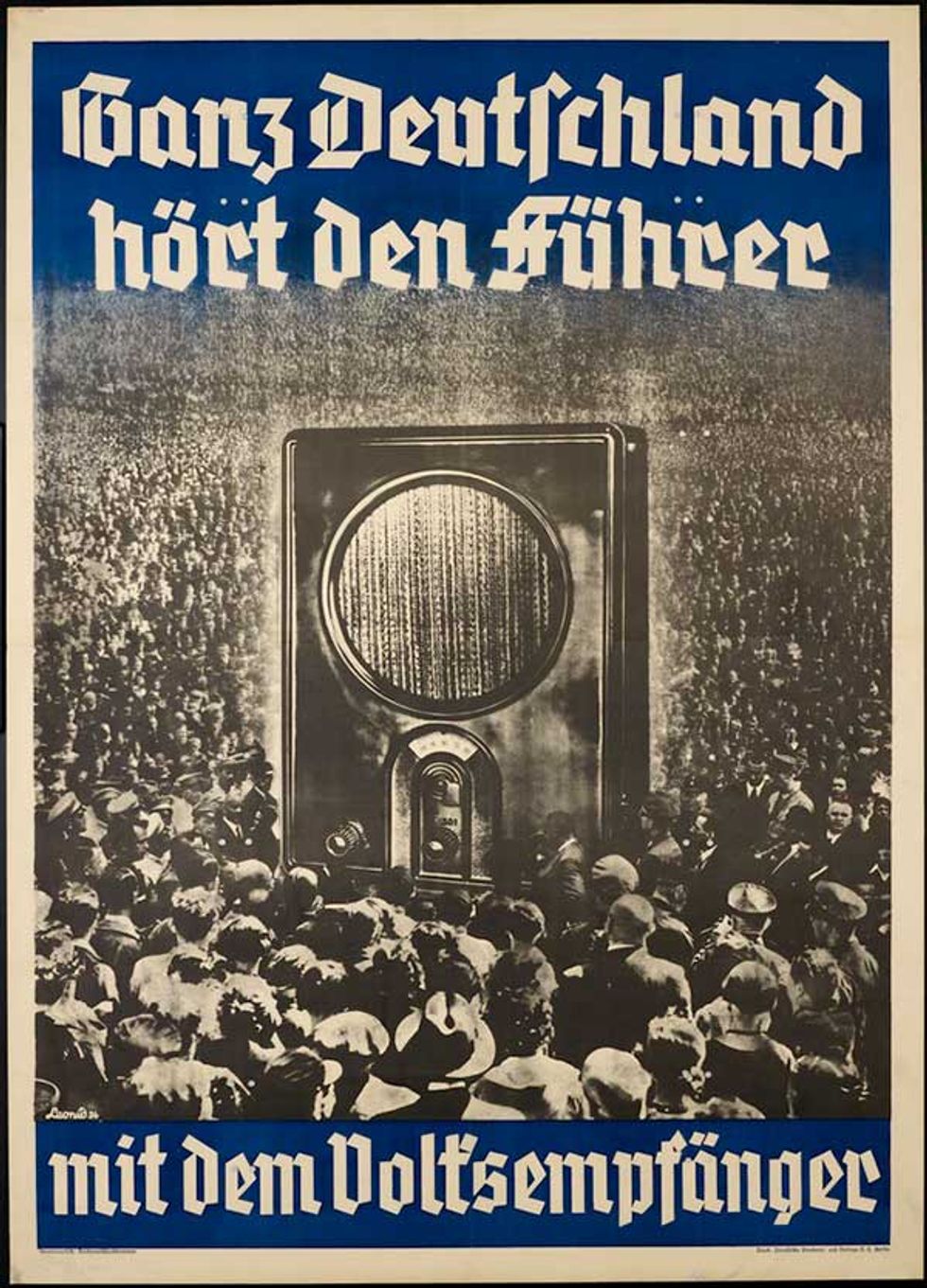

Joseph Goebbels understood the art of persuasion. As propaganda minister for the Nazis, he sought to exploit radio's tremendous potential to broadcast Hitler's messages. But first he needed a way for people to tune in.

Radio helped bring the Nazis to power and keep them there

On 18 August 1933, Goebbels opened the 10th International Radio Show, in Berlin, with a speech declaring “Radio as the Eighth Great Power"—a nod to Napoleon's notion that the press was the seventh great power. Goebbels argued that “the radio will be for the twentieth century what the press was for the nineteenth century." He noted the failure of the Weimar Republic to embrace radio and claimed that the National Socialists would not have been able to take power without it.

