Contributions to U.S. Election Campaigns

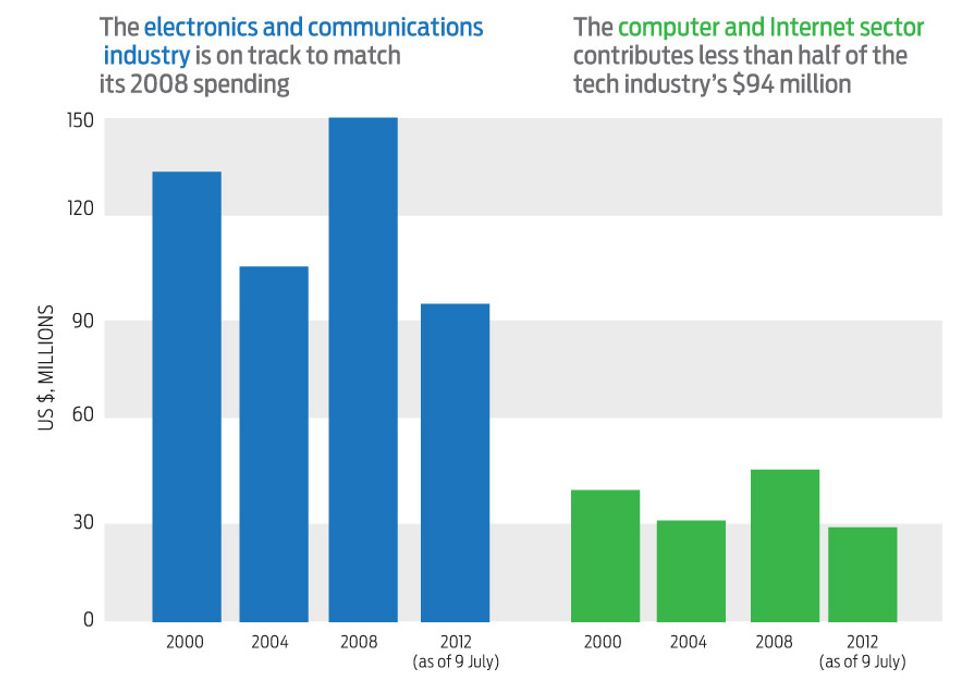

When it comes to funding political campaigns, the technology industry maintains a pretty low profile. In fact, figures from the Center for Responsive Politics (CRP) show the industry is spending about the same amount as in previous presidential election years [see chart, "Contributions to U.S. Election Campaigns"]. That’s despite overall campaign spending that’s set to beat 2008’s record by US $400 million.

As of the end of July, numbers tallied by the CRP showed that contributors from the electronics and communications category (which includes computer and Internet companies) had spent $94 million. Following historical giving patterns, that put the category on pace to match total 2008 spending of $149 million. “Contributions tend to peak close to the election—that’s when you typically see the most money flowing into the system,” says Douglas H. Weber, a senior researcher at the CRP.

