sub-Saharan Africa—with 34 of the 50 poorest countries on Earth, according to the United Nations—is now the world’s fastest-growing wireless market. But there’s no arguing with the statistics: the number of mobile subscribers in 30 sub-Saharan African countries, not including South Africa, rose from zero in 1994 to more than 82 million in late 2004, according to the latest figures from the International Telecommunication Union, in Geneva. The rate of growth for the entire continent has been more than 58 percent per year, compared with the almost 22 percent annual growth rate in the Americas; in Cameroon, Kenya, Senegal, and Tanzania, growth rates are running in excess of 300 percent. Nigeria, Africa’s largest country, with 140 million inhabitants, has only about 500 000 landlines, or approximately 1 for every 280 people. In that country 19 million mobile phone subscribers have signed on since 2000, and the Nigerian Communications Commission projects the total number of subscribers to grow to 50 million by 2010.

Africa is going wireless for a very simple reason: its national telecommunications monopolies are poorly managed and corrupt, and they can’t afford to lay new lines or maintain old ones. So in most sub-Saharan countries not even 1 percent of the population have landline-connected telephones. That compares with more than 10 lines per 100 people in Latin America and more than 64 per 100 in the United States. Indeed, Tokyo and New York City each have more fixed-line telephones than the whole of sub-Saharan Africa. These numbers are even more daunting when you consider that fixed lines tend to be concentrated in capital cities, leaving rural communities totally bereft. For instance, while the country of Senegal has about 140 000 lines, 65 percent, or 91 000, of those lines are in the capital city, Dakar.

More than just inadequate landline networks and institutions are fueling Africa’s wireless boom. Growing political stability has helped to attract foreign investors to a region decimated by civil wars over the past 50 years. And the far simpler logistics of getting a wireless network up and running are also an enormous factor in sub-Saharan Africa, where even the seemingly straightforward can turn out to be anything but.

During our recent travels in Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, and our home country of Cameroon, we’ve seen why wireless networks have succeeded so spectacularly where landlines failed so miserably. Landlines can take years to install even after the right palms have been greased, while you have only to buy a handset and prepaid cellphone calling card to get a wireless line. In addition, companies can erect base stations that cover a radius of 35 kilometers for much less than it would cost to run copper cables from central exchanges to every customer’s phone.

But that’s only part of the story. The African cellphone revolution thrives on a combination of a novel business model introduced a decade ago in South Africa and some clever calling tactics that have made cellphone usage affordable for a large segment of the population. As a result, growing numbers of Africans at the top, middle, and even bottom rungs of the economic ladder depend on the wireless sector for their livelihoods. But can the region sustain the wireless sector’s phenomenal growth rates and accompanying prosperity? And does the capital flowing in and out of these countries via transnational wireless corporations represent a sustainable infusion of desperately needed foreign investment, or neocolonialism dressed up as a free-market bonanza?

The sparks that ignited the African cellphone explosion occurred in South Africa in 1993, when the government granted national cellphone licenses to MTN South Africa Ltd., Johannesburg, and Vodacom Group (Pty.) Ltd., Sandton. These companies, each partially owned by the South African government, quickly built large customer bases in South Africa, and eventually other African nations, by offering prepaid cellphone cards. These cards draw customers who can’t afford monthly phone bills, don’t have postal addresses, or don’t maintain checking accounts. People pay as they go, and only as much as they can afford.

These cards brought telecommunications to the masses. The East African country of Uganda is a prime example. Most Ugandans do not meet the financial criteria for subscription-based service. Nevertheless, in the three years following Kampala-based MTN Uganda’s introduction of a prepaid option, Uganda’s overall mobile telephone density quadrupled, rising from 0.41 subscribers per 100 people to 1.72. Today, more than 50 percent of the population has mobile cellular coverage. More than 98 percent of Uganda’s mobile subscribers use prepaid cards. By the end of 2001, over half of Africa’s countries—28 nations—had more mobile than landline subscribers, a higher percentage than on any other continent [see figure, "Mobile Subscriptions Skyrocket"].