“We want a radio that reaches the people, a radio that works for the people, a radio that is an intermediary between the government and the nation, a radio that also reaches across our borders to give the world a picture of our character, our life, and our work," Goebbels proclaimed.

To make that happen, Geobbels had seized control of the Reichs-Rundfunk-Gesellschaft—the Reich Broadcasting Corporation— a national network of regional broadcasting companies. After solidifying control of the broadcast infrastructure, he imposed rules on permissible content. His final task was to make sure everyone had access to an affordable radio receiver. But radios in Germany in the early 1930s were expensive, easily exceeding a month's wages for ordinary workers.

Goebbels approached electrical engineer Otto Griessing to design a radio that was technically simple, easy to mass-produce, and inexpensive. The result was the Volksempfänger (“people's receiver" or “people's radio"), which Goebbels introduced at the Berlin show. At a subsidized 76 Reichsmarks (about US $250), it was about half the price of the cheapest radios then on the market. More than 100,000 units sold during the first two days of the exhibition. The radio could also be purchased on installment. By 1941, nearly two-thirds of German households owned a Volksempfänger, and Goebbels had succeeded in giving Hitler a direct conduit into people's homes via the airwaves.

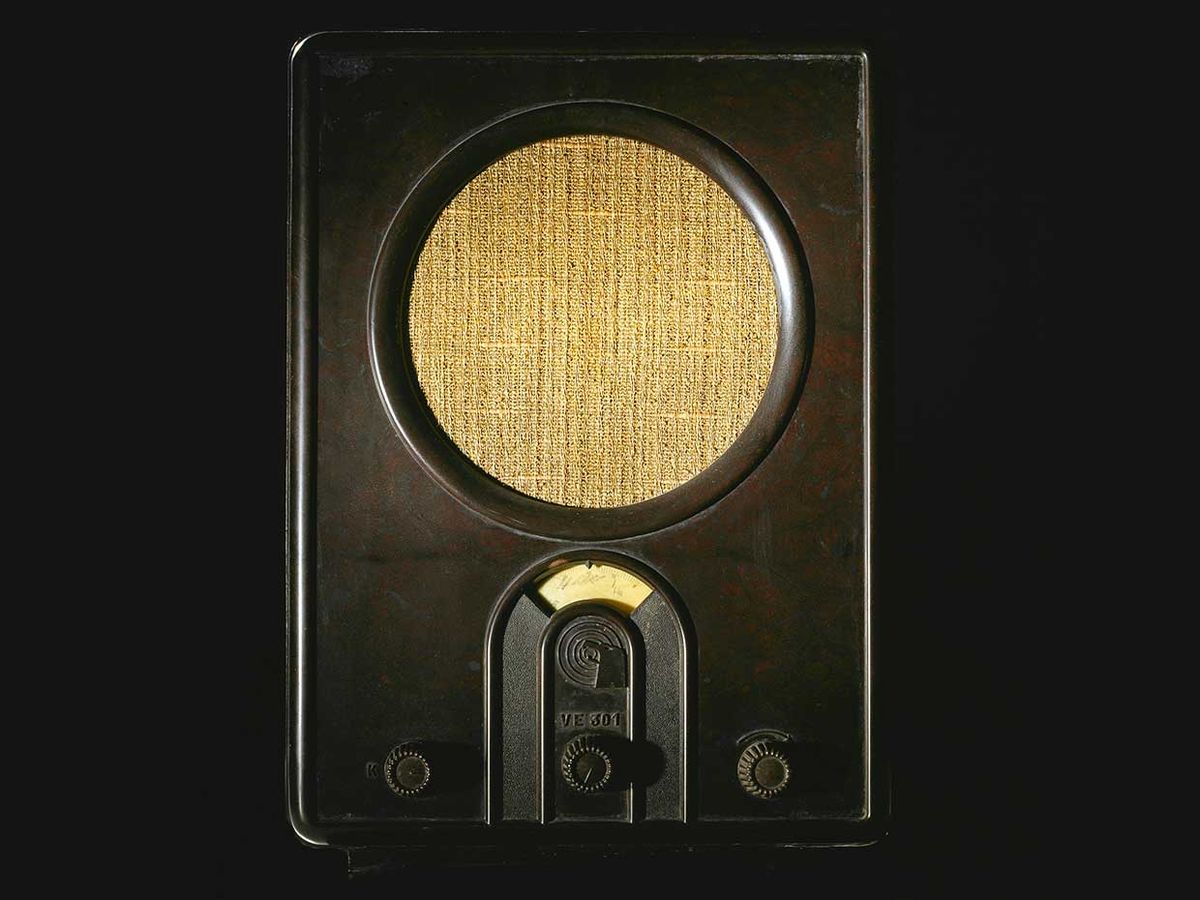

The Volksempfänger was a model of German engineering

The Volksempfänger was designated model VE301, a reference to 30 January, the day in 1933 that Adolf Hitler assumed power. It was a three-tube receiver that operated in long-wave and medium-wave bands—150 to 350 kilohertz and 550 to 1700 kilohertz, respectively—and had a built-in magnetic loudspeaker. The radio came in three versions: The VE301 W ran on alternating current, the VE301 B was battery powered, and the VE301 G operated on direct current. The W and B sold for 76 RM, while the G was priced at 65 RM. All of the models had sockets on the left side for plugging in antennas of different lengths. A later model, the VE301 Dyn, introduced in 1938, featured an electrodynamic loudspeaker.