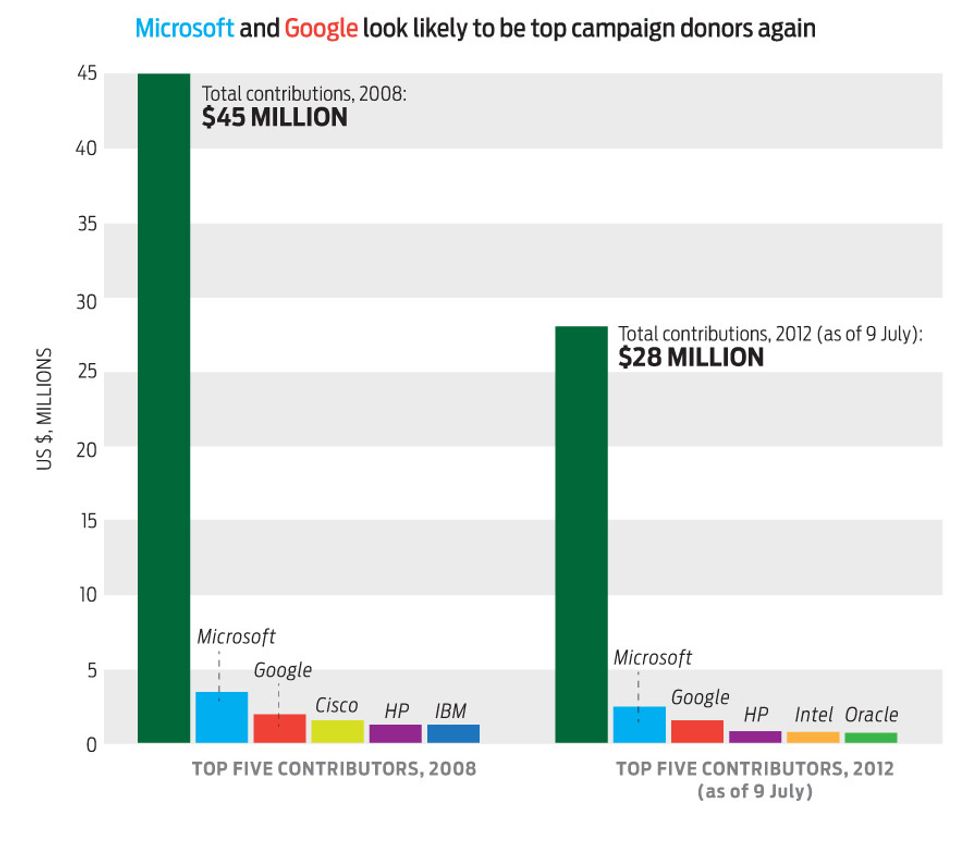

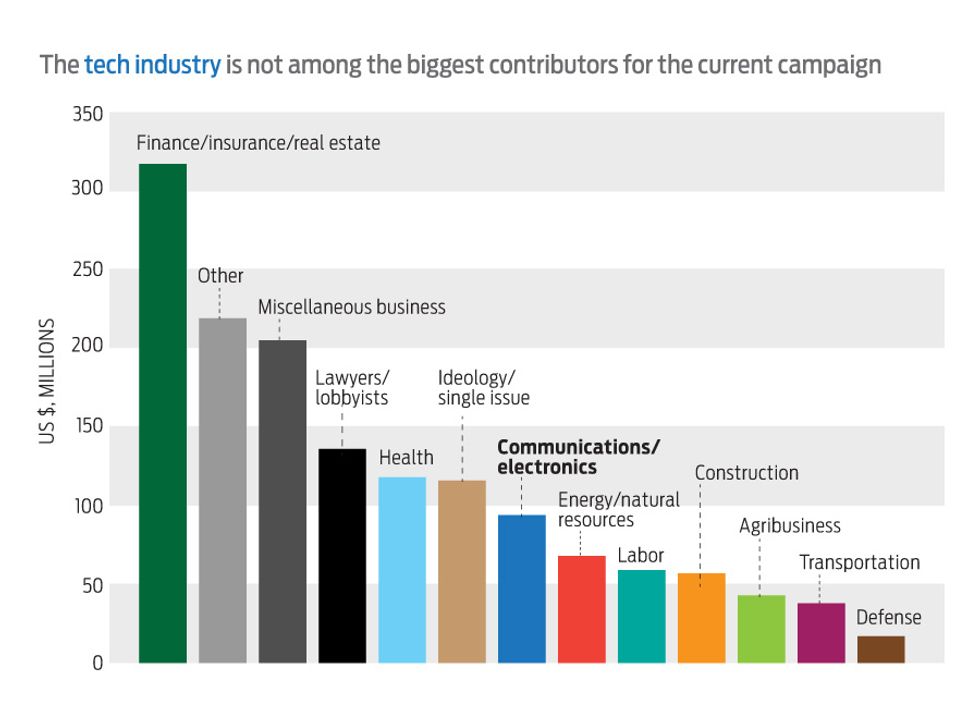

Ever since the watershed year of 2000, the end of a decade in which the Microsoft antitrust trial showed the tech industry that it needed to pay attention to Washington, Silicon Valley has been experimenting with ways of flexing its political muscle. Yet it still doesn’t give nearly as much money as other industries, such as finance and banking, and legal.

Betsy Mullins, senior vice president for policy and political affairs at the tech industry advocacy group TechNet, says the industry is still in its adolescence when it comes to political giving. “Over time, this unregulated industry gradually bumped into more issues and realized it needed stronger relationships in D.C.,” she says. Even though tech companies have risen in the Fortune 500 (Google is currently ranked 73), their political giving pales in comparison to some of their peers on that list, she says. “Banks and telecommunications companies have political giving and lobbying down to an art form, because they’ve been doing it for 100 years,” she says.

At the same time, the shifting rules in campaign finance make it hard to be certain exactly how much the tech industry—or any industry—is giving and how. “Our suspicion is that there may be a lot of money that we’re not seeing, that’s following a different pattern,” says Bill Allison, editorial director at the government watchdog group Sunlight Foundation. “But unfortunately we can’t say with any certainty because we just don’t know who the donors are.”

Those shifting rules have changed and will probably continue to change how companies give. “All of these variables are still shaking themselves out,” says Mullins. “I think in four years you’re going to see a very different type of political activity than what the tech community is doing today. I can’t predict what that’s going to be, but all these factors influence what tech does in the political space.”

Already, tech companies are exploring giving more than just money, such as offering free training. “Facebook and Twitter both have active efforts to recruit members of Congress to use their platforms to communicate with their constituents,” says Allison. “That’s not necessarily a campaign contribution or a lobbying campaign, but clearly it’s an attempt to both sell their services and to get members of Congress to have a good impression of them.”