This week at the IEEE Neural Engineering conference, however, the distinguished neurosurgeon Hugues Duffau argued that information that surgeons gain on the operating table should guide the development of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). “My conclusion is that neurosurgeons are underused,” said Duffau, chair of neurosurgery at Monpellier University in France.

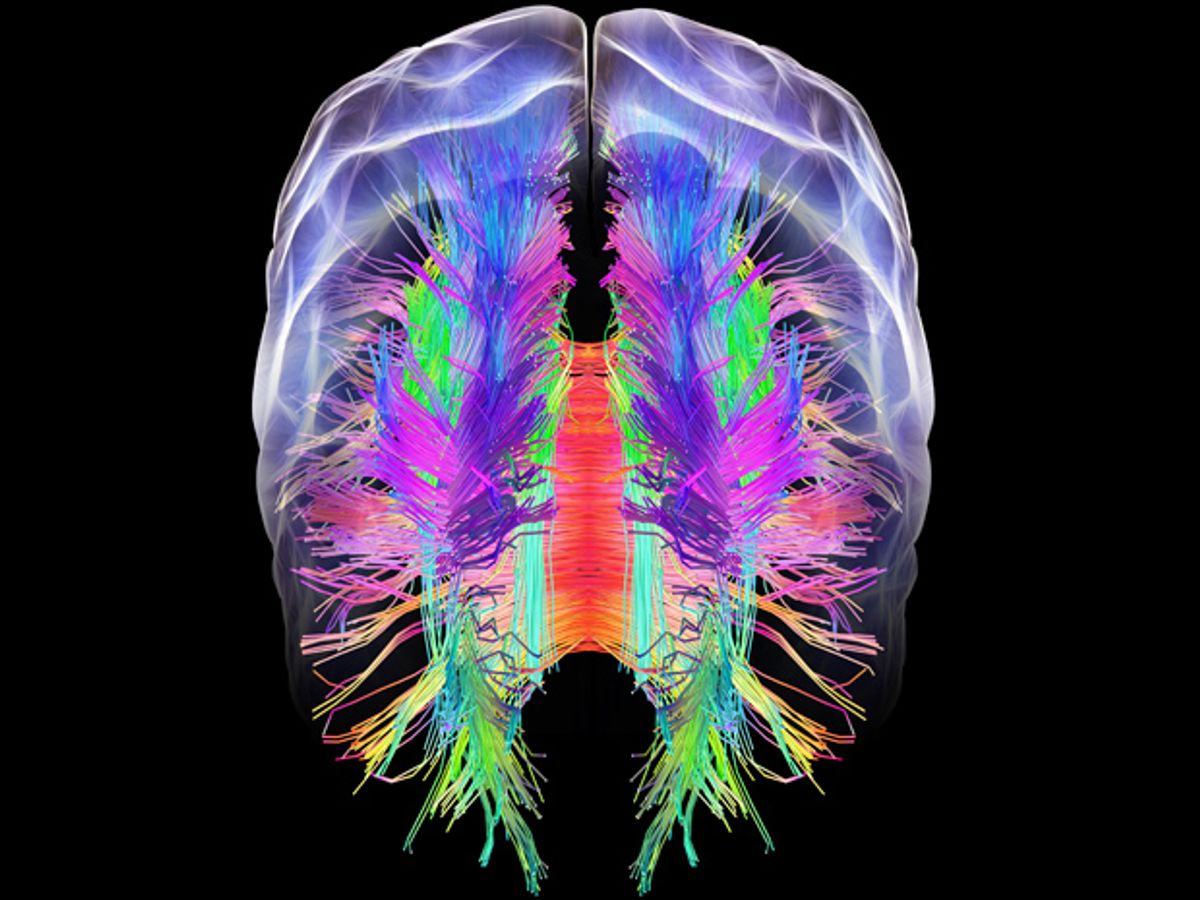

Duffau’s experiences with brain tumor patients have made him a champion of the “connectome,” in which brain functions are understood as the product of circuits in the brain. “You can remove big pieces of the brain and the patient will enjoy a normal life,” Duffau said, thanks to the brain’s remarkable plasticity. “Whereas if we cut pathways, the patient will not recover.”

Major projects are underway to map the connectome, such as the NIH Human Connectome Project launched in 2009 and the even more ambitious U.S. BRAIN Initiative announced by President Barack Obama in 2013, which puts a priority on connectome mapping. Yet despite this growing interest in brain networks, Duffau said, a typical BCI relies on a single implant whose electrodes are inserted in a specific spot. The BCI can then use the neurons in that spot to provide the signal that controls a complex function, such as movement of a robotic limb.

“To me, it’s hard to understand how you can do BCI by putting one electrode in one area that controls movement,” Duffau said, arguing that this approach ignores the way the brain really works. “If you put different electrodes in different parts of the network it will give you more information, and may improve your results,” he said.

Duffau draws further first-hand experience from surgeries to remove brain tumors, during which he uses direct electrical stimulation to map brain functions and ensure (hopefully) that he won’t remove a piece of brain tissue that will disrupt the patient’s life. The patients are awake during this mapping, allowing them to answer questions and perform tasks.

Duffau said his mapping has revealed the failure of the prior model of the brain with functions localized in neat regions. “Localization does not exist,” he said. “It’s not my imagination, it’s what I see every day in the operating room.” He has published scores of papers based on his findings about brain networks, including this useful review article from just a few weeks ago.

For example, our understanding of speech control has been wrong for more than 100 years, Duffau claimed. Famous research done in the 1860s pinpointed speech production to a region named Broca’s area, and further research in the 1870s singled out a region named Wernicke’s area for the ability to understand and produce meaningful speech. But his studies of the connectome, said Duffau, revealed thatBroca’s area is not connected to Wernicke’s area. “The connection does not exist, it was just dogma,” he said. “We believed this dogma for one century.”

Duffau also said his experiences demonstrate the weaknesses of functional MRI imaging (fMRI), which interprets blood flow to brain regions as a proxy of neural activity. As an example, Duffau described a brain tumor patient whose fMRI showed that 90 percent of activation during a language task occurred within the brain’s left hemisphere, with only 10 percent of activation on the right side. Duffau removed a tumor close to that 10 percent area with the expectation that the patient’s language abilities would be unaffected—yet the patient had serious and lasting language problems after the surgery. Take this as a cautionary tale about fMRI, said Duffau. “Of course it’s beautiful, of course it’s non-invasive, but fMRI is not the truth.”

Eliza Strickland is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum, where she covers AI, biomedical engineering, and other topics. She holds a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University.