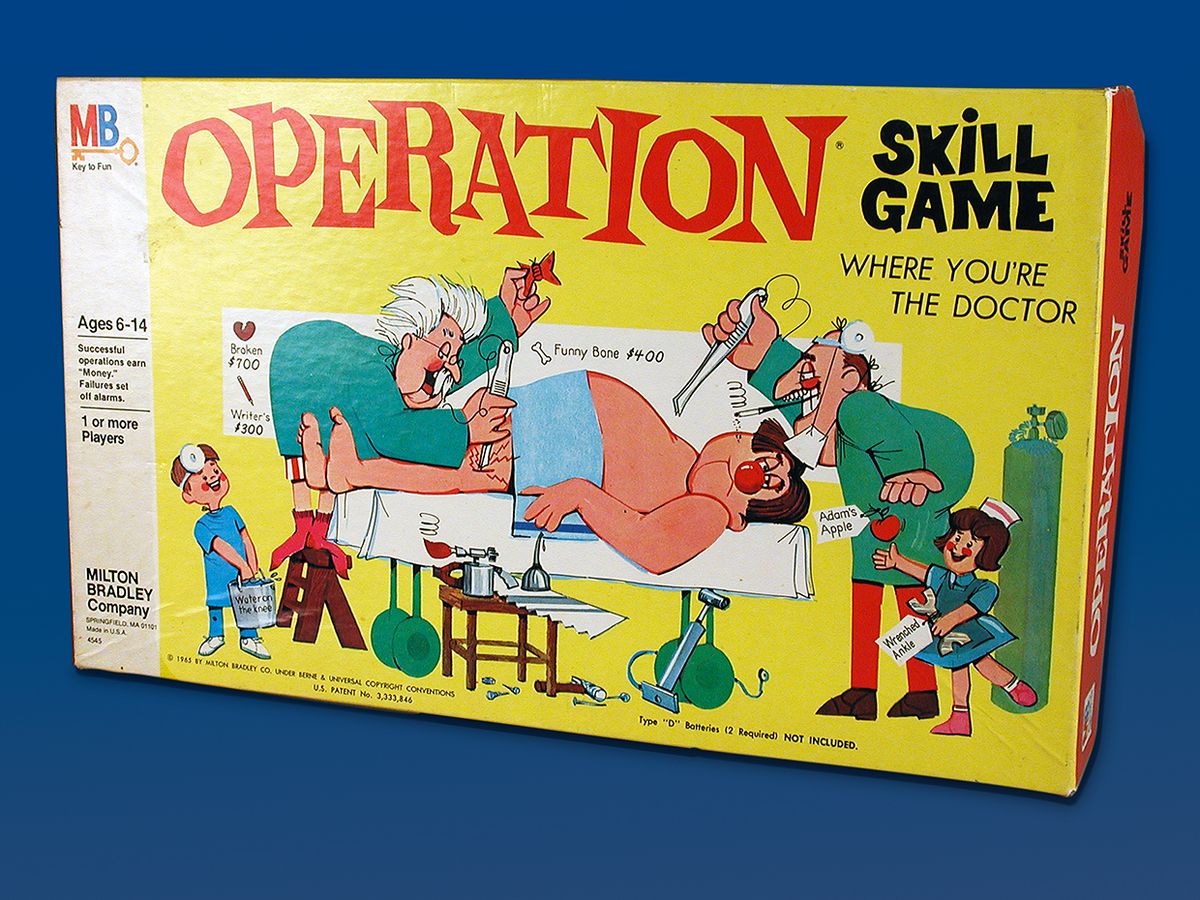

Cavity Sam, the cartoon patient in the board game Operation, suffers from an array of anatomically questionable ailments: writer’s cramp (represented by a tiny plastic pencil), water on the knee (a bucket of water), butterflies in the stomach (you get the idea). Each player takes a turn as Sam’s doctor, using a pair of tweezers to try to remove the plastic piece for each ailment. Dexterity is key. If the tweezers touch the side of the opening, it closes a circuit, causing the red bulb that is Sam’s nose to light up and a buzzer to sound. Your turn is then over. The game’s main flaw, at least from the patient’s perspective, is that it’s more fun to lose your turn than to play perfectly.

