Real-Time Search Stumbles Out of the Gate

Experts say instantaneous info is cool, but real-time search isn't quite ready for prime time

Real-time search is trending. Late last year, Google and Microsoft rolled out much-anticipated real-time search engines, with Yahoo hard on their heels. A plethora of smaller start-ups offer services from Twitter searches to more comprehensive info grabs. But early results are in, and so far these engines aren’t skating straight 6s.

”So far, I’ve been pretty underwhelmed by the real-time search efforts,” says blogger and tech expert Robert Scoble. Search Engine Land editor Danny Sullivan also cautions in a blog post that while the idea of real-time search is exciting, ”search engines are acting a bit like cats getting a sniff of catnip. They’re high on real-time search and acting kind of crazy.”

In a nutshell, real-time search means finding, indexing, and displaying in a search window any results that have just been posted to the information ether—be it a 140-character tweet, a status update on Facebook, a new blog entry, a photo, or even a news article. Search engines big and small are falling over themselves to roll out the technology that makes it happen.

Real-time content is ”cool,” Sullivan says, because there is ”some content that only exists in these microblog formats,” his label for tiny, instantaneous snippets of information. Driving home one night in December, for example, Sullivan found a tree that had fallen and was covering all the lanes in the road. ”It just happened—no news outlet had covered it yet, so I put out a picture and the location [on Twitter],” he says. ”More and more you see this real-time content out there. And people want to get at it.…If you don’t index these kind of stories, you miss them.”

But as more information gets added to the Web, search engines have to find better ways to sift through that content. According to Filippo Menczer, an Indiana University professor of informatics and computer science, the question is: How can we make sure that search engines can access information that was posted 2 minutes ago, even though their crawlers might visit a site only once a day or once a week? If someone tweets about an earthquake but you don’t see the post until a week later, Menczer says, ”that’s not useful.”

Enter real-time search.

Sullivan argues that the term ”real-time” should include only information that’s written and posted immediately. Basically, that means a tweet or a Facebook status update. Even a blog takes time to write, he says, so by the time it’s posted—even if it’s immediately available through instantaneous search algorithms—the ideas in it are old news, and therefore not real-time.

But to Stefan Weitz, director of Microsoft’s Bing search engine, real-time search is ”a lot more than tweets or status updates.” There are dozens of ways to put out real-time information, Weitz points out. There’s photo tagging, YouTube, and MySpace, and ”most of these forums have a temporal aspect,” he says. But sometimes information from two hours ago—or even last week—is real-time enough, he argues. It just comes down to the user.

For example, Bing’s recently released Bing Maps includes an application called Local Lens, which scans local community blogs and links to them, allowing a user to scroll over locations on a map to find out what’s happening around town. Those blogs are updated a few times a day, Weitz says, which wouldn’t be real-time according to Sullivan. Still, ”that’s real-time-ish,” Weitz maintains. Sure, it’s ”not as real-time as Twitter,” but it could still make a difference in deciding what to do on a Saturday night.