The Volksempfänger's radio dial was not marked off in frequencies but rather listed the names of cities—Frankfurt and Heidelberg are among the cities on the Deutsches Museum's Volksempfänger [pictured at top]. The two tuning knobs on the front had to be turned in tandem to acquire a new station. An ear-splitting screech could result when the receiver went out of tune. The Volksempfänger did have the sensitivity to pick up foreign broadcasts, but after the start of World War II in 1939, listening to them became punishable by fines, imprisonment, and even death.

Low cost was not the only reason for the Volksempfänger's popularity. The original VE301 had an attractive art deco-inspired design. Industrial designer Walter Maria Kersting fabricated the cabinet out of Bakelite, a plastic that could be easily molded. Bakelite also had insulating properties that made it ideal for the electronics industry, replacing the heavy and more expensive wood cabinetry that was then common. Unfortunately, the later VE301 Dyn lacked some of the radio's original flair. It had a rectangular speaker and tuning window, giving it a much more utilitarian aesthetic.

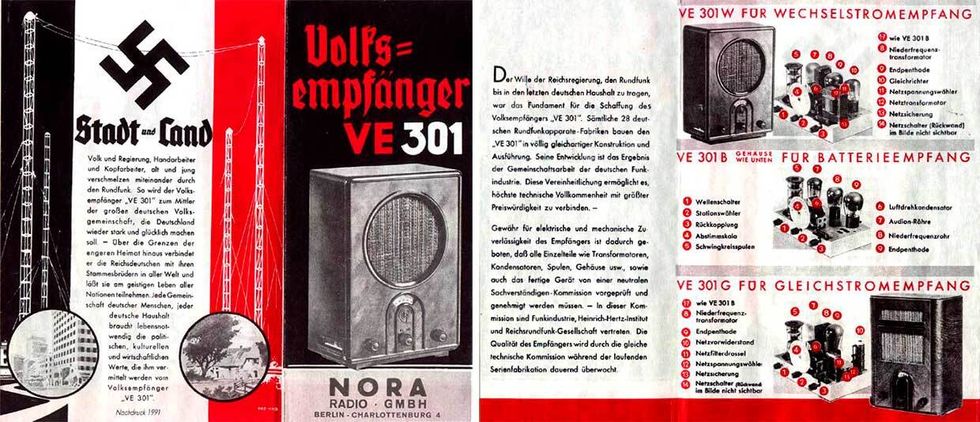

The government pressured 28 German radio manufacturers, including Philips, Siemens, and Telefunken, into producing the VE301. They were required to adhere to strict standards and could not alter the circuitry or housing. The only distinguishing mark they were allowed was a stamp of the company name on the back cover. A committee of experts from the radio industry, the Institute for Oscillation Research (known as the Heinrich Hertz Institute before and after Nazi control), and the Reich Broadcasting Corporation assured quality control and technical compliance. But the Volksempfänger didn't hold a total monopoly. Manufacturers were still allowed to produce other radios and to price them at market rates.

For the German people, the Volksempfänger offered welcome distraction

The original marketing materials for the VE301 made no secret of Goebbels's plan to bring radio to as many Germans as possible. One brochure claimed the radio brought together “city and country, people and government, manual laborers and office workers, old and young" through broadcasting.

Ads positioned the Volksempfänger as the intermediary for the greater German community that would make the country strong and prosperous again by bringing political, cultural, and economic ideas into every household. The national emblem of the eagle near the tuning dial identifies the product as part of state propaganda efforts. Later models also included a swastika.

