Swarm Wants to Send Hundreds of Tiny CubeSats Into Orbit

A notorious startup asks FCC for permission to launch a 150-strong constellation of small IoT satellites

A day after being whacked with a US $900,000 FCC fine for launching four tiny CubeSats without permission, Silicon Valley startup Swarm Technologies sought permission for dozens more of its controversial small satellites, according to documents obtained by IEEE Spectrum.

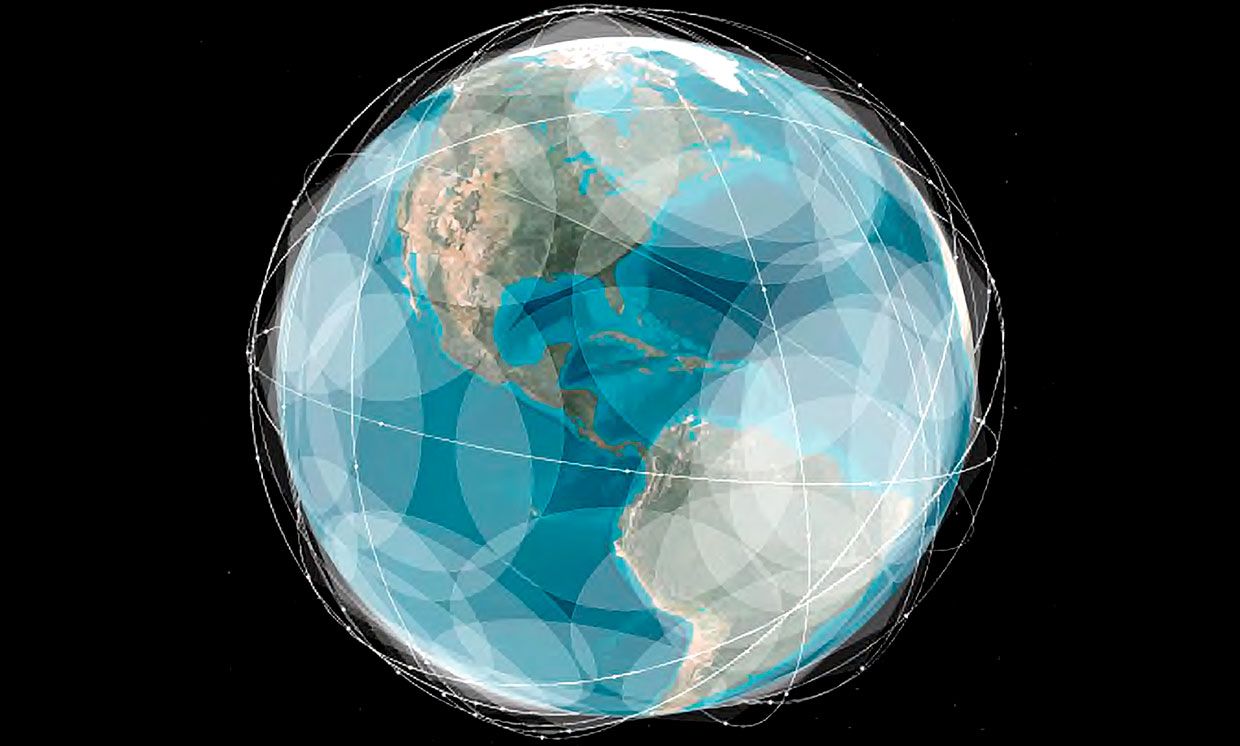

Swarm wants to create an orbital network of miniature satellites that will offer a global Internet of Things communication service at a fraction of the price of existing systems.

“Swarm will offer two-way communications services to allow end users to send and receive data anywhere in the world,” reads its latest FCC application. “The Swarm constellation will be deployed rapidly, and begin to offer commercial services even prior to full deployment of the constellation.”

Swarm told the FCC that it could start launching its innovative satellites—which measure less than 3 centimeters on their smallest edge and weigh about the same as a can of soup—as soon as March 1. It hopes to have a full constellation of 150 operating in low Earth orbit by the end of 2019.

Because the satellites are so small and light, they can be built and launched much more quickly and cheaply than traditional satellites. Each 1/4U (11- x 11- x 2.8-centimeter) Swarm CubeSat weighs about one-thousandth as much as the broadband Internet satellites proposed for SpaceX’sStarlink constellation, for example.

But Swarm’s diminutive satellites have raised red flags at the FCC in the past. The agency refused permission for four experimental 1/4U Swarm satellites called SpaceBEE in 2017, worrying that such tiny objects would be difficult to detect from the ground.