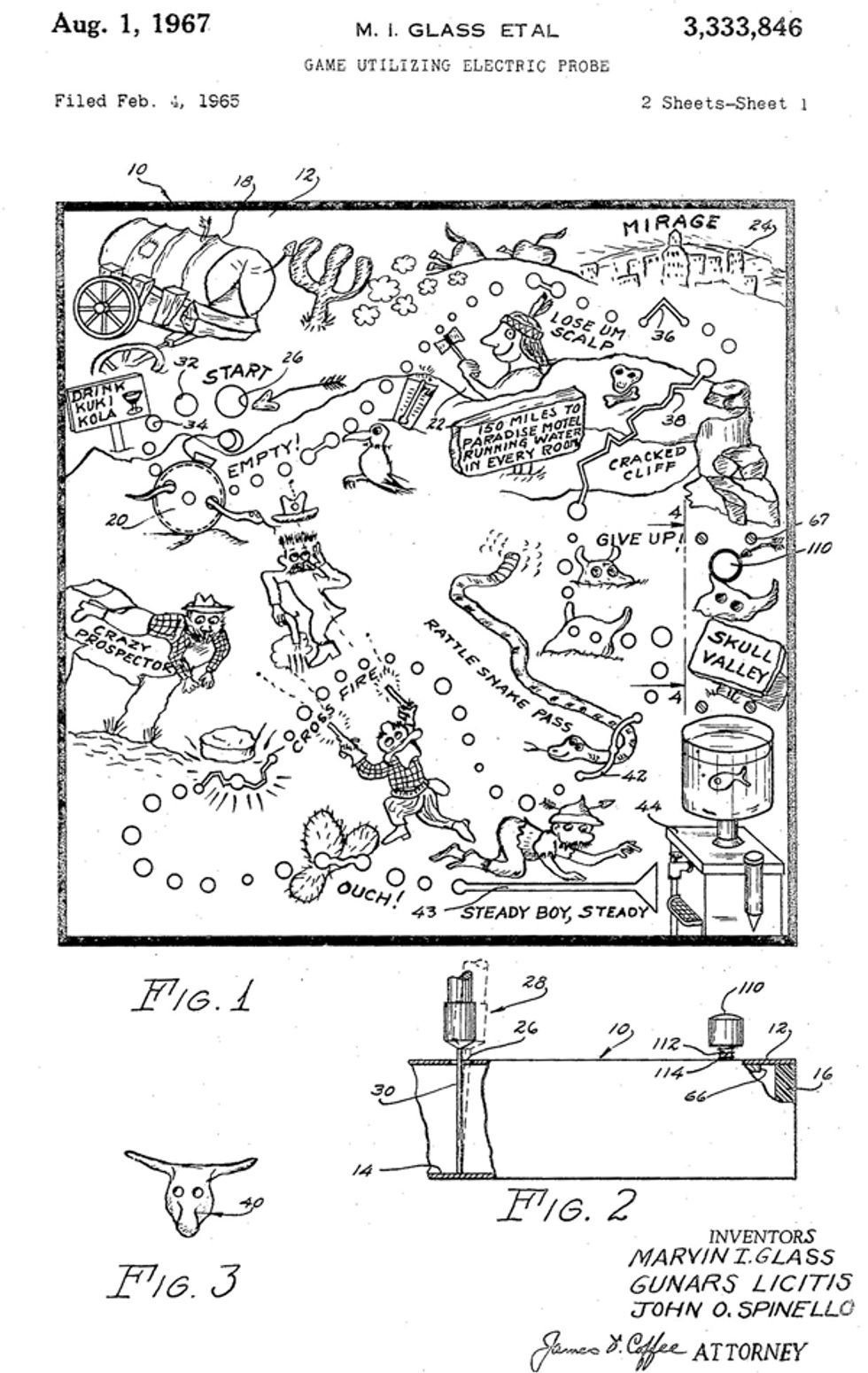

John Spinello created the initial concept for what became Operation in the early 1960s, when he was an industrial design student at the University of Illinois. Spinello’s game, called Death Valley, didn’t feature a patient, but rather a character lost in the desert. His canteen drained by a bullet hole, he wanders through ridiculous hazards in search of water. Players moved around the board, inserting their game piece—a metal probe—into holes of various sizes. The probe had to go in cleanly without touching the sides; otherwise it would complete a circuit and sound a buzzer. Spinello’s professor gave him an A.

Spinello sold the idea to Marvin Glass and Associates, a Chicago-based toy design company, for US $500, his name on the U.S. patent (3,333,846), and the promise of a job, which never materialized.

Mel Taft, a game designer at Milton Bradley, saw a prototype of Death Valley and thought it had potential. His team tinkered with the idea but decided it would be more interesting if the players had to remove an object rather than insert a probe. They created a surgery-themed game, and Operation was born.

The game debuted in 1965, and the English-language version has remained virtually the same for decades. (A 2013 attempt to make Cavity Sam thinner and younger and the game pieces larger and easier to extract did not go over well with fans.) Variations of Operation have featured cartoon characters other than Cavity Sam, such as Homer Simpson, from whose body the player extracted donuts and pretzels, and Star Wars’ Chewbacca, who’s been infested with Porgs and other “hair hazards.” International editions are available in French, German, Italian, and Portuguese/Spanish. The global franchise for all this electrified silliness has generated an estimated $40 million in sales over the years.

Such complete-the-circuit games actually date back to the mid-1700s. Benjamin Franklin designed a game called Treason, which involved removing a gilt crown from a picture of King George II without touching the frame. And in a popular carnival game, contestants had to guide an electrified wire loop along a twisted rod without touching it.

Spinello was not the first to patent such a game. In 1957, Walter Goldfinger and Seymour Beckler received U.S. patent 2,808,263 for a portable electric game that simulated a golf course and its hazards. They in turn cited John Braund’s 1950 patent for a simulated baseball game and John Archer Smith and Victor Merrow’s 1946 patent for a game involving steering vehicles around a board.

A few years after Spinello filed for his U.S. patent, but two months before it was granted, an inventor named Narayan Patel filed for a remarkably similar game that also called for inserting a metal probe between electrified plates. Patel outlined four themed games based on this setup, one of which was aimed at adult partiers. He called his amusement and dexterity test “How Much Do You Drink?” with ranges from “Never heard of alcohol” to “Brother, you are dead.”

But if your main goal was to get inebriated while testing your fine motor skills, you didn’t really need a dedicated game. Some players simply adapted their own drinking rules to Operation. Needless to say, if you didn’t start the game with the skilled hands of a surgeon, it is unlikely that a few alcoholic beverages would help.

An abridged version of this article appears in the December 2019 print issue as “A Game With Buzz.”

Part of a continuing serieslooking at photographs of historical artifacts that embrace the boundless potential of technology.

About the Author

Allison Marsh is an associate professor of history at the University of South Carolina and codirector of the university’s Ann Johnson Institute for Science, Technology & Society.