An even cheaper version of the radio, the Kleinemfänger, came out in 1938 and sold for 35 Reichsmarks. It earned the nickname Goebbels-Shnauze, or “Goebbels' snout," partly because it looked like a big blunt nose, but mostly because it was the mouthpiece for Goebbel. In Jan Eliasberg's 2020 novel Hannah's War (Little, Brown), a fictional account of the life of the Austrian Jewish physicist Lise Meitner, the Goebbels-Shnauze comes up in conversation when a U.S. military investigator is trying to make small talk with Hannah, who is working on the Manhattan Project.

Goebbels knew better than to simply broadcast the Third Reich's agenda nonstop. People welcomed the inexpensive receivers into their homes precisely because they also provided entertainment and distraction. Regular programming included operas, classical concerts, light dance music, games, jokes, and popular arts.

To be sure, programming was highly censored. Forbidden content included “corrupted music," such as American jazz, pop, and swing. The censorship didn't seem to bother listeners. In her 2019 book News from Germany: The Competition to Control World Communications, 1900–1945 (Harvard University Press), historian Heidi Tworek notes that “the Nazis used entertainment programs to lure more people into listening to Hitler's speeches."

That assertion is supported by oral histories conducted by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The Volksempfänger is mentioned repeatedly, unprompted by direct questions. For example, Rolf Kreisch, who joined the Hitler Youth and then the German army, remembered that ordinary people were offered a radio for 35 marks through the Kraft durch Freude, a Nazi organization that gave benefits to party loyalists. In his 1999 oral history, Kreisch recalled that people were enthusiastic about the perks of party membership and listened to the radio, even if they didn't agree with all aspects of the party.

Johann Balogh, an Austrian who was interviewed in 2019, recalled that his village of Althodis received two Volksempfängers, which were placed in public places in the city center. He and his family often went there to hear the broadcasts. Althodis was a mostly Catholic community, with a small Roma population. One night the police removed all of the Roma, Balogh recalled, and nobody put up a fight. Although he did not connect the radio to the disappearance of his neighbors, the incident captures the insidious nature of propaganda—when it works, people accept it without question. Balogh later wrote a book documenting the lives of the Roma in Althodis.

The Kreisch and Balogh oral histories are part of an initiative to record the testimonies of non-Jewish witnesses to the Holocaust. That the interviewees could recall, with fondness, the details of a radio decades later shows how deeply it infiltrated popular culture. People viewed it not as a cold tool of propaganda but as a welcome sign of normalcy and progress—exactly as Goebbels had intended.

Ultimately, according to Tworek, Goebbels's propaganda machine and the Volksempfänger transformed the soundscape of cities across Germany and led to a uniformity of culture. After World War II, scholars of mass communication began to study such uses of radio and other technologies, looking into the connections among politics, media, culture, and authoritarianism.

Is social media the 21st-century equivalent of Goebbels's radio?

If radio was in fact the great power of the 20th century, then social media may be the great power of the 21st. In recent years, many people have compared the Nazis' manipulation of radio to mobilize hate with the use of the Internet and social media to radicalize fringe groups and disseminate false information.

Since 2008, social media expert Andre Oboler has been documenting and analyzing online hate and advising groups on how to combat it. A computer scientist by training, he founded the Online Hate Prevention Institute in 2012 to investigate cyber-racism, violent extremism, misogyny, trolling, and griefing (sabotage within online games and other virtual platforms). In a November 2020 address to the United Nations' Forum on Minority Issues, he noted that hate is often based on ignorance, fed by fake news, misinformation, and disinformation—tactics straight out of Goebbels's playbook.

Goebbels ended his speech at the 1933 Berlin radio show with a high-minded wish: to unite science, industry, and intellectual leadership with a common goal of a “glorious German future." His success in this effort helped trigger a world war while concealing an architected program of genocide, mass murder, and oppression.

Thinking about the uses of the Volksempfänger and of social media, I'm reminded of the late historian of technology Melvin Kranzberg and his six laws of technology, the first of which states: “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral." The elegant and inexpensive Volksempfänger perfectly embodied that law: It gave ordinary Germans access to entertainment and culture, but it also became an instrument of hate. The same can be said of social media, as we now know. It's only prudent to approach even the most neutral-seeming technology with a critical eye.

Part of a continuing series looking at photographs of historical artifacts that embrace the boundless potential of technology.

An abridged version of this article appears in the April 2021 print issue as “The Nazi Radio."

Allison Marsh is a professor in Women and Gender Studies at the University of South Carolina and codirector of the university’s Ann Johnson Institute for Science, Technology & Society. She combines her interests in engineering, history, and museum objects to write the Past Forward column, which tells the story of technology through historical artifacts. Marsh is currently working on a book on the history of women in electrical engineering.