Protecting Online Privacy

We do care about our privacy online, and we can protect it from surveillance

This is part of IEEE Spectrum’s special report on the battle for the future of the social Web.

Privacy is no longer a “social norm,” Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg said last year. At first glance, it seems that Zuckerberg is right. More than half a billion people use his site to share all sorts of intimate details of their lives with others loosely defined as “friends.”

In your own life, you've likely noticed that people are broadcasting details that they used to reserve for small circles of friends. They announce when they break up with a romantic partner as casually as they mention what they are cooking for dinner or where they are shopping. Teens and twentysomethings seem particularly fond of such sharing, leading many people to conclude that younger people care little about privacy.

But Zuckerberg is wrong, and the fact that you know what your cousin had for dinner doesn't change that. Privacy does matter to everyone, regardless of birth date. Even if you opt to tell many people when you are drunk or with whom you are

sleeping, you care about privacy. It’s not about what you share and where you reveal it. Privacy is about the fact that you have a choice in what you reveal and that you exercise the choice knowingly.

Zuckerberg is using a different and overly simplistic definition of privacy. By this definition, privacy covers only a set of aspects or actions that people generally wish to keep to themselves: essentially, matters of sex, drugs, and—occasionally—rock and roll. Using such a definition is convenient for Zuckerberg because ignoring the real meaning of privacy helps him run his business without fear or guilt.

When we complain about infringements on our privacy, what we really are demanding is some measure of control over our reputations in the world. Who should have the power to collect, cross-reference, publicize, or share information about us, regardless of what information that might be? If I choose to declare my romantic status to my friends on Facebook, then at least it's my choice, not Facebook's.

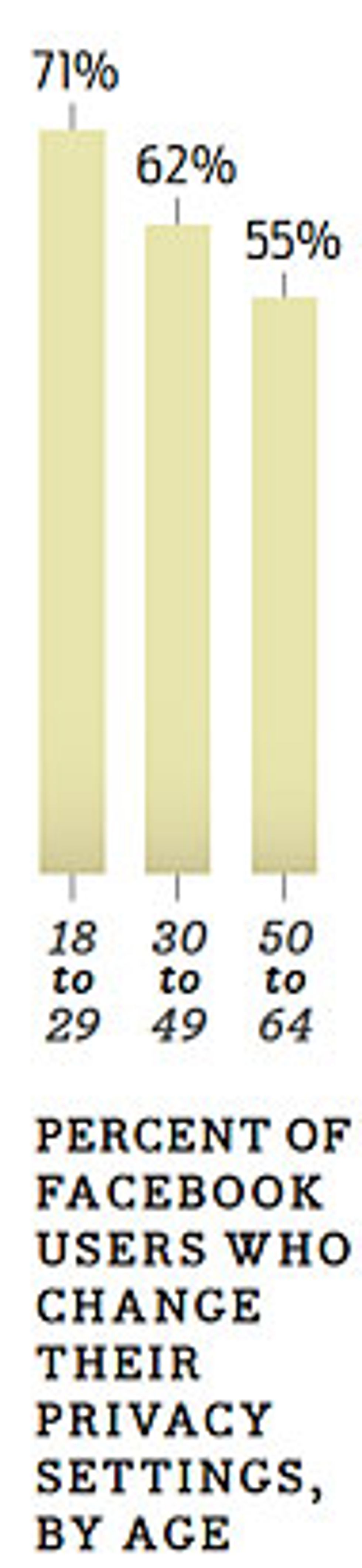

Interestingly, younger people are exerting more control over their online reputations than older people. According to a 2009 survey by the Pew Research Center's Internet and American Life Project, 71 percent of Facebook users aged 18 to 29 reported changing their privacy settings to limit the amount of information they disclose about themselves; only 62 percent of those 30 to 49, and 55 percent of those between the ages of 50 and 64, had done so. It may be that young people care more about control of their privacy than their older peers do, or perhaps they're just more technically literate.

But the kind of control anyone can exert by tweaking privacy settings is minimal. Through a combination of weak policies, poor public discussion, and some remarkable inventions, including social networking services and mobile smartphones with cameras, we have less and less control over our reputations every day. That doesn't mean we want less control. But as long as we are held accountable for youthful indiscretions that potential employers or customs agents can easily google, our opportunities for social, intellectual, and actual mobility are limited. And we are denied second chances.

It doesn't have to be this way.

Each of us learns early on that there are public matters and private matters, and that we manage information differently inside our own homes and outside of them. Yet that distinction fails to capture the true complexity of the privacy tangle, and it has led us astray, for we have come to treat what we do on our personal computers much like what we do inside our homes. But online environments mix up the previously distinct spheres of our relationships, making it easier for employers to track our private lives and stalkers to find out where we work and live. That has to change.

We have to come up with a clearer understanding of the value and meaning of privacy. One way of doing that is by considering a framework of “privacy interfaces”—that is, domains through which we negotiate what is known about us. Each interface offers varying levels of both control and surveillance. If we recognize how these interfaces work in our lives, then we can use services like Google and Facebook with more safety and confidence.

