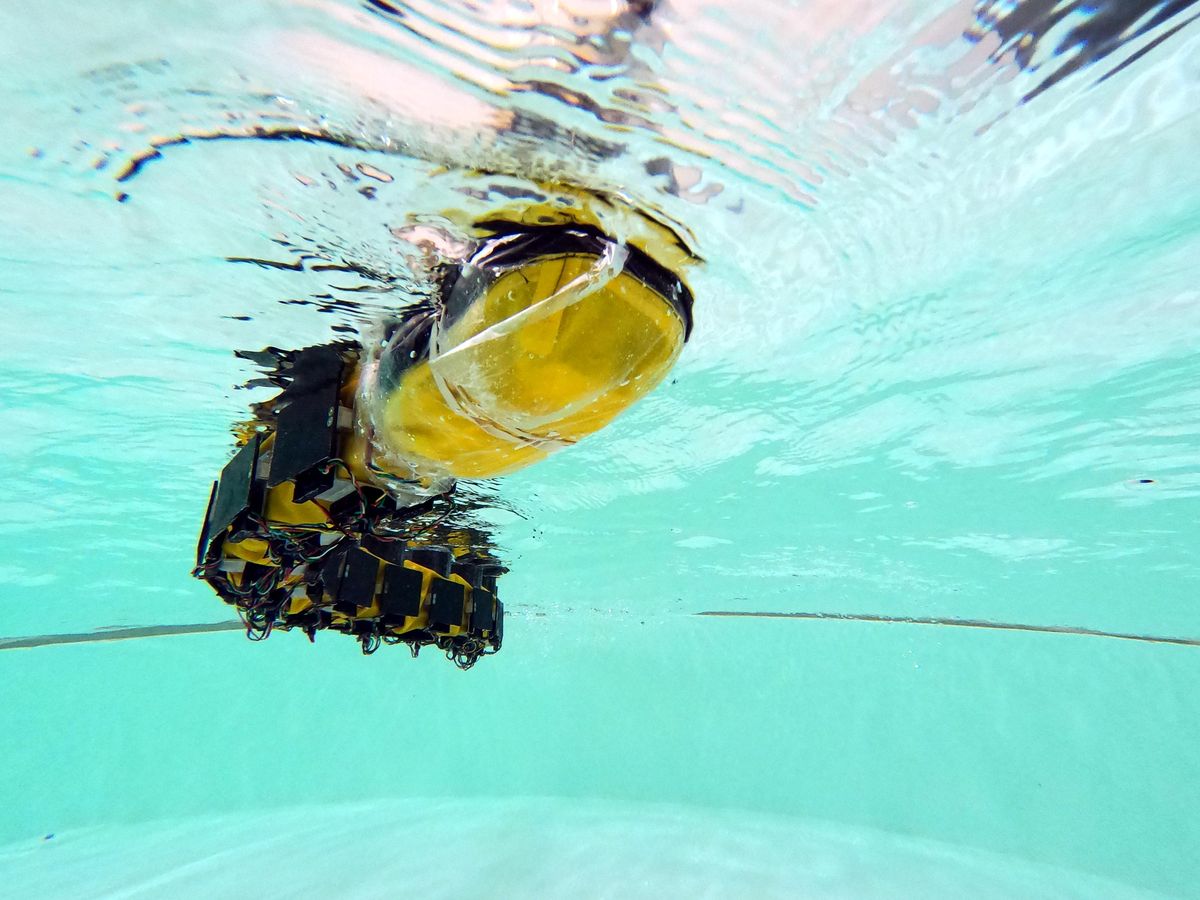

Lots of robots use bioinspiration in their design. Humanoids, quadrupeds, snake robots—if an animal has figured out a clever way of doing something, odds are there's a robot that's tried to duplicate it. But animals are often just a little too clever for the robots that we build that try to mimic them, which is why researchers at Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne in Switzerland (EPFL) are using robots to learn about how animals themselves do what they do. In a paper published today in Science Robotics, roboticists from EPFL's Biorobotics Laboratory introduce a robotic eel that leverages sensory feedback from the water it swims through to coordinate its motion without the need for central control, suggesting a path towards simpler, more robust mobile robots.

The robotic eel—called AgnathaX—is a descendant of AmphiBot, which has been swimming around at EPFL for something like two decades. AmphiBot's elegant motion in the water has come from the equivalent what are called central pattern generators (CPGs), which are sequences of neural circuits (the biological kind) that generate the sort of rhythms that you see in eel-like animals that rely on oscillations to move. It's possible to replicate these biological circuits using newfangled electronic circuits and software, leading to the same kind of smooth (albeit robotic) motion in AmphiBot.

Biological researchers had pretty much decided that CPGs explained the extent of wiggly animal motion, until it was discovered you can chop an eel's spinal cord in half, and it'll somehow maintain its coordinated undulatory swimming performance. Which is kinda nuts, right? Obviously, something else must be going on, but trying to futz with eels to figure out exactly what it was isn't, I would guess, pleasant for either researchers or their test subjects, which is where the robots come in. We can't make robotic eels that are exactly like the real thing, but we can duplicate some of their sensing and control systems well enough to understand how they do what they do.

