For more than a century, fashion-conscious consumers have relied on an electric hot comb to style their hair. Also known as a singeing comb, this versatile tool straightens and smooths coarse hair and adds a wave or curl to fine hair.

A hot comb looks like a standard comb, but it’s usually heavier, and its metal teeth are spaced further apart. To use it, you section off a piece of hair, apply an oil or tonic such as petroleum jelly, and then run the hot comb down the length of the hair at a steady pace to avoid singeing the hair. A non-heat-conducting handle allows the user to manipulate the comb without burning her hands. Care is also needed to avoid burning the scalp or neck. The pursuit of beauty can be painful.

The hot comb—much like the clothes iron and some other heated consumer gadgets—predates electrification. The original ones were made from ceramic or metal and were heated in a water bath or over a gas burner. Although the device could be considered an anonymous technology—that is, a tool that has evolved without clearly identified inventors or inventors whom history has forgotten–there are a few people credited with popularizing the hot comb.

First is the Frenchman François Marcel Grateau, who invented a heated curling iron around 1872. His iron looked like a pair of tongs and was used to create the marcel wave, a hairstyle of cascading waves that was popular across Europe and North America for decades. Grateau later immigrated to the United States, changed his name to François Marcel Woelfflé, and in 1905 was granted a U.S. patent for his curling iron. In 1918 he patented an electric version. By electrically heating the iron to a controlled temperature, he claimed, the device could produce longer lasting waves without injuring or burning the hair.

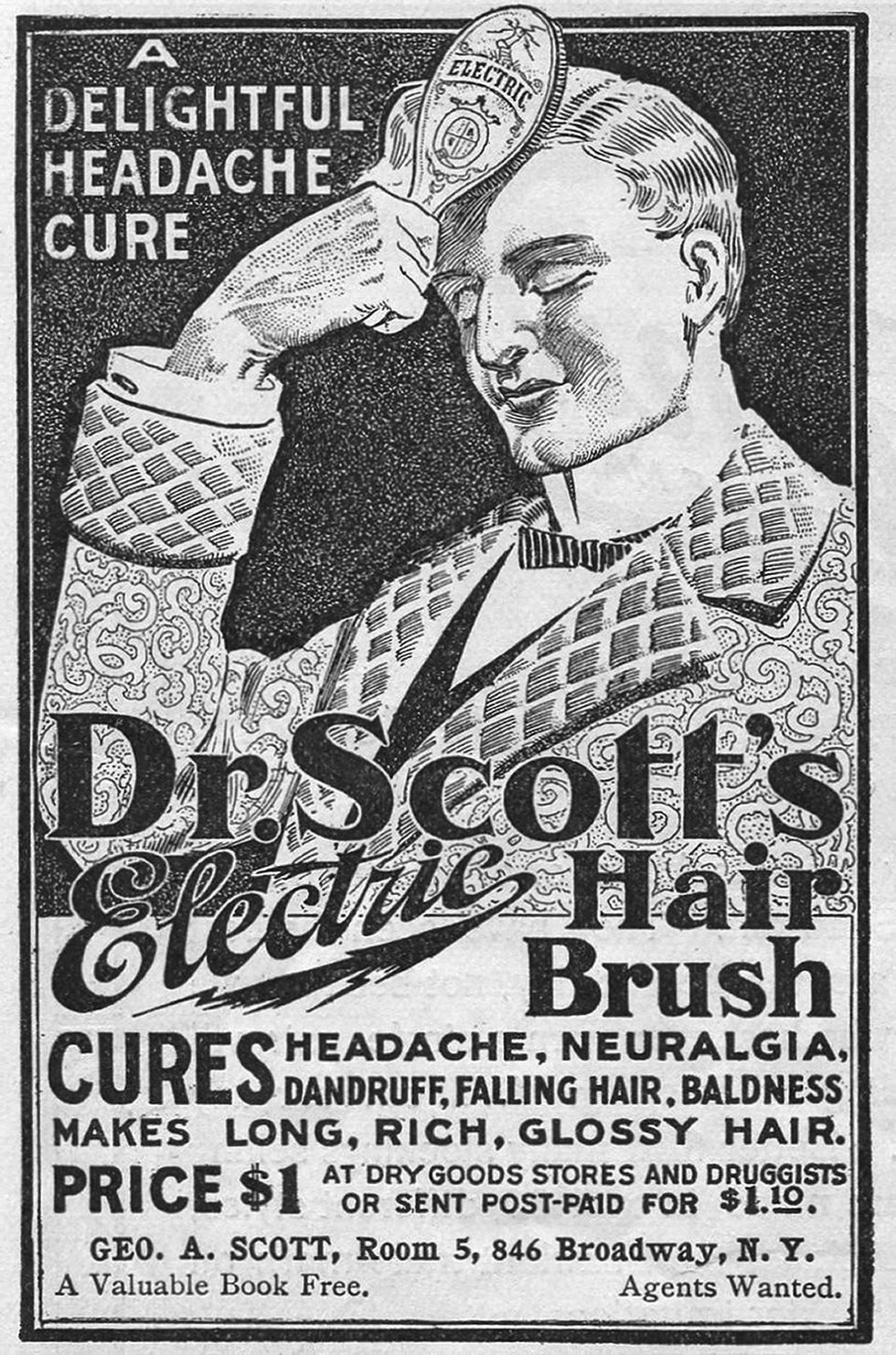

During the 1880s, a U.S. inventor and entrepreneur named George Augustus Scott sold an electric comb as part of his comprehensive line of Dr. Scott beauty products, which also included crimpers, curlers, and corsets. According to advertisements, Dr. Scott’s Electric Curler could curl a man’s beard or mustache into any style desired in one to two minutes. Ladies could use the same device to do their hair in the fashionable “loose and fluffy” style of actress Lillie Langtry or opera singer Adelina Patti.