We each have at least four major privacy interfaces. The first is person to peer. Early on we develop the skills necessary to negotiate what our friends and families know of our predilections, preferences, and histories. If we grow up gay in a homophobic family, for instance, we learn to exert as much control over such knowledge as we can. If we as teenagers smoke marijuana in our bedrooms, we learn to hide the evidence from our parents and nosy siblings. If we cheat on our partners, we practice lying. These are all privacy strategies for the most personal spheres.

The second is person to firm. In this interface, we decide whether we wish to answer the checkout clerk at Babies-R-Us when she asks for our home phone numbers. And in this interface we have to think twice about whether to apply for the discount card at the local supermarket or bookstore; while the card will let us purchase items on sale, it will also let the store gather and maintain detailed information about our purchases. When we apply for such a card, though, the clerk almost never explains how the system works or what the true nature of the transaction is.

The third privacy interface is the most important, only because the stakes of misuse and abuse are so high: person to state. Through the census, tax forms, drivers' license records, and myriad other bureaucratic functions, the state has cause to record traces of your movements and activities. The state also has a monopoly on legitimate violence, imprisonment, and deportation, so the cost of being falsely caught in an information dragnet that brings your records to the state's attention is worth considering no matter how unlikely it seems to be.

Until recently, most of us rarely encountered the fourth privacy interface (although Nathaniel Hawthorne explained it well in The Scarlet Letter). It's the person-to-public interface, which the social Web has made the trickiest to negotiate. By now we've all heard of at least one unfortunate event in which some poor soul found his life exposed, his name and face ridiculed, and his well-being harmed by the combination of the rapid proliferation of images, the asocial nature of much “social” Web behavior, and the permanence of the digital record.

Remember the “Star Wars kid”? The high-school student suffered great humiliation after bullies posted a video of him online that showed him playing as if he had a Star Wars light saber. Those bullies ripped the poor kid's image out of context and made him suffer so much his family had to move to another town to escape the harassment.

And how about the woman who became known as “dog-poop girl?” A resident of Seoul, South Korea, she refused to clean up after her dog on the subway, even after fellow riders berated her. Then one of the riders took photos of her and posted them on his blog, and within days others had discovered her name, address, phone numbers, and place of employment. Soon people began harassing her as well as her relatives and friends. Here's a case where massive surveillance by individuals acting as vigilantes can cause harm disproportionate to the offense.

This person-to-public interface is most worrisome because we often have no idea that we're entering it. If a person takes a picture of you at a party in which you appear to be leering at someone (even if you are not actually doing that), you could run afoul of your peers—or your spouse—through no fault of your own. Any of us could have been the Star Wars kid; we all assume comical, fantastic poses when we think we are alone and unwatched. And any of us could fall victim to widespread public shaming or ridicule if untoward videos or images of us leaked onto the Web and traveled the world.

What can we do? In our real social lives we have learned to manage our reputations in various contexts among our friends and family and coworkers. Our domains in real life have enough friction and inconvenience built into them to allow us to shift masks and manage what people know (or think they know) about us.

But the online environments in which we now work and play have been intentionally engineered to simultaneously serve our professional, educational, and personal desires, and so they have broken down the social barriers in our lives. On Facebook or YouTube, a coworker could just as well be a “friend,” fan, or critic. A supervisor could be a stalker. A parent could be a lurker. In such a world, the privacy interfaces blend, and creaky legal distinctions between “public” and “private” places no longer make sense.

Understanding these interfaces and controlling our use of social network sites is only the beginning. Over time, we all must develop social norms that punish bullies who expose private people to ridicule and public humiliation. Beyond that, we should work to establish strong laws that protect the vast majority of us who don't have the skill, time, attention, or awareness to constantly manage our online profiles and multiple reputations. At the very least, companies that make money from harvesting our personal preferences should have to ask us to opt in to these systems of surveillance with all the costs and benefits clearly disclosed. If allowing Facebook and Google the ability to track and store our most personal information will give us better service in return, let's make these companies convince us to enter such a deal. As of now, few of us even comprehend the extent to which we are tracked and studied for the benefit of these companies.

We are just beginning to figure out how to manage our reputations online. And we're making mistakes, lots of them. For some time we will read more stories about employees getting fired over embarrassing Facebook photos or ill-advised tweets. Eventually we will likely develop the social skills and norms to deal with the most absurd and extreme of these situations.

In the meantime the companies that host the online environments will continue to benefit directly from our confusion. The more they know about us, the better they can precisely target both advertisements and content to reflect our expressed interests. It's almost as if they read our minds—because they do. And that means they are not going to make it easy for us to keep our social connections separate from our professional contacts. It's clearly in these companies' interests to scramble everything and see each of us as a single knowable personality. But it's not in our interests. And it's not too late to make the Web more about who we want to be and less about what they want us to be.

This article originally appeared in print as “Welcome to the Surveillance Society.”

This is part of IEEE Spectrum’s special report on the battle for the future of the social Web.

About the Author

Siva Vaidhyanathan has 2611 Facebook friends and 3525 Twitter followers, yet on “The Daily Show” he complained that social network connections are cheap and fleeting. What's more, he values his privacy, as he writes in “Welcome to the Surveillance Society.” He is a professor at the University of Virginia whose latest book, The Googlization of Everything, came out this year.