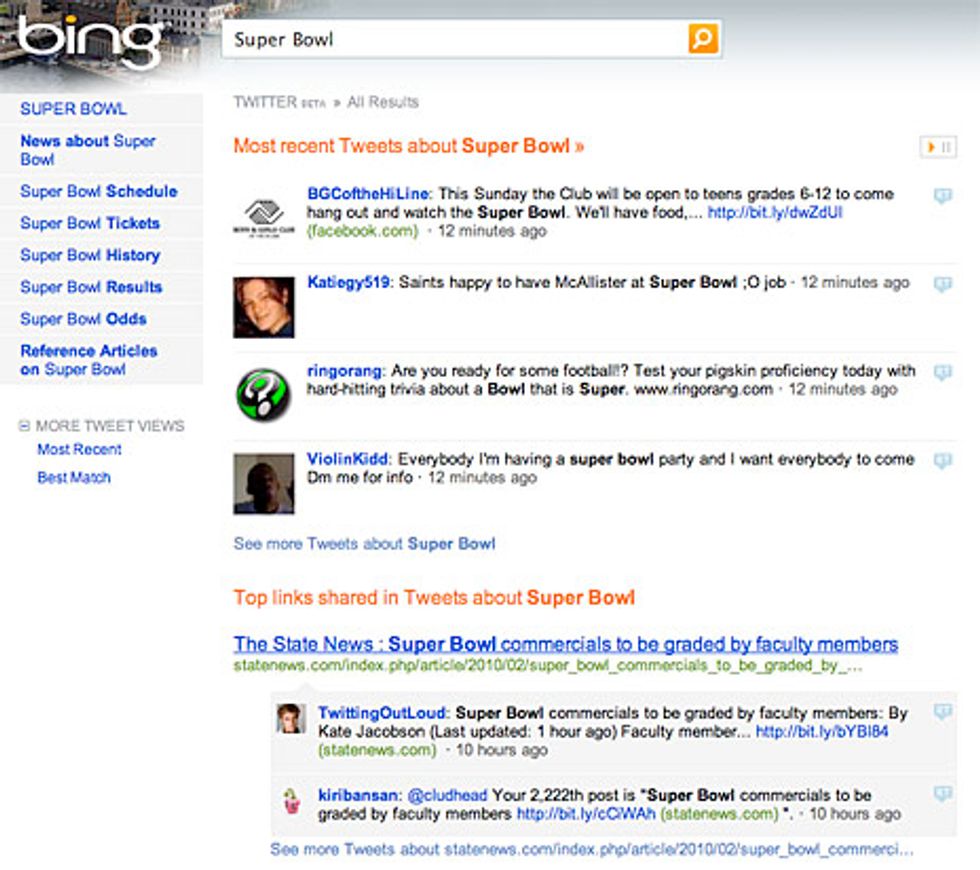

Key to this instantaneous search technology is having access to the data streams. ”[Search engines] can’t crawl so fast, so they need agreements” with the key information sources, says Menczer, who is also associate director of IU’s Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research. Accordingly, Bing and Google got access to Twitter’s ”firehose feed”—all the data streaming in from every tweet—last October. Bing got Facebook data at the same time, and Google got Facebook plus MySpace in December.

Once the search engines have all this data, of course, the trick is figuring out what to do with it. Even ”assuming we have access to much of this content,” says Menczer, ”it’s no longer in the tradition of Web text and hyperlinks.” So PageRank, Google’s tool for ranking Web sites—and, ultimately, the relevancy of results to a particular search—”may not be readily applied to social Web,” he says.

Google’s search guru Amit Singhal acknowledges that to corral all this content into a results page isn’t easy, and PageRank depends on building authority over time. So while Singhal indicated at last December’s product release press conference that PageRank is still an important part of the engine’s ranking ability, other signals have to be added to make real-time search a powerful tool. Google engineers had to develop ”at least a dozen new technologies” to pick out the most relevant pieces of information from the mass of data flooding the Web, including models of volume fluctuation (for instance, when a lot of tweets suddenly come in on a specific topic) and new language models (is it genuine information, or is it a ”weather buoy” tweeting automatically?).

To capture the right info, Google first filters out spammy tweets and then ranks the remaining tweets according to the time they came in, says Sullivan. If people are new to Twitter and have never tweeted, they won’t rank very high in the search results. And if they have no followers, Google will try to detect that as well.

Bing’s Weitz explains that beyond its core Web safety algorithms, which sift out spam and adult content, Bing adds special algorithms to track the usefulness of Twitter data. Because many tweets have the same basic idea (for example, say everyone is tweeting about Tiger Woods), Bing algorithms try to ”unduplicate” the tweets to come up with one main idea. The algorithms try to evaluate the authority of a tweet and eliminate false information based on whether the tweet is coming from just one person and whether it’s been ”retweeted.” They also attempt to determine authority by looking at how many people are following someone on Twitter, how many times that person is retweeted, and whether he or she tweets often.

