New technology may help to bring dead satellites back to life. Earlier this year, the Mission Extension Vehicle (MEV), a spacecraft jointly managed by NASA and Northrop Grumman, made history when it resurrected a decrepit satellite from the satellite graveyard. Reviving the spacecraft is a key step in extending the lifetime of orbiting objects; a second mission is set to extend the lifetime of another satellite later this summer.

Most satellites in geosynchronous orbits (GEO) have a design life of 15 years and are launched with enough fuel to cover that timeframe. At the end of their lifetime, the crafts are required to enter a graveyard orbit mandated by the 2002 draft Mitigation Guidelines issued by the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC). Graveyard orbits comprise paths at least 300 kilometers above the geosynchronous region, giving the zombie spacecraft room to have their orbits incrementally ground down by the gravity of the sun and moon.

Even when they're out of fuel, most satellites are still fully capable of functioning. “The technical degradation—besides fuel—of the satellite subsystems beyond 15 years is very marginal,” says Joe Anderson, vice president of business development and operations at SpaceLogistics, a subsidiary of Northrop Grumman. Anderson says he's aware of satellites providing valuable services for nearly 30 years.

Defunct satellites are tracked primarily by the United States Air Force, which follows their mass rather than their radio signals. Smaller bits such as debris are difficult for the Air Force to follow, but satellites are usually large enough (though new technology is bringing them down in size). In contrast, the IADC is comprises just over a dozen space agencies and is the "gold standard" in space recommendations, says Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

According to McDowell, who is also author of Jonathan's Space Report, a weekly newsletter cataloguing the comings and goings of spacecraft, there are 915 objects within 200 km of the GEO, so they still have plenty of room to avoid one another. The looming issue is the 365 defunct spacecraft that—due to malfunction, lack of planning, or laziness—didn't follow the IADC's guidelines. In contrast, the graveyard region contains only 283 spacecraft. Dead satellites not parked in the agreed upon spot could lead to collisions (and therefore more debris) which could damage active spacecraft.

“The level of compliance is a little disappointing,” McDowell says. “The junk satellite environment close to GEO is more than one would want.”

In February, MEV-1 successfully brought a zombie satellite back from the graveyard back into geostationary orbit, where it now serves over 30 customers. Launched in 2001, the satellite eventually ran out of fuel and retired to the satellite graveyard. Without fuel, it could no longer adjust its orbit, though its other systems remained functional.

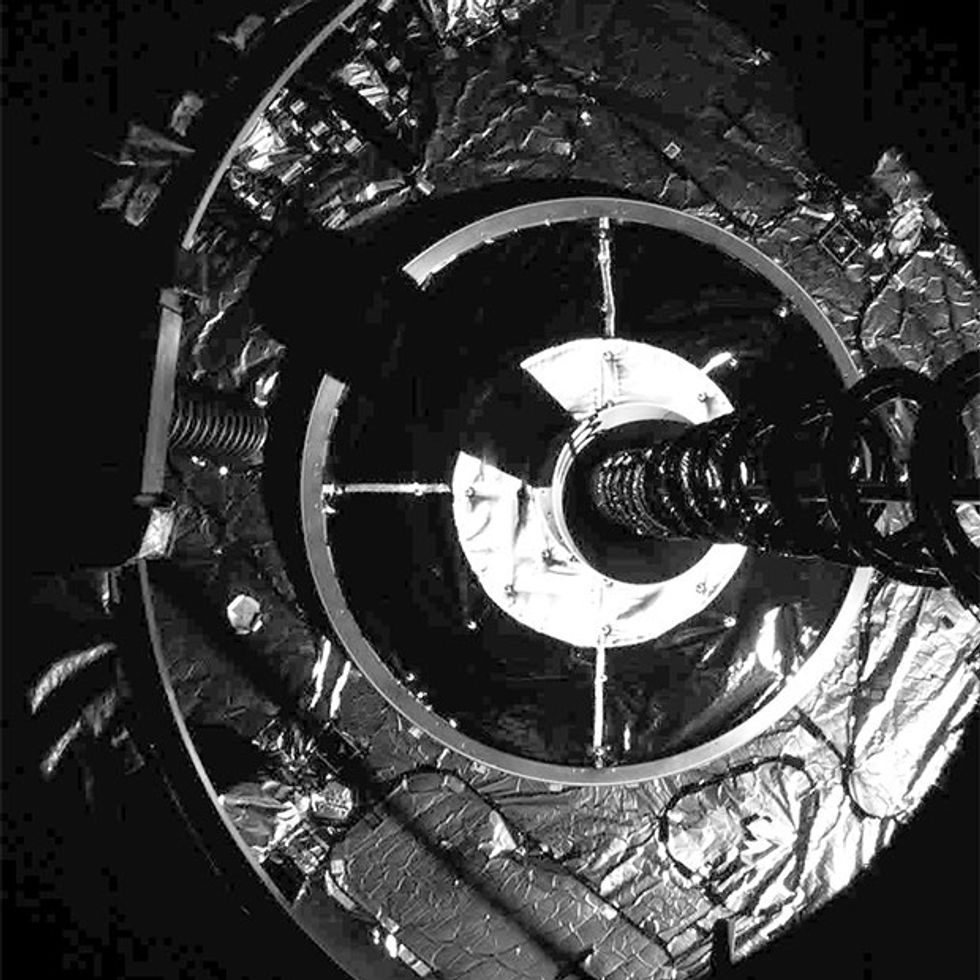

The MEV-1 was designed for interfacing with single-use satellites like the zombie satellite. By docking with the satellite's liquid apogee engine, a common feature that helps most geostationary satellites finalize their orbits at the start of their lifetime, MER-1 captured the satellite and began to lower its orbit, putting the dead satellite back into play at the start of April. MEV-1 will remain connected to the Intelsat for the next five years, then return it to the graveyard. MEV-1 will then proceed to its next customer.

MEV-1 is only the beginning. Anderson says that a second MEV will be launched later this summer. It will reach geostationary orbit in January 2021 and extend the lifetime of a second Intel satellite for an additional five years. Northrop Grumman plans to have only two MEVs in space, but Anderson expects them to be utilized throughout their 15-year-plus lifetime. The company is also developing Mission Extension Pods, smaller propulsion augmentation devices installed on a client's satellite to provide orbital boosts, extending missions for up to six years. The first pods should launch in 2023, Anderson says.

While Northrop Grumman touts refueling and refurbishing missions like MEV as a bonus to the company's bottom line, McDowell sees it as a great way to solve the growing problem of space debris and the collection of defunct human-made objects in space. Spacecraft like the MEV could potentially relocate nonfunctioning satellites from GEO to the graveyard, though there are likely to be regulatory and legal issues over who has the right to haul away someone else's trash. He has long advocated for a launch tax on the companies using space; those funds would sustain an “international space garbage trucking agency” responsible for cleaning up the messes from collisions and enforcing the removal of out-of-work satellites.

“The era of the space garbage truck is coming,” McDowell says.

Editor’s note: Corrected spelling of Northop Grumman 19 June 2020.

A version of this post appears in the August 2020 print issue as “Bringing Satellites Back From the Dead.”