Scott claimed his products had curative properties beyond their purported aesthetic value. His electric hair brush, for instance, was the solution to dandruff, balding, headaches, and neuralgia. At the time, such health-inducing electrotherapy products were all the rage.

Despite the name, however, Scott’s devices weren’t actually electric: They did not plug into an electric power source, nor were they battery operated. They did have embedded magnets, and so he was using the term “electric” to mean magnetic. But small magnets would not have produced the amazing effects that Scott touted. Sometimes an electric comb is just a comb.

Like most U.S. beauty products of the day, Scott’s and Grateau’s devices were designed for whites. Relatively few hair-care products catered to African Americans. At the turn of the 20th century, three women sought to change that, and they built up hugely successful businesses in the process.

The first was Annie Turnbo Malone. Starting in 1900, Malone manufactured her hair-care treatments under the brand name Poro and sold them door to door in St. Louis through a network of saleswomen. In 1917, she set up a training institute, known as Poro College, to educate women about black cosmetology. She later expanded to Chicago and a number of other cities and countries.

Sarah Breedlove McWilliams Davis was also living in St. Louis at the turn of the 20th century. She suffered from both dandruff and balding, which she blamed on the harsh chemicals used in shampoos and hair styling products. In search of a remedy, she learned about Malone’s products and then became a sales agent for Poro.

In 1905 Davis moved to Denver. While she continued to sell the Poro line, she also began developing her own formulas. In 1906 Davis married Charles Joseph Walker and set up her own business under the name Madam C.J. Walker. Two years later, she relocated to Pittsburgh, where she set up a beauty school called Lelia College. When Malone heard about Davis’s activities, she responded at first by writing cautionary letters and running ads in newspapers. She also pursued copyrights for her formulas. Eventually she started the competing Poro College.

The third woman entrepreneur to champion African American hair care was Sara Spencer Washington, who opened a small beauty shop and began selling her line of products door to door in Atlantic City, N.J., in 1913. Sometime around 1920, she founded the Apex News and Hair Company, and like Malone and Davis, she set up training schools. By 1938, there were 10 Apex Beauty Culture Schools across the United States as well as one in South Africa.

These three businesswomen, each with her own line of products and her own techniques, set the stage for training generations of African American beauticians. The Madam C.J. Walker method used a hot comb, Poro preferred a hair-puller iron, and Apex a curling iron. So in demand were their offerings that all three women became millionaires, at a time when such status was rare for women and for African Americans. As Washington was fond of saying, “As long as there are women in the world, there will be beauty establishments.”

Just as the history of the hot comb has been anonymized, so has much of the history of the users of hot combs. The activities of countless hairdressers, beauticians, and ordinary women rarely get recorded unless the objects they used are donated to a museum. Such is the case with the hot comb shown at top: It belonged to Edna Stevens McIntyre, a longtime resident of Washington, D.C.; it was made by the Solar Electric Manufacturing Company of San Francisco; and it was given to the National Museum of African American History and Culture by McIntyre’s niece. Unfortunately, I could find very little public information about McIntyre, who died in 2017 at the age of 99.

Small, local museums sometimes do a better job of documenting everyday life than do larger institutions. As part of my research for this article, I recently visited the King-Tisdell Cottage in Savannah, Ga. This historic house museum traces several generations of a successful entrepreneurial African American family.

One prominent member was Alma Porter Tisdell, who began working as a beautician in the 1940s after earning a degree from Georgia State Industrial College for Colored Youth (now Savannah State University) and training at the Apex Beauty School in Philadelphia. On display at the King-Tisdell Cottage are Alma’s marcel tongs and her handwritten notes on how to use them, as well as a special gas burner for heating hot combs and curling irons and a selection of hair clippers. She was the proprietor of Alma’s Beauty Shop in Savannah until the 1980s.

The museum’s fascinating display of everyday objects tell a rich story, and one that’s omitted from most histories of early consumer electronics, which tend to focus on radios and telephones or household appliances like washing machines and refrigerators. Such histories miss the multimillion-dollar industry that provided autonomy and financial independence for hundreds of thousands of African American women. At a time when most could find work only as servants, cleaners, or washerwomen, employment as a beautician commanded respect within their communities. The anonymous technologies that helped them get there should also be remembered.

An abridged version of this article appears in the September 2019 print issue as “Cruel Beauty.”

Part of a continuing serieslooking at photographs of historical artifacts that embrace the boundless potential of technology.

About the Author

Allison Marsh is an associate professor of history at the University of South Carolina and codirector of the university’s Ann Johnson Institute for Science, Technology & Society.