As instrumental as these cellphone cards have been, they weren’t the only factor that set the stage for Africa’s wireless boom. Africa’s national telecommunications monopolies created business opportunities for multinational carriers by not servicing their citizens with landlines. Telkom Kenya Ltd., in Nairobi, for example, which has only 313 000 landline subscribers in a country of 30 million people, won’t invest in new lines. Instead, Telkom has met demand for phone service by partnering with foreign companies that are putting in new wireless infrastructure. In 1999, it formed Safaricom Ltd., Nairobi, which it owns in partnership with Newbury, England-based Vodafone Group PLC (which also owns part of South Africa’s Vodacom). The next year, the Communications Commission of Kenya licensed KenCell Communications Ltd., now Celtel Kenya, Nairobi, to provide service based on the GSM 900 standard used throughout Africa.

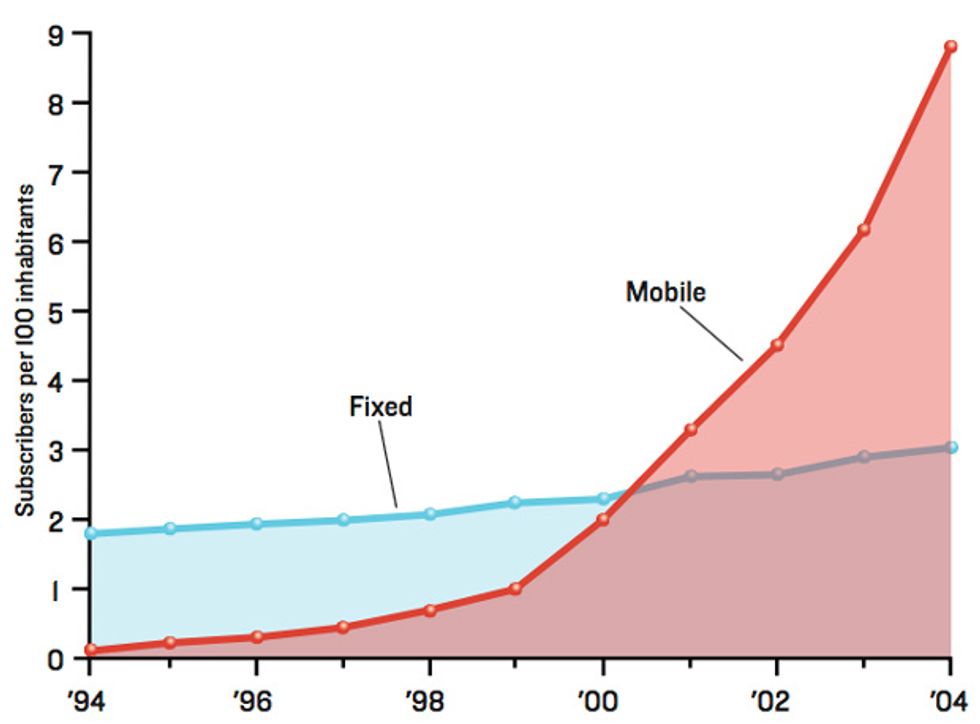

These companies have succeeded far beyond their expectations. According to London-based TeleGeography Research, on launching its service in 1999, Safaricom expected to have 3 million subscribers by 2020. By the end of 2005, there were more than 4.6 million wireless subscribers in Kenya, split between the two carriers. Safaricom projects that it alone will have 5.5 million subscribers by the end of 2007 [see graph, "Mobile vs. Fixed Lines in Africa"].

Countries that liberalize their telecommunications markets often create feeding frenzies among multinational and local wireless companies alike. For example, though MTN was first to provide cellphone services in Nigeria, the company now finds itself in heated competition with South Africa\0x2013based Econet Wireless International and Nigeria-based Globacom, as well as about 10 smaller carriers. Wireless enterprises have been so successful that the Nigerian government is now trying to privatize its own hapless monopoly, Nigerian Telecommunications Ltd., based in the capital, Abuja, and its wireless division, Mtel. But with such a competitive wireless market, the Nigerian government has had a hard time finding a suitor for Nitel Ltd. TeleGeography reports that the monopoly, which currently has 10 000 employees, had not paid workers for more than two months as of March, and that it plans to slash 6000 jobs by the end of May.

Africa has seen economic booms before —from oil, diamonds, and more—but hardly any have benefited ordinary Africans. This one might be different.

As of March 2004, the telecommunications sector was the fastest-growing employer in Nigeria. It directly employed 5000 people, indirectly employed 400 000, attracted more than US $4 billion in investment the year before and contributed about 3 percent to the gross domestic product—and this was when Nigeria’s cellphone companies boasted only 4 million subscribers. There are more than 19 million today.