At least that’s the goal. But Web watchers aren’t convinced it’s working.

In addition to creating a potential spam nightmare, real-time search hasn’t adequately tackled the issue of relevancy, experts say. In a December Search Engine Land post, for example, Sullivan dissects Google’s real-time results related to the death of actress Brittany Murphy that month, which he argues was the first true test of Google’s real-time search engine. It didn’t exactly ace the exam.

Though Sullivan admits he wasn’t there to observe whether the information came out in seconds rather than minutes—compared to the news of Michael Jackson’s death, which ”took several minutes to make it into Google despite the extraordinary number of searches it was getting”—his main complaint was that neither Google nor Bing produced the most relevant results half an hour after the news hit the e-waves.

Robert Scoble agrees. ”There’s no ranking by authority that I can tell,” he says. For example, throughout the 27 January release of the Apple iPad, Scoble tried to find some original, insightful, real-time content on Google and Bing. What he found instead was a tweet on Google about how cool the tablet would be. Scoble was not impressed: ”Four hundred tech bloggers are pouring info into Twitter, and this is the most important tweet they picked?” He had to go back to Twitter’s own search function to find the most recent iPad conversations.

Google also makes it hard to figure out where the real-time results are, Scoble complains. They appear only on some pages, he says, and when they do pop up, they’re often in different places on the page, depending on the topic, which he finds disconcerting and confusing. ”They need to put it in the same place so you know where to find it,” Scoble says.

Plus, he adds, there’s ”no visual cue” telling a reader that one article is better than another. As a counterexample, Scoble offers Techmeme, which displays its most important articles in a larger font in the upper left-hand corner of the page. No such easy hints on Google.

Scoble further laments that Google doesn’t explain how the results are organized or chosen. ”With PageRank, you can sort of figure it out,” Scoble says, because sites are ranked according to how many other sites are linked to their home page. But with Google’s real-time results, he says, ”you have no idea why they’re on the page or how they’re ranked.”

IU’s Menczer suggests that with all this user-generated content, the environment is more complex than the one Google’s PageRank algorithm had to deal with. While search used to be about relationships between pages, he explains, now it’s about relationships between ”people, tags, Web pages, ratings, votes, and direct social links….It may not be that page A points to page B but rather that user John follows Mary and replies to the tweet of Jane and retweets it.” That makes it ”a more complicated ecosystem,” he says, ”but a very rich one,” and search engines will need ”more sophisticated ways to extract data from these relationships”—more sophisticated, perhaps, than they are already trying to be. Bing fared even worse than Google in Scoble’s litmus test, with its number one search result for ”Apple iPad” on the release day returning a blog post from 2007 that ”has nothing to do with this new product,” Scoble says.

So neither Google nor Bing is doing anything interesting with real-time data, according to Scoble—at least not yet. ”There’s no explanation, no transparency, no depth, and no value,” he says.