AgnathaX exhibits the same smooth motions as the original version of AmphiBot, but it does so without having to rely on centralized programming that would be the equivalent of a biological CPG. Instead, it uses skin sensors that can detect pressure changes in the water around it, a feature also found on actual eels. By hooking these pressure sensors up to AgnathaX's motorized segments, the robot can generate swimming motions even if its segments aren't connected with each other—without a centralized nervous system, in other words. This spontaneous syncing up of disconnected moving elements is called entrainment, and the best demo of it that I've seen is this one, using metronomes:

UCLA Physics

The reason why this isn't just neat but also useful is that it provides a secondary method of control for robots. If the centralized control system of your swimming robot gets busted, you can rely on this water pressure-mediated local control to generate a swimming motion. And there are applications for modular robots as well, since you can potentially create a swimming robot out of a bunch of different physically connected modules that don't even have to talk to each other.

For more details, we spoke with Robin Thandiackal and Kamilo Melo at EPFL, first authors on the Science Robotics paper.

IEEE Spectrum: Why do you need a robot to do this kind of research?

Thandiackal and Melo: From a more general perspective, with this kind of research we learn and understand how a system works by building it. This then allows us to modify and investigate the different components and understand their contribution to the system as a whole.

In a more specific context, it is difficult to separate the different components of the nervous system with respect to locomotion within a live animal. The central components are especially difficult to remove, and this is where a robot or also a simulated model becomes useful. We used both in our study. The robot has the unique advantage of using it within the real physics of the water, whereas these dynamics are approximated in simulation. However, we are confident in our simulations too because we validated them against the robot.

How is the robot model likely to be different from real animals? What can't you figure out using the robot, and how much could the robot be upgraded to fill that gap?

Thandiackal and Melo: The robot is by no means an exact copy of a real animal, only a first approximation. Instead, from observing and previous knowledge of real animals, we were able to create a mathematical representation of the neuromechanical control in real animals, and we implemented this mathematical representation of locomotion control on the robot to create a model. As the robot interacts with the real physics of undulatory swimming, we put a great effort in informing our design with the morphological and physiological characteristics of the real animal. This for example accounts for the scaling, the morphology and aspect ratio of the robot with respect to undulatory animals, and the muscle model that we used to approximately represent the viscoelastic characteristics of real muscles with a rotational joint.

Upgrading the robot is not going to be making it more "biological." Again, the robot is part of the model, not a copy of the real biology. For the sake of this project, the robot was sufficient, and only a few things were missing in our design. You can even add other types of sensors and use the same robot base. However, if we would like to improve our robot for the future, it would be interesting to collect other fluid information like the surrounding fluid speed simultaneously with the force sensing, or to measure hydrodynamic pressure directly. Finally, we aim to test our model of undulatory swimming using a robot with three-dimensional capabilities, something which we are currently working on.

Upgrading the robot is not going to be making it more “biological." The robot is part of the model, not a copy of the real biology.

What aspects of the function of a nervous system to generate undulatory motion in water aren't redundant with the force feedback from motion that you describe?

Thandiackal and Melo: Apart from the generation of oscillations and intersegmental coupling, which we found can be redundantly generated by the force feedback, the central nervous system still provides unique higher level commands like steering to regulate swimming direction. These commands typically originate in the brain (supraspinal) and are at the same time influenced by sensory signals. In many fish the lateral line organ, which directly connects to the brain, helps to inform the brain, e.g., to maintain position (rheotaxis) under variable flow conditions.

How can this work lead to robots that are more resilient?

Thandiackal and Melo: Robots that have our complete control architecture, with both peripheral and central components, are remarkably fault-tolerant and robust against damage in their sensors, communication buses, and control circuits. In principle, the robot should have the same fault-tolerance as demonstrated in simulation, with the ability to swim despite missing sensors, broken communication bus, or broken local microcontroller. Our control architecture offers very graceful degradation of swimming ability (as opposed to catastrophic failure).

Why is this discovery potentially important for modular robots?

Thandiackal and Melo: We showed that undulatory swimming can emerge in a self-organized manner by incorporating local force feedback without explicit communication between modules. In principle, we could create swimming robots of different sizes by simply attaching independent modules in a chain (e.g., without a communication bus between them). This can be useful for the design of modular swimming units with a high degree of reconfigurability and robustness, e.g. for search and rescue missions or environmental monitoring. Furthermore, the custom-designed sensing units provide a new way of accurate force sensing in water along the entirety of the body. We therefore hope that such units can help swimming robots to navigate through flow perturbations and enable advanced maneuvers in unsteady flows.

Evan Ackerman is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum. Since 2007, he has written over 6,000 articles on robotics and technology. He has a degree in Martian geology and is excellent at playing bagpipes.