While carriers can provide jobs to qualified engineers and administrators, indirect employment can help spread the wealth even to those who don’t have the benefit of education or the right connections. Again, without reliable data to consult, we must rely on our own observations to document the trickle-down effect wireless carriers are having on African economies. One indicator of the telecommunications industry’s deep penetration into the everyday economy is the ubiquitous wireless-phone kiosk, where customers can rent mobile phones by the minute.

Cheap to set up and lucrative to operate, kiosks often provide a family’s sole income stream. Owners initially invest about $100 to build a small shack and to buy a handset and charger, an expense of $40 to $60. The SIM card and activation could cost another $10 to $20. In Kenya, mobile-service entrepreneurs often forgo the shack and instead carry handsets on lanyards around their necks, finding customers as they stroll around marketplaces.

The average cost of a 3-minute mobile-to-mobile phone call in sub-Saharan Africa is 57 cents. Overseas calls made from a wireless phone are an even greater bargain, which has let African businesses connect to foreign partners at much cheaper international calling rates than those charged on landlines. For example, the average cost of a call from Cameroon to the United States is 50 cents per minute using a mobile phone, while the same call on a landline phone is $6 per minute. That’s because most landline international phone calls from Cameroon are routed through France, which charges switching fees. Wireless telephony helps Africans bypass the European tollgate and bounce calls to satellites for long-distance service.

Most kiosk owners we surveyed in Kenya charge about 25 cents per minute for a local call and about 50 cents for an international one. Kiosk owners and strolling vendors alike earn as much as $400 per month, much more than what many college graduates earn at Kenyan corporations.

The sale of prepaid cards themselves has become big business. In Cameroon, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda, most convenience stores do brisk business selling prepaid phone cards. Informal evidence suggests that these cards generate thousands of dollars per year in extra revenue. Card sellers who do not own convenience stores stand by the roadside or trawl through traffic jams to ply their trade [see photo, "Curbside Service"]. Card vendors make more money than government secretaries and elementary school teachers do; many of them own one or more mobile phones themselves.

In fact, ambitious kiosk owners—and many business people—often need to own multiple handsets to place calls on a country’s separate networks. That’s a direct result of the failure of telecom regulators to mandate that networks interoperate. In most sub-Saharan countries, wireless companies do not allow rivals access to their networks. (This is also true of countries in other turbulent and developing regions; see “Iraq Goes Wireless,” in the March 2006 issue of IEEE Spectrum.) MTN and Vodacom customers can’t place calls to one another. In the short term, totally separate networks translate into more handsets for people who can afford them and more customers for certain carriers. In the long term, the industry risks increasing customer dissatisfaction as the novelty of ready access to telecommunications wears off and customers begin to demand better quality of service.

For both good and bad , the age of affordable cellphonesis as much a social phenomenon as an economic revolution. Equipped with mobile phones, poll-watching citizens can instantly report ballot fraud. Spouses cheat on each other by secretly and silently arranging dates via text messages. And criminals go to extreme lengths to get their hands on coveted handsets, sometimes even impersonating taxi drivers and picking up only passengers carrying handsets they want to steal.

The sub-Saharan region is notorious for its history of undemocratic practices. Its checkered past is littered with stories of nominally democratic elections that have been hijacked by incumbent presidents. But this situation is changing with increased access to wireless technologies, news media, and the Internet, which have combined to educate Africans about democratic practices and human rights.

A good example is Senegal’s 2000 presidential election, when citizens armed with radios and cellphones helped to prevent incumbent president Abdou Diouf from rigging the elections. During the balloting, city-dwelling Senegalese walked around with handheld radios and mobile phones. Radio stations sent reporters to hundreds of individual voting bureaus. Within minutes of the local officials’ announcing the result, the reporters got on their mobile phones and broadcast it. Given the situation, it was difficult for the authorities to massage the result without the electorate’s knowing all about it. Diouf, who had been president since 1981 and had come in a clear second to president-elect Abdoulaye Wade, peaceably abdicated power.

Election monitoring isn’t just good for democracy; it can be good for business, too. In Kenya, Safaricom gives paying customers election results via text messages. It launched its Get-It 411 short message services in 2002 to provide subscribers with local and international news, sports scores, horoscopes, movie listings, inspirational quotes, and election updates, each of which can be sent to the user for a fee of 7 shillings (about 10 U.S. cents) per message.

