The U.S. Department of Energy’s high-speed science network is getting a much-needed makeover. When the new 100-gigabit-per-second Energy Sciences Network (ESnet) goes live next month, it will be the world’s fastest continent-spanning science network. But this distinction will probably be temporary: Research networks around the world are in the midst of their own big upgrades.

Now more than ever, science depends on the ability to quickly and reliably move massive amounts of data over great distances. Breakthrough predictions and discoveries, such as climate change and exoplanets, rarely happen at one institution anymore. This summer’s sighting of a particle resembling the Higgs boson, for instance, required sharing about 26 petabytes of data per year among more than 150 computing centers in 36 countries.

The research that ESnet users do is no exception. Traffic over the past decade on ESnet—which connects more than 40 national laboratories, supercomputing centers, and scientific instruments—has been growing at a rate of 72 percent per year, more than twice as fast as the commercial Internet, says director Greg Bell. He expects that growth will accelerate in the coming decade. “[Data] flows generated by the largest science networks and collaborations in the world are seriously stretching the abilities of today’s 10-gigabit networks,” he says.

The upgrade from 10 Gb/s to 100 Gb/s has been a multiyear project. When this generation (the fifth) of ESnet is finally finished, its engineers will have constructed an entirely new network from scratch. “We built the new advanced network in parallel with the existing one, like building a five-lane superhighway next to Main Street,” says Inder Monga, ESnet’s chief technologist.

