Careful readers will note that the online versions of six articles from IEEE Spectrum’s January “Top Tech 2015” prediction issue offer them a chance to make their own technology forecasts. At the ends of these articles you’ll find boxes with links to questions on robotics, solar power, the Google Lunar XPrize, exascale computers, drones, and smart cars. These lead to SciCast, the prediction market project co-founded by Charles Twardy, Kathryn Laskey, and Robin Hanson at George Mason University.

SciCast lets participants bet points on specific outcomes of questions in science and technology, testing their judgment against thousands of others’ and reaping rewards if their prognostications are better than those of their competitors. Anyone can browse SciCast to see what participants think the future will bring. And anyone can play. Registration is required to make forecasts and join the game, but it’s minimal and free. You just need to pick a username and password. Even an e-mail address is optional. You may be asked for more information, or to complete a simple questionnaire to gauge general scientific and technical literacy, but whether you respond or not is up to you.

The George Mason team built SciCast with support from the U.S. Intelligence Research Projects Activity. It’s one of tools for staying ahead of world events, political and scientific. SciCast focuses on the sci-tech part, and is one of three approaches that have “produced notable results,” according to the Wall Street Journal.

This kind of competition works because it helps eliminate bias and the kind of herd mentality that can seize small groups of experts. As the Journal went on to say:

Deliberation is useful, but it isn't ideal for generating accurate forecasts: It is susceptible to groupthink. Social biases, such as deferring to those with seniority, intrude on the process. And dissenting views often aren't captured. The effects have led analysts to predict events that didn't occur, or miss events that did take place.

In his best-selling The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail—but Some Don’t, American prognostication guru Nate Silver talked about eliminating bias.

If we want to reduce these biases— we will never be rid of them entirely— we have two fundamental alternatives. One might be thought of as a supply-side approach —creating a market for accurate economic forecasts. The other might be a demand -side alternative: reducing demand for inaccurate and overconfident ones.

A prediction market is the supply-side solution. It lets forecasters work in relative anonymity and isolation, motivated solely by self interest (in theory, at least) as they try to amass the most points. Every bet they make changes the odds: SciCast’s FAQ says that “forecasters spend points to adjust the consensus forecast. Significant changes cost more — but ‘pay’ more if they turn out to be right. So better forecasters gain more points and therefore more influence, improving the accuracy of the system.”

So those out for point-gain and bragging rights can start with these articles, and the associated SciCast questions:

“When Will We Have an Exascale Supercomputer?,” by Jeremy Hsu

- Question 1066. When will an exascale supercomputer appear on the Top 500 list?

- Question 1077. Where will the first exascale computer on the Top 500 list be built?

- Question 1076. What will be the vendor of the first exascale supercomputer on the Top 500 list?

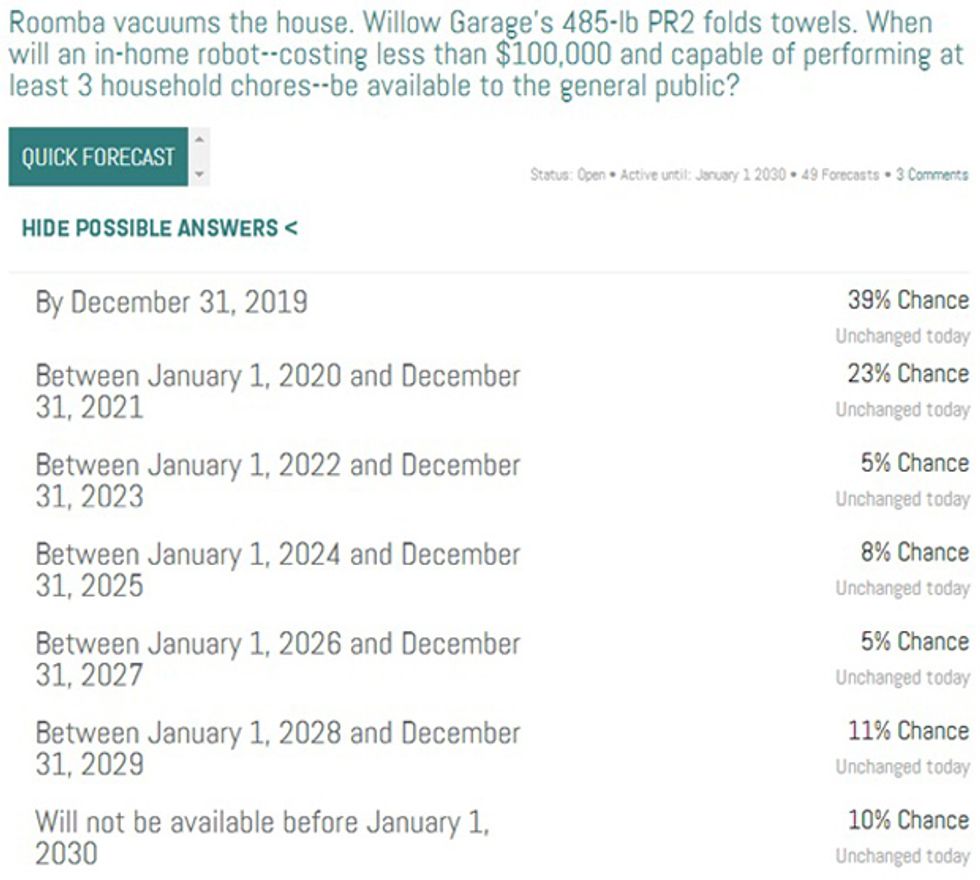

“A Robot in the Family,” by Erico Guizzo

“The XPrize’s Lunar Deadline Drifts,” by Rachel Courtland

- Question 1121. When will a spacecraft land on the Moon and fulfill the requirements of the $20-million Google Lunar XPrize Grand Prize?

- Question 1120. Which of the teams competing as of December 2014 will succeed in claiming the Google Lunar XPrize Grand Prize?

“Big Solar’s Big Surge,” by Peter Fairley

- Question 327. Will California's solar thermal facilities reach an overall capacity of 1.5 GW before the end of 2015?

- Question 450. Will either the US or China have 10 GW in utility-scale PV solar power capacity installed by the end of 2015?

- Question 332. Will a 500 MW capacity solar thermal power station be completed and in operation in the US before the end of 2016?

“Flying Selfie Bots,” by David Schnieder

- Question 105. Will Amazon deliver its first package using an unmanned aerial vehicle by Dec 31 2017?

- Question 553. When will Google or Facebook debut internet connectivity to consumers using solar-powered drones?

“Thus Spoke the Autobahn,” by Philip E. Ross

- Question 900. When will the first car equipped with vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) safety technology be offered for sale to the general public in the US?

- Question 909. When will a car company first debut a production model of a car capable of vehicle to vehicle (V2V) communication and vehicle to infrastructure (V2I) communication?

Douglas McCormick is a freelance science writer and recovering entrepreneur. He has been chief editor of Nature Biotechnology, Pharmaceutical Technology, and Biotechniques.