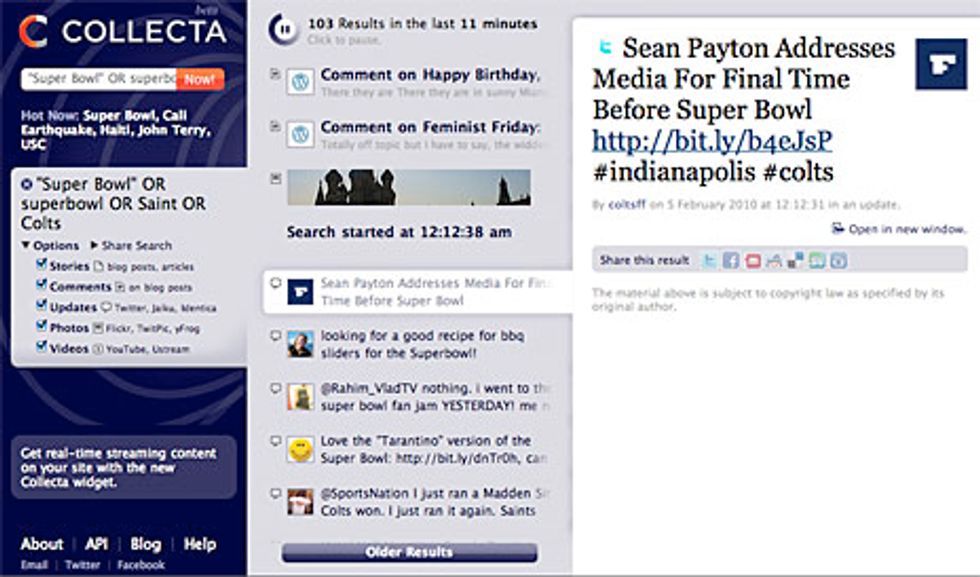

An explosion of start-ups, however, is betting on the real-time bandwagon. Countless smaller search engines do anything from Twitter-only searches to ”meta” searches of the whole Web to bring you the latest information from friends and strangers.

Collecta, for example, searches Twitter, MySpace, news, and blog sites, including comments on Web posts, with streaming real-time results. Two weeks ago, Collecta launched an additional widget feature that lets users drop its real-time search stream onto any Web site or blog—spreading real-time search results, and its own visibility, throughout the Web.

Other start-ups like OneRiot (formerly Me.dium), Tweetmeme, and Topsy search only the links that are shared on Twitter, rather than what tweets are saying [see this update for the latest on Topsy's just-added search features]. With a lot of ”stupid stuff” out there, according to Scoble—such as a tweet about the Haiti earthquake that says ”OMG that’s so awful”—that filter function could be helpful.

But Scoble hasn’t seen any of the smaller real-time search players do ”anything beyond what Twitter Search does in any good way.” Bing’s Weitz grants that the smaller real-time search engines may prove useful, mostly because they ”don’t have to support 100 million users,” which means they can do ”computationally harder things.”

Menczer says they won’t have much of a role, however. ”When you have the industry coalescing around a few big players, small start-ups with clever ideas either get acquired—to get their technology or their people—or they will just sort of lose out generally.” In the case of search, he says, it is ”especially hard to fight the establishment.” Sullivan agrees that now that Bing and Google have gone whole hog, it will be less compelling for users to go to smaller sites.

Still, those major search engines have a lot of kinks to work out. Because real-time search is a relatively new feature, Scoble says, search engines ”haven’t figured out a usage model, or what it’s good at, or for.” So far, he suggests, real-time search is not yet good at showing how the world is reacting to the Apple iPad. Or the Haiti earthquake. Or Brittany Murphy.

Sullivan adds that it’s hard to know what people want from search features. ”These [tweeters and status updaters] are hyper-real-time authors, not ordinary people. They’re the ones using this stuff,” he says, ”but what about non-real-time authors?” He wants to know how regular people will use real-time search, not just the people who are immersed in it daily.

Scoble, for one, wants to see the ability to search tweets months after the fact, which isn’t possible when they disappear from the Twitter Search index after two weeks. It would also be nice to search certain lists, such as a list for venture capitalists, he says, instead of having to scour the whole of Twitter. List searching would narrow a search from a billion tweets to, say, 100 000 or 10 000, so ”you’re much more likely to find that needle in a haystack,” Scoble says.

So what would a proper real-time search engine look like?

”Well, people haven’t seen it,” Scoble says. ”In the horse-and-buggy days, if you asked someone what they’d want in a new buggy, they’d say, ’Better wheels, better shocks, maybe a nicer-looking horse.’ But they wouldn’t be able to say, ’I’d like a car with an engine, and fuel that isn’t food.’ Once people see a search engine that works, they’ll say, ’Oh, that’s so cool.’ But until they see it, they can’t describe it to you.”

To Probe Further

Read in-depth comparisons of start-up real-time search engines at Search Engine Land and at VentureBeat.

Read a comparison of Google and Bing real-time search engines.