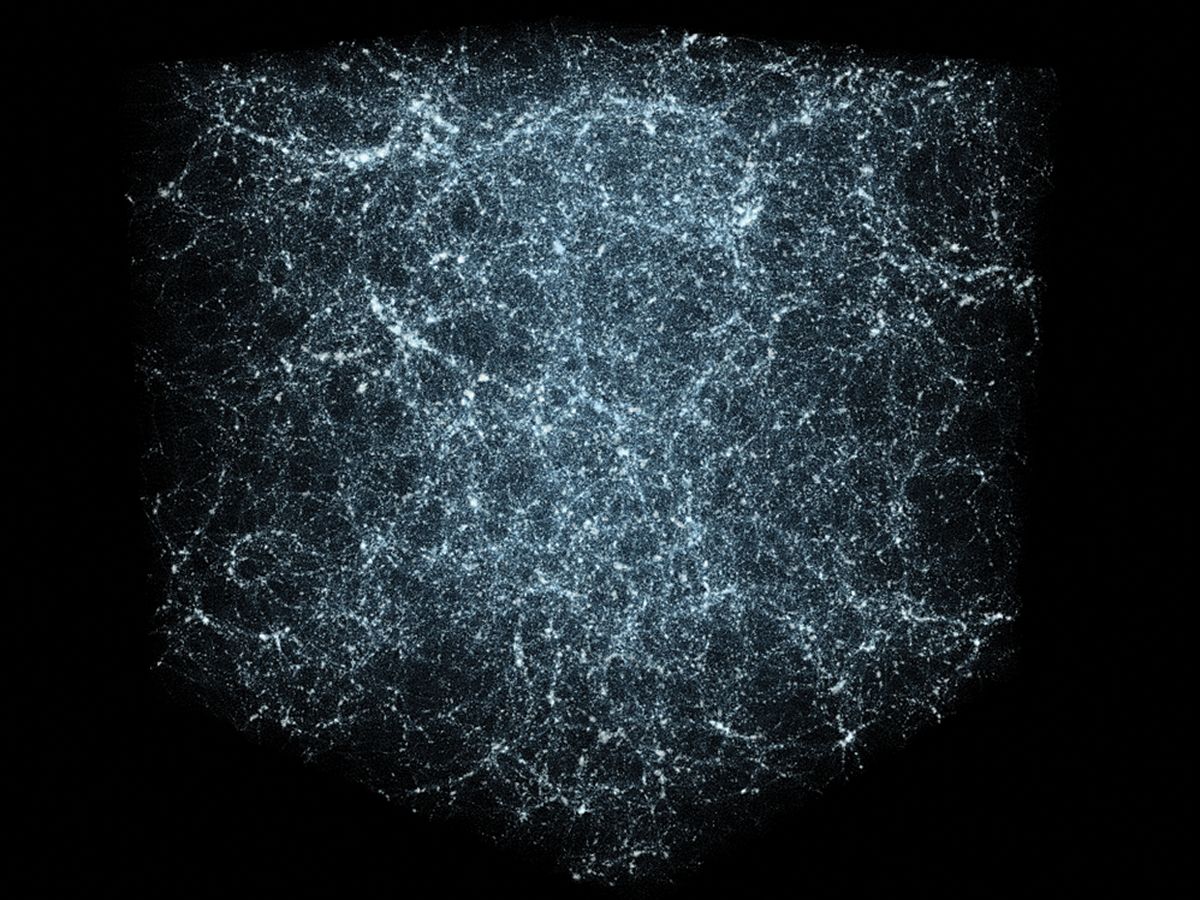

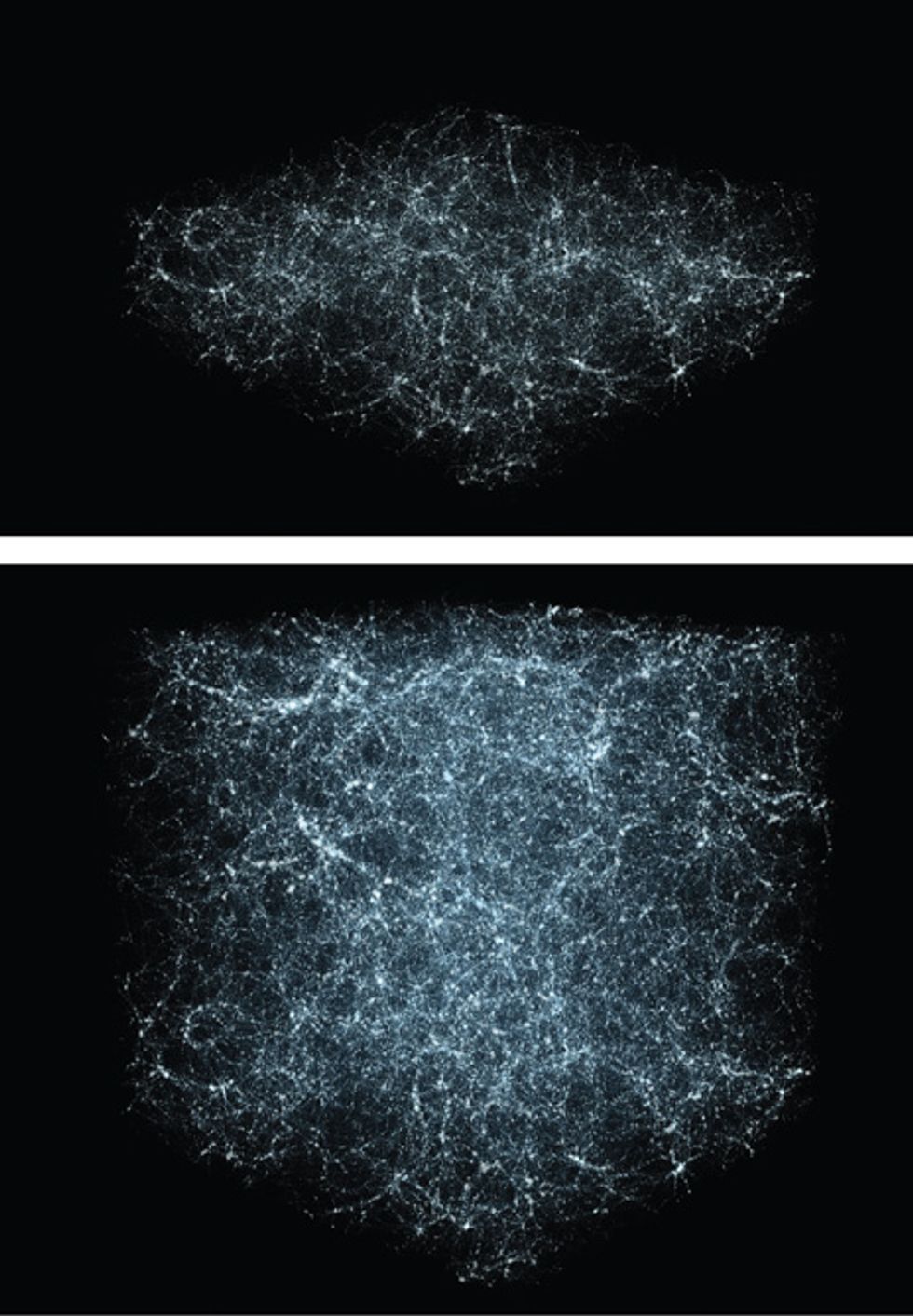

To pave its new information highway, ESnet teamed up with Internet2, a consortium of U.S. universities that operates its own high-bandwidth network. The two agreed to share capacity on dormant (“dark”) optical fibers that Internet2 owns. Left over from the 1990s telecom boom and bust, the fiber web spans the continent, stretching almost 21 000 kilometers if it were laid end to end. Each of its pair of thread-thin fibers can carry up to forty-four 100-Gb/s circuits, which means the shared network could be expanded to transport data at rates up to 8.8 terabits per second.

On top of the dark fiber, ESnet and Internet2 built a layer of optical technology, installing the equipment that receives, transmits, amplifies, regenerates, and combines 100-Gb/s signals. Managing its own optical infrastructure is new to ESnet. In the past, it simply leased additional 10-Gb/s circuits from commercial carriers whenever it needed more capacity. Ownership will allow ESnet to add capacity more cheaply and on its own terms, Bell says.

The last layer of technology ESnet engineers built was the routing layer—the links, hubs, and switches that ensure data packets get where they need to go.

(To reach all its users, ESnet also installed optical and routing technology on an additional 1600 km of fiber that connects centers outside the nationwide backbone it will share with Internet2.)

Engineers are now making last-minute fixes and testing for glitches before opening the network to traffic. Moving users onto the new network will take about a month, Monga says. Soon after, the old 10-Gb/s ESnet will be decommissioned, its hardware returned to ESnet’s laboratory, repurposed for other research labs, or left in place for future expansions or experiments.

Although ESnet will be the first science network to make the switch over to 100 Gb/s, others will soon follow suit. Both China’s and Europe’s research networks have begun the migration, and Internet2 itself plans to finish its full upgrade by next summer.

This article originally appeared in print as "Science at 100 Gigabits Per Second."