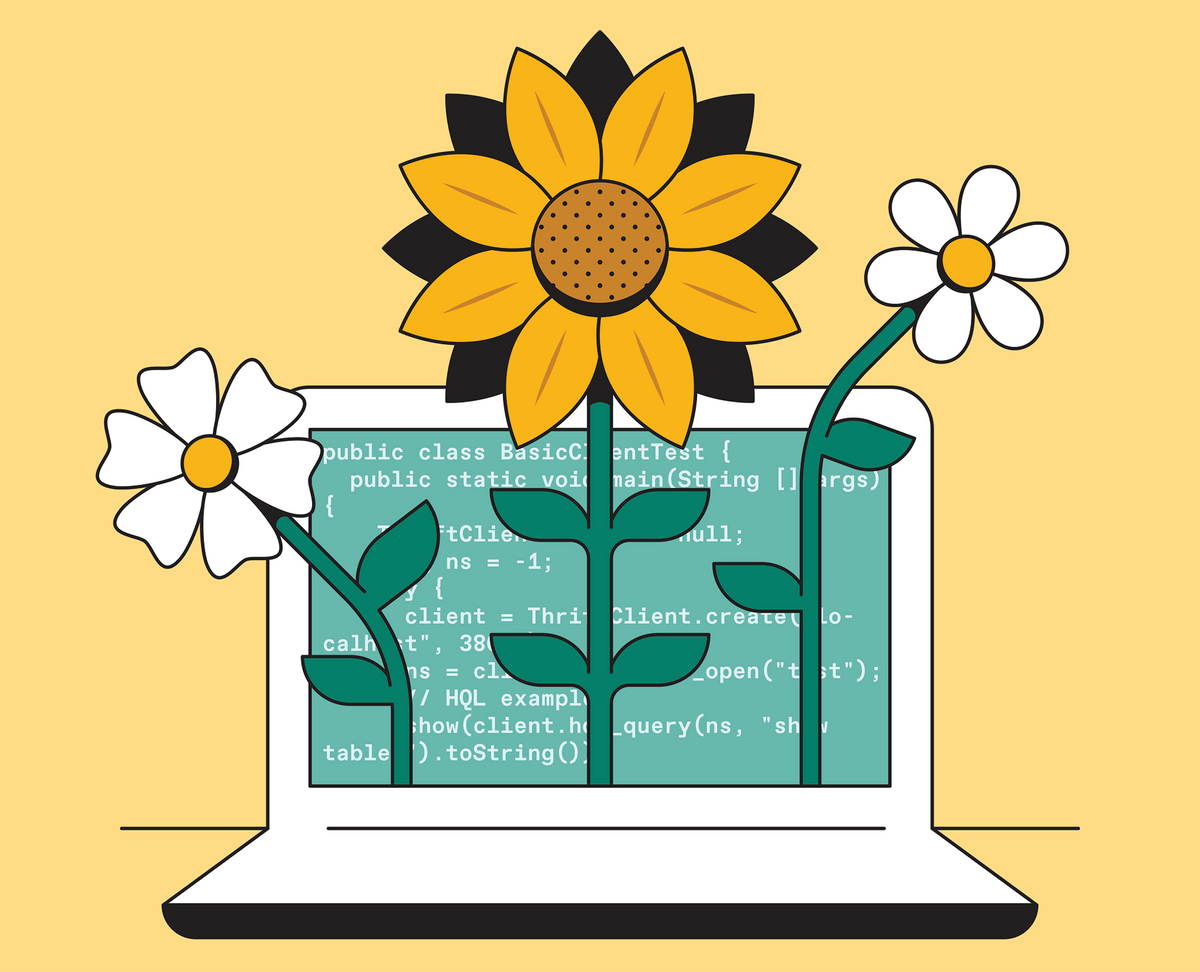

Drug companies are struggling to find ways to legally engage with consumers on social media, reports Nature Biotechnology. There are strict rules about how drug manufacturers can advertise their products, but when it comes to online patient forums and social media comments, things get murky.

For instance, if a patient leaves a comment on a pharmaceutical company’s YouTube video complaining about a rash, does that count as an adverse event that the company must report to federal regulators? What happens when participants in a clinical trial use online forums to share information about their drug’s effectiveness—could that mess up the study?

Guidance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has been variously described as non-existent, unclear, and overbearing, and the uncertainty has forced some drug companies to shy away completely from social media. In fact, half of the 50 largest pharma companies are not actively engaged on social media, according to a report by the IMS Institute of Healthcare Information, Nature Biotechnology reports.

Among the companies that have wandered into the ring, some have gotten themselves into trouble. Zarbee’s Naturals, a dietary supplement manufacturer that sells products for congestion, cough and allergies, got rebuked by the FDA for some of its tweets. Seemingly innocuous messages such as, “Try @Zarbees #naturalremedies for cold and cough season” and “RT@MomCentral have you tried #ZarbeesCough for cold and cough relief?” did not sit well with the FDA. The tweets suggest that the supplements are drugs—a no-no according to federal regulations. The company also caught flak from the agency for how it handled a consumer’s comments on Facebook. Someone posted: “Love Zarbee’s, this is the only medicine we use for our 2 year old. Colds and congestion clear up in 2 days.” Zarbee’s “liked” the comment—also a no-no, according to the warning letter FDA sent to the company.

One of the trickiest areas is “pharmacovigilance”: the rules requiring drug manufacturers to tell the FDA about adverse events—side effects—reported by doctors, patients, or sales reps. “With social media, anybody can publicly complain in just 140 characters,” says Nature Biotechnology. “It’s not yet clear under what circumstances companies are supposed to be monitoring these reports, so many of them are choosing the simplest option: ignore.”

Another tricky area is in clinical trials. Many trials are supposed to be kept blind, meaning that the patients and/or their doctors don’t know if they are getting the drug or the placebo—a practice that prevents bias in the experiment. A couple of years ago, during a phase-two trial for an experimental drug for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), patients unmasked the experiment by talking about their experiences online. Roughly 27 percent of the patients in the trial were active on PatientsLikeMe, an online forum that allows people to share and track their symptoms. When some of them mentioned an unusual side effect called neutropenia, it became obvious which patients had received the active drug.

The FDA released preliminary guidance documents in the summer of 2014 with the aim of clearing things up, but many in the industry say the documents are overbearing and vague, Nature Biotechnology reports. “The guidelines suggest,” says the article, “that products with ‘complex indications or extensive serious risks’ should not be discussed at all in platforms with space limitations, such as Twitter.”

Ten days after the guidance came out, the FDA did a curious thing. One of the agency’s Twitter accounts, @FDA_Drug_Info, tweeted “#FDA approves #Afreeza to treat diabetes” with a link to further information about the drug’s risks. But according to the FDA’s guidelines, it’s own tweet would get a drug company in hot water.

The public comment period on FDA’s guidance documents has ended, but the agency has not given a timeline for when the final versions will be published.

Emily Waltz is a features editor at Spectrum covering power and energy. Prior to joining the staff in January 2024, Emily spent 18 years as a freelance journalist covering biotechnology, primarily for the Nature research journals and Spectrum. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Discover, Outside, and the New York Times. Emily has a master's degree from Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and an undergraduate degree from Vanderbilt University. With every word she writes, Emily strives to say something true and useful. She posts on Twitter/X @EmWaltz and her portfolio can be found on her website.