The Ferranti Mark 1 was the first commercially available general-purpose computer. The one shown in this 1955 photo—a slightly improved model known as the Ferranti Mark 1*—was used to help forecast election results, calculate wages, and produce actuarial tables, among other things.

Based on the Manchester Mark 1 and built by Ferranti Ltd., the huge machine was housed in two spacious bays, each 5 meters long, 2.4 meters high, and 1 meter wide, with a control desk at one end. Inside were 4,000 electronic valves (or vacuum tubes), 2,500 capacitors, 15,000 resistors, and nearly 10 kilometers of wiring. It consumed 27 kilowatts of power and operated at a base clock frequency of 100 kilohertz.

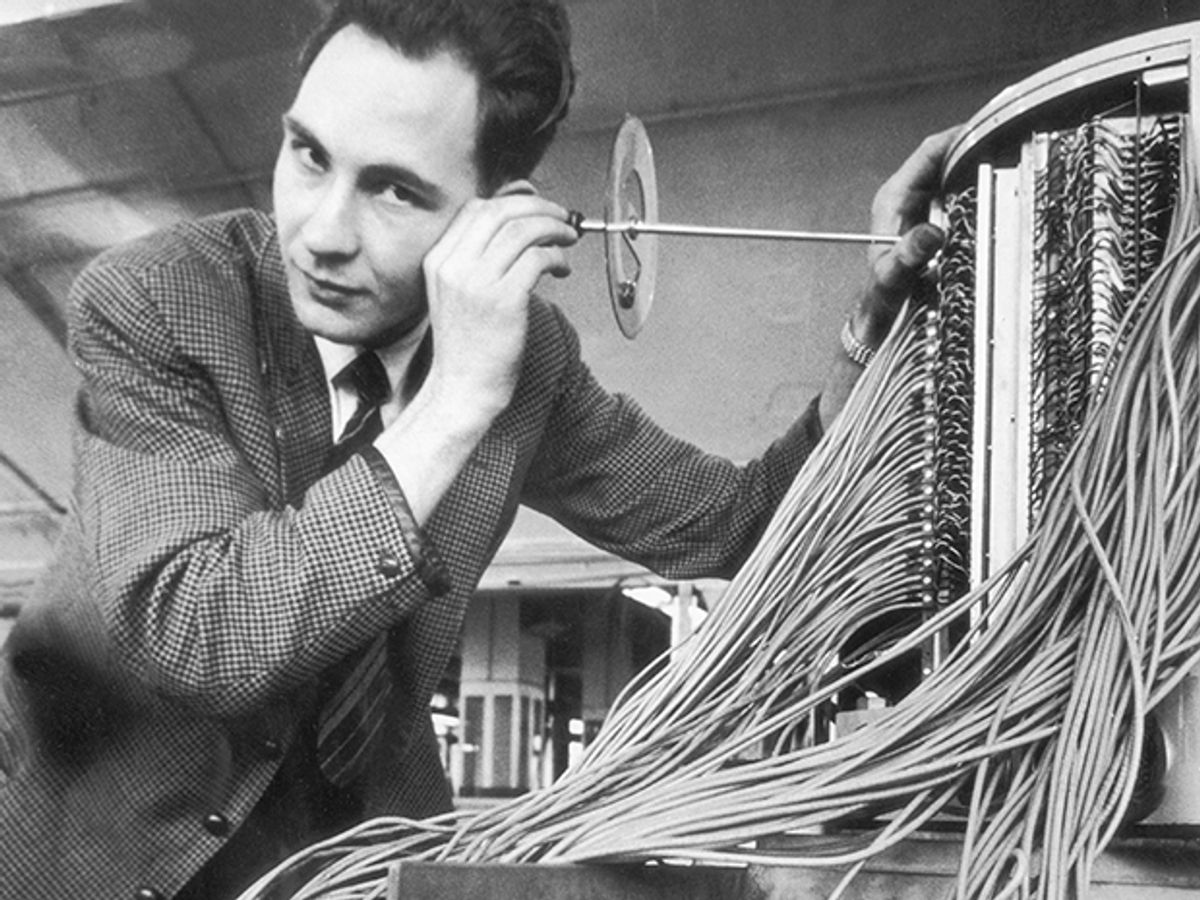

The Ferranti Mark 1’s unique memory system (part of which is shown above) could store just over a kilobyte of data in cathode-ray tubes for high-speed access; a rotating magnetic drum offered 82 kilobytes of permanent storage. The mathematician Mary Lee Berners-Lee recounted the trials of programming a Ferranti Mark 1 in a 2001 oral history: “[W]hat you could do on that machine was make it go through one instruction at a time, and watch actually what was happening on the cathode-ray tubes. But that, of course, took a lot of computer time, and you would have people in the queue waiting to use the computer behind you. There was a big notice over the computer—I think it was [a play on the one] devised by IBM—which said, ‘Think—but not here!’ ” [For more details about the programming, see Brian Napper's account here.]

In 1948, Alan Turing and David Champernowne devised a set of rules for a chess program called Turochamp, which Turing had started to code for the University of Manchester’s Ferranti Mark 1 before his untimely death. In a game against colleague Alick Glennie, Turing worked through the Turochamp algorithm by hand, which took him half an hour per move. The game reportedly lasted several weeks, and Turochamp lost in 29 moves.

As for what the fellow is doing in this photo, or who he is, we don’t know. We invite readers to tell us.

This article appears in the May 2016 print issue as “Listening for Gremlins.”

Part of a continuing series looking at old photographs that embrace the boundless potential of technology, with unintentionally hilarious effect.

Editor’s Note, 30 January 2020:

Simon Lavington, Emeritus Professor at the University of Essex, has provided some insight about what’s probably going on here:

My guess is that he is a Ferranti maintenance engineer adjusting the read/write heads on a Mark I* drum. The head-mountings had a built-in micrometer adjuster, which allowed fine positioning of the head’s surface relative to the surface of the drum. The procedure was to set the drum spinning and then wind in each head in turn until it was heard to be just touching the drum’s surface. Due to minor imperfections in the drum’s mounting and in the thickness of the drum’s nickel plating, the drum was not exactly cylindrical. Therefore the precise distance between each head and its adjacent region of drum surface would vary very very slightly, depending upon the rotational position of the drum. So the engineer gently turned in the micrometer adjuster until a ‘Ping’ was heard as the head just touched the nearest part of the drum’s surface. The micrometer was then backed off a fraction. The result was that this particular head was positioned as close as possible to the drum’s surface.

For more details about the Ferranti computers, check out Simon’s book, Early Computing in Britain: Ferranti Ltd. and Government Funding, 1948–1958 (Springer, 2019).