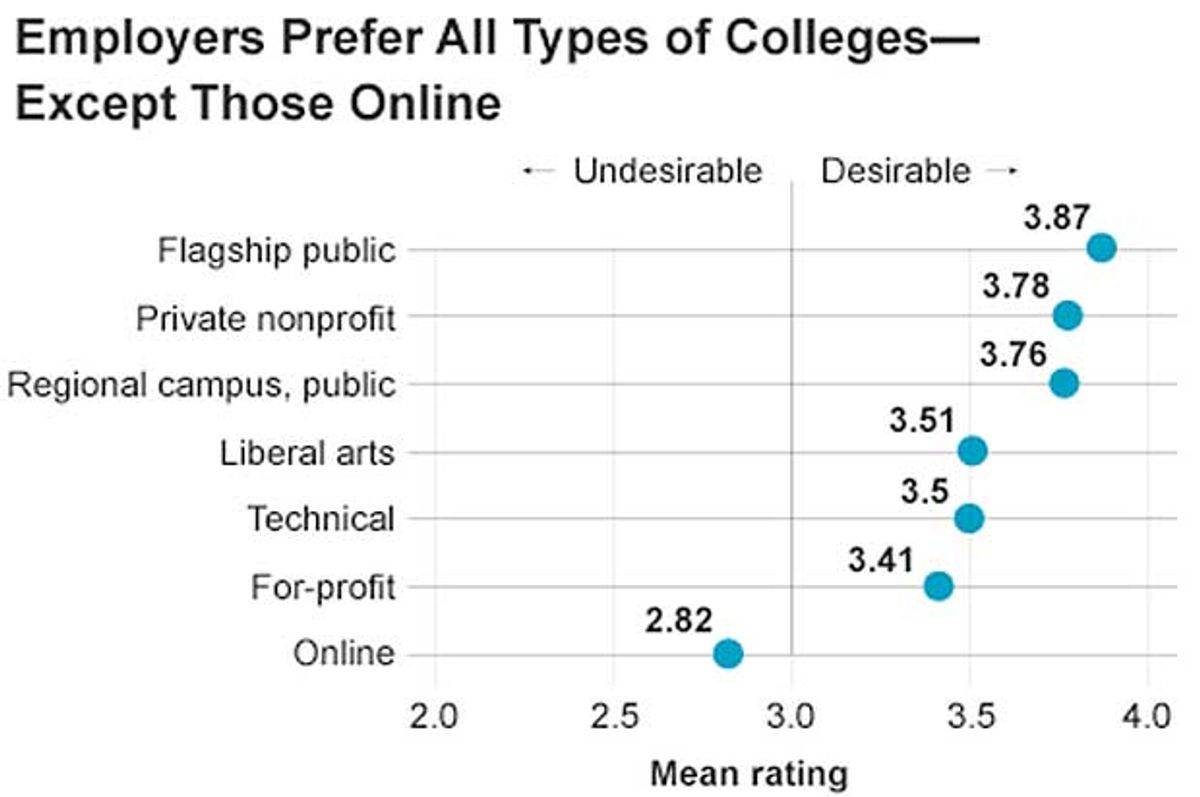

In a 2012 poll of U.S. employers, respondents were asked which types of colleges they preferred to hire from. The results were unambiguous: Company executives and hiring managers considered online colleges inferior to every type of on-campus college. They even preferred for-profit colleges to online colleges, despite the shady track record of many for-profit schools.

The curious thing about the survey is not the result, but the way the question was posed. Executives were asked to evaluate a variety of on-campus programs—“flagship public,” “private non-profit,” and so on. In contrast, only one choice was given for digital education: online. The unstated assumption is that online learning comes in just one flavor—plain vanilla—while on-campus offerings are far richer—caramel fudge swirl, mint chocolate chip, rum raisin, take your pick. Instead of teasing out insightful responses, the question encouraged respondents to fall back on bias.

The creators of that 2012 survey, the Chronicle of Higher Education and the public radio program Marketplace, never followed up with another one. But let’s suppose they did and that in their next survey, the pollsters posed questions as nuanced for online degrees as for on campus. Companies would then be asked to select among online options that reflect the way virtual education is actually offered, with a list of categories comparable to that for on-campus programs—flagship public, private nonprofit, and so on.

Even then, the poll would still be missing one critically important mode of delivering education: blended learning—the pairing of online and in-class approaches within the same program. It’s hard to find a conventional classroom these days that does not have a digital or Web component. It could be a flipped classroom, in which lectures are typically online, and face-to-face discussion is reserved for homework review and projects; online interactions with instructors and classmates; social media; or dozens of other computer- and Web-mediated activities.

That means it’s highly likely that a student graduating this year will have had some sort of virtual experience in pursuit of his or her degree. And so while the employer survey suggested that “online” and “on campus” are distinct from one another, in fact that dichotomy has not existed for at least a decade.

Indeed, for students who receive their diplomas at the most selective schools, the distinction between online and on campus vanishes entirely. Andy DiPaolo, executive director emeritus of Stanford University’s Center for Professional Development, told me: “We never made a distinction between online and on campus. Your degree doesn’t say you earned it online. Students have the option of going online or on campus or taking a blended degree. It’s a Stanford degree.”

Likewise, a degree earned from NYU, University of Michigan, and a number of other schools do not indicate whether it was earned online or on campus. An engineering student who completes her master’s degree online through one of these programs will have the same chances finding a job, getting a raise, or being promoted as she would had she earned her degree on campus. Data from the latest online graduating class at NYU’s Tandon School of Engineering show that nearly three quarters received a promotion or a raise after earning their degree, and all of them were employed six months after graduation.

These results suggest that employers now are more likely to accept job applicants who’ve had an online education. But there are still some hold outs. “We’re in an era of educational transition,” says Amy Lui Abel, managing director of human capital at The Conference Board, a business consulting firm. “Society has not quite accepted the legitimacy of virtual learning. There is still a lot of suspicion. But over the longer term, when a younger generation fills positions at companies, they will be more receptive, unlike older managers who have little familiarity with digital education.”

One 2013 study that looked at the market value of online degrees confirms Abel’s insight. It concluded that an employer’s attitude toward online education tends to be more positive if he or she has had some personal experience with online learning. “As more people attend online schools over time and the number of graduates sitting on the hiring side of the desk increases, we can anticipate more favorable treatment of online university graduates,” the study’s authors noted.

And so in comparing and contrasting online to on-campus degrees, it’s important to tease out and appreciate the differences. The results shown in the graph above are suspect, because they do not reflect the real world of higher education today. Imagine if the survey respondents had been asked instead: “Would you prefer to hire graduates who earned their degrees online at Stanford or on campus at Fly-By-Night University?” In this absurd choice, online would of course beat on campus hands down.

About the Author:

Robert Ubell is Vice Dean Emeritus of Online Learning at NYU’s Tandon School of Engineering. A collection of his essays on digital education, Going Online: Perspectives on Digital Learning, was recently published by Routledge. He can be reached at bobubell@gmail.com. This is the third in a series on MOOCs and online learning.