“In the absence of tracking at the same level as available for [1U] objects… the ability of operational spacecraft to reliably assess the need for and plan effective collision avoidance maneuvers will be reduced or eliminated,” wrote the chief of the FCC’s Experimental Licensing Branch at the time.

Swarm went ahead and launched anyway in January 2018. This was the first time satellites had ever been launched illegally, as IEEE Spectrum was the first to report. The FCC was furious, revoking permission for future Swarm launches and launching an investigation, which discovered that Swarm had also carried out unauthorized tests of its technology in a Silicon Valley garage, and even used weather balloons to transmit data to moving cars.

On December 20, 2018, the FCC issued a consent decree that levied a $900,000 fine on the young company and implemented a compliance plan to prevent future wrongdoing.

The very next day, Swarm asked the FCC permission to launch and operate a constellation of 150 satellites almost identical to the ones that caused so much trouble before.

At first glance, the new constellation might look even riskier than the experimental CubeSats the FCC barred. While there were only four devices in the original application, this one would see more than 500 satellites being launched into orbit over the constellation’s 15-year lifetime. This is because there are still wisps of atmosphere at Swarm’s chosen altitudes of between 450 and 550 kilometers, dragging down the CubeSats to burn up in as little as two and a half years.

On the way down, each satellite would also pass through the 400-kilometer band where the International Space Station orbits. At the lowest altitude of 450 km, Swarm’s satellites would have to be replaced at least four times over the 15 years.

However, Swarm’s new application goes to great lengths to persuade the FCC that its tiny satellites are much less dangerous than the agency first thought. For a start, being so small and light, they are virtually guaranteed to burn up completely in the atmosphere, thus posing no risk to people on Earth (unlike SpaceX’s satellites).

Second, the satellites will carry radar retroreflectors, developed at the federal Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center, in San Diego, to boost their visibility to ground-based stations. Similar reflectors fitted to the illegally launched SpaceBEEs have shown that they are at least as visible as some larger 1/2U and 1U satellites in similar orbits.

A study by the space tracking firm LeoLabs (paid for by Swarm) found that the SpaceBEEs could be detected more than once a day on average, which was better than some larger satellites. Swarm has also contracted with LeoLabs to track its new constellation and provide a second source of orbital data to supplement the U.S. government’s Space Surveillance Network. A GPS chip will also regularly beam the satellite’s position down to Swarm HQ.

Despite being tiny and lacking propulsion, the satellites also have some modest maneuvering capability. Onboard magnetorquers will allow them to shift from a low-drag to a high-drag state, accelerating their descent. Swarm says it will instruct satellites to go into their high-drag configuration when they near the ISS, thus minimizing the time they spend at its altitude.

Swarm’s application does not spell out how its communications services will work, except to note that there will not be any intersatellite links. This means that each satellite will be able to connect to the Internet briefly only once it is over any future ground stations. There is likely to be a delay of many minutes, at least, between a user or device sending data up to the satellite and being able to receive a reply.

That rules out streaming data or voice services, but it opens the door to less time-sensitive IoT applications in agriculture, asset tracking, and remote diagnostics. “Swarm-based satellite services will also support text message platforms that can connect individuals in locations without cellular or Wi-Fi coverage,” reads the application. Swarm says it will provide low-cost connectivity to nonprofits and humanitarian organizations, as well as enabling border patrol and homeland security applications.

The company also told the FCC that it was working with “a top automaker and other transportation companies to address connectivity solutions for connected cars, trucking, and fleet monitoring,” as well as two U.S.-based Fortune 100 companies.

The filings reveal that the company is backed by troubled Silicon Valley venture capital firm Social Capital, and by Sky Dayton, founder of Internet service providers EarthLink and Boingo Wireless.

Although Swarm’s constellation will necessarily orbit above most parts of the globe, the current FCC application is only for a U.S. service. Expanding abroad might prove problematic, as the radio frequencies that Swarm’s satellites use for listening to ground stations (137–138 megahertz for downlink and 148–149.5 MHz for uplink) are already being used by rival satellite IoT startups in Europe, and possibly elsewhere.

Commercial concerns aside, Swarm’s real test in the next few months will be to convince the FCC that the company’s big mistakes in the past should not prevent its small satellites from having a future.

Mark Harris is an investigative science and technology reporter based in Seattle, with a particular interest in robotics, transportation, green technologies, and medical devices. He’s on Twitter at @meharris and email at mark(at)meharris(dot)com. Email or DM for Signal number for sensitive/encrypted messaging.