While some Africans wield their cellphones to protect their fledgling democracies, others thumb the keypad for that most prurient of purposes—the booty call\0xFEFF. Mobile telephony provides a new, convenient way to carry on affairs without risking a spouse’s overhearing plans for an illicit rendezvous. Lovers often communicate with text messages or “beeping”—one party dials another’s number and then hangs up. Beep buddies usually work out a code between themselves. One ring could mean, “I am here,” two rings, “Call me now.” In most of Asia, Europe, and Africa, where the calling party pays only upon connection, beeping is a cheap way to send a signal.

That’s not to say that the carriers are losing out when facilitating love connections. On the contrary, an affluent, philandering husband may be great for business. His social network depends on him: the more ladies he romances, the bigger his network grows, and the more people he pays to connect. Say John has three phones, one for his wife and family on one carrier, one for his business on another, and one for his mistress on yet another. He will almost certainly buy seven phone cards: three for himself, one for his wife, one for his parents, one for his wife’s parents, and one for his mistress. His mistress might ask him to buy a phone card for her mother and her sister. One paying user, but nine times the business.

While it is impossible to precisely quantify the impact such social networks might have on the phenomenal growth wireless carriers currently enjoy, the consequence of one man’s losing his livelihood could be that nine fewer phone cards are purchased during a particular time. Scale up those numbers in the event of an economic downturn, and a country’s cellphone boom could quickly go bust. Looking only at the number of subscribers that carriers trumpet in their press releases doesn’t tell the whole story. As we’ve seen in our travels, there’s a serious need for more comprehensive, quantitative studies of both the economics and the social dynamics that underpin Africa’s wireless sector.

Africa no longer has a problem with the lack of telecommunications infrastructure, because most of the region’s inhabitants are now, or soon will be, covered by mobile signals. In the long run, however, some countries might have trouble sustaining these new services, partly because of a lack of investment strategies and financial management skills at the street level and partly because of capital drain, a hidden consequence of the privatization policies that have fostered Africa’s wireless boom.

We view this boom and the jobs it brings with cautious optimism. On the one hand, cellphones have triggered a substantial increase in complementary service jobs, such as vendors who sell prepaid cards, cellphone covers, handsets, and headsets. It is still the case, however, that most vendors live hand-to-mouth, not surprising in these traditionally agrarian societies. Neither kiosk owners nor street vendors are saving for future business investments that might eventually help them move beyond subsistence. We recommend that African governments provide basic financial management training programs for vendors, especially kiosk owners, who need help to look beyond their immediate financial gains to a sustainable future.

The issue of sustainability extends to businesses as well. More than 80 percent of cellphones purchased in sub-Saharan African countries are for personal use, not business. In fact, fewer than 10 percent of the region’s businesses provide employees with cellphones for day-to-day business-related transactions. If this trend continues without aggressive endeavors to leverage wireless telecommunications to promote other economic sectors, the new economic ladder erected by the wireless industry will rest on very shaky ground indeed.

Finally, there is the issue of capital flow. The privatization process in most sub-Saharan countries aims to attract both local and foreign investors. It is often the case, however, that privatization hinges almost entirely on foreign investments, especially from Europe and the United States. Foreign investors bring resources that most local investors do not, such as the initial capital for infrastructure, and they tend to win the majority of wireless licenses. Although this could be a good strategy in the short run, it remains to be seen whether this approach promotes sustainable development within the region, considering that most of the returns on such investments accrue to foreign shareholders and are not plowed back into Africa—a typical form of neocolonialism. African regulators need to develop strategies to promote local investments in the wireless arena, as well as in other telecommunications sectors. They could benefit tremendously from more research in this area.

That said, foreign investment is key to raising the incomes and living standards of Africans. There is still a long list of items that African nations and the world at large need to address—including electric power, housing, clean drinking water, public health, and education. But at least now we can check off telecommunications. Wireless carriers have connected individuals and businesses to the rest of the world and, most important, to each other. It’s a giant step on the long road to development.

About the Authors

Victor W.A. Mbarika, Ph.D., a native of Cameroon, is a technology consultant and a professor of e-business at Southern University and A&M College, in Baton Rouge, La. Irene Mbarika, a former customer relations manager for Douala 1, an ISP in Cameroon, now focuses on medical technologies for Africa.

To Probe Further

For more about the growth of wireless telephony in Africa, see M-Commerce in Africa—Innovation Overcoming Barriers, by P. Hamilton, World Markets Research Centre, 2002, https://www.wmrc.com.