In March, because of the coronavirus, self-driving car companies, including Argo, Aurora, Cruise, Pony, and Waymo, suspended vehicle testing and operations that involved a human driver. Around the same time, Waymo and Ford released open data sets of information collected during autonomous-vehicle tests and challenged developers to use them to come up with faster and smarter self-driving algorithms.

These developments suggest the self-driving car industry still hopes to make meaningful progress on autonomous vehicles (AVs) this year. But the industry is undoubtedly slowed by the pandemic and facing a set of very hard problems that have gotten no easier to solve in the interim.

Five years ago, several companies including Nissan and Toyota promised self-driving cars in 2020. Lauren Isaac, the Denver-based director of business initiatives at the French self-driving vehicle company EasyMile, says AV hype was “at its peak” back then—and those predictions turned out to be far too rosy.

Now, Isaac says, many companies have turned their immediate attention away from developing fully autonomous Level 5 vehicles, which can operate in any conditions. Instead, the companies are focused on Level 4 automation, which refers to fully automated vehicles that operate within very specific geographical areas or weather conditions. “Today, pretty much all the technology developers are realizing that this is going to be a much more incremental process,” she says.

For example, EasyMile’s self-driving shuttles operate in airports, college campuses, and business parks. Isaac says the company’s shuttles are all Level 4. Unlike Level 3 autonomy (which relies on a driver behind the wheel as its backup), the backup driver in a Level 4 vehicle is the vehicle itself.

“We have levels of redundancy for this technology,” she says. “So with our driverless shuttles, we have multiple levels of braking systems, multiple levels of lidars. We have coverage for all systems looking at it from a lot of different angles.”

Another challenge: There’s no consensus on the fundamental question of how an AV looks at the world. Elon Musk has famously said that any AV manufacturer that uses lidar is “doomed.” A 2019 Cornell research paper seemed to bolster the Tesla CEO’s controversial claim by developing algorithms that can derive from stereo cameras 3D depth-perception capabilities that rival those of lidar.

However, open data sets have called lidar doomsayers into doubt, says Sam Abuelsamid, a Detroit-based principal analyst in mobility research at the industry consulting firm Navigant Research.

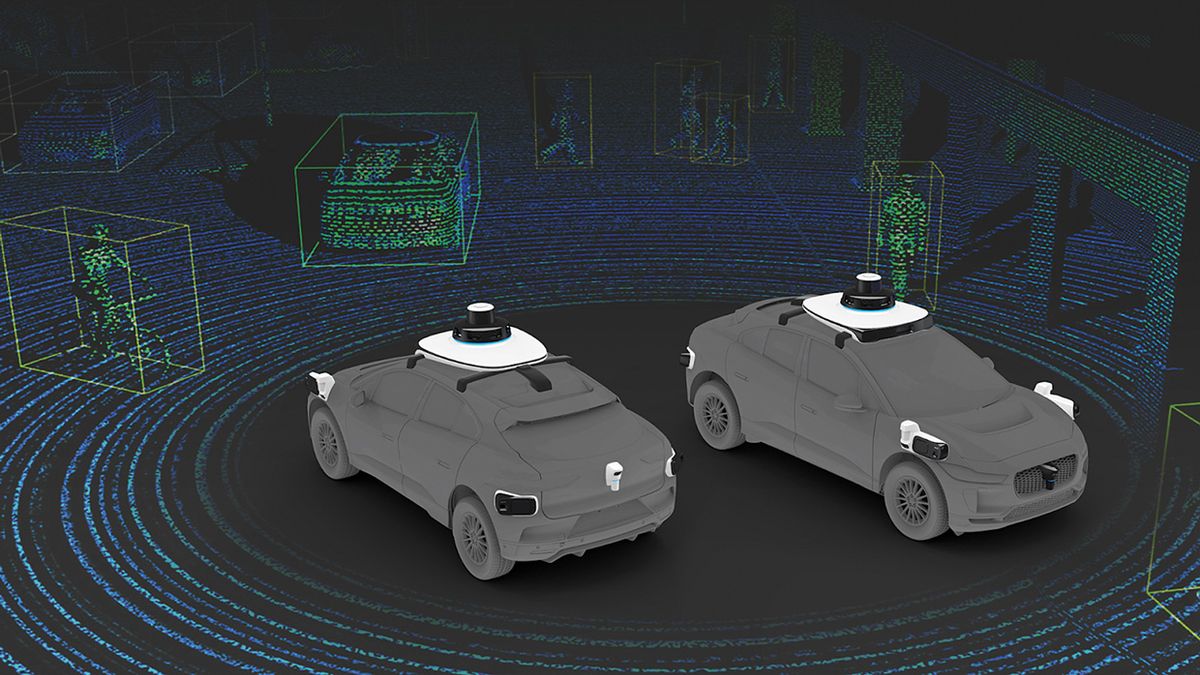

Abuelsamid highlighted a 2019 open data set from the AV company Aptiv, which the AI company Scale then analyzed using two independent sources: The first considered camera data only, while the second incorporated camera plus lidar data. The Scale team found camera-only (2D) data sometimes drew inaccurate “bounding boxes” around vehicles and made poorer predictions about where those vehicles would be going in the immediate future—one of the most important functions of any self-driving system.

“While 2D annotations may look superficially accurate, they often have deeper inaccuracies hiding beneath the surface,” software engineer Nathan Hayflick of Scale wrote in a company blog about the team’s Aptiv data set research. “Inaccurate data will harm the confidence of [machine learning] models whose outputs cascade down into the vehicle’s prediction and planning software.”

Abuelsamid says Scale’s analysis of Aptiv’s data brought home the importance of building AVs with redundant and complementary sensors—and shows why Musk’s dismissal of lidar may be too glib. “The [lidar] point cloud gives you precise distance to each point on that vehicle,” he says. “So you can now much more accurately calculate the trajectory of that vehicle. You have to have that to do proper prediction.”

So how soon might the industry deliver self-driving cars to the masses? Emmanouil Chaniotakis is a lecturer in transport modeling and machine learning at University College London. Earlier this year, he and two researchers at the Technical University of Munich published a comprehensive review of all the studies they could find on the future of shared autonomous vehicles (SAVs).

They found the predictions—for robo-taxis, AV ride-hailing services, and other autonomous car-sharing possibilities—to be all over the map. One forecast had shared autonomous vehicles driving just 20 percent of all miles driven in 2040, while another model forecast them handling 70 percent of all miles driven by 2035.

So autonomous vehicles (shared or not), by some measures at least, could still be many years out. And it’s worth remembering that previous predictions proved far too optimistic.

This article appears in the May 2020 print issue as “The Road Ahead for Self-Driving Cars.”

Margo Anderson is the news manager at IEEE Spectrum. She has a bachelor’s degree in physics and a master’s degree in astrophysics.