For years, brain researchers have experimented with electrical stimulation as a way to improve memory, but with mixed results. The problem with these approaches may have been a matter of timing, according to a report published today in the journal Current Biology. Electrical stimulation should be delivered to the brain precisely when memory is predicted to fail—and not when a memory network is operating efficiently, say the authors of the report.

The proof-of-concept study offers the first clear indication for when to stimulate the brain in a way that affects memory. The study also marks the first major milestone of the U.S. military’s $77 million program to develop an implantable device that improves memory for people with traumatic brain injury (TBI).

DARPA, the research arm of the U.S. Department of Defense, in 2014 began doling out research awards for the program, dubbed Restoring Active Memory, or RAM. Today’s report by a research team led by Michael Kahana, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Computational Memory Lab, resulted from part of the lab’s $22.7 million RAM award.

Kahana’s findings make sense: Don’t interrupt the brain with electrical pulses when it’s in the middle of a thought.

“The notion that you’re going to take a system that’s working efficiently and somehow make it work better—it might be possible, but the technical requirements of doing so are beyond our capabilities currently,” says Kahana. “You’d have to understand the human brain extremely well,” he says, and we just aren’t there yet. So stimulation is more likely to be helpful when the brain is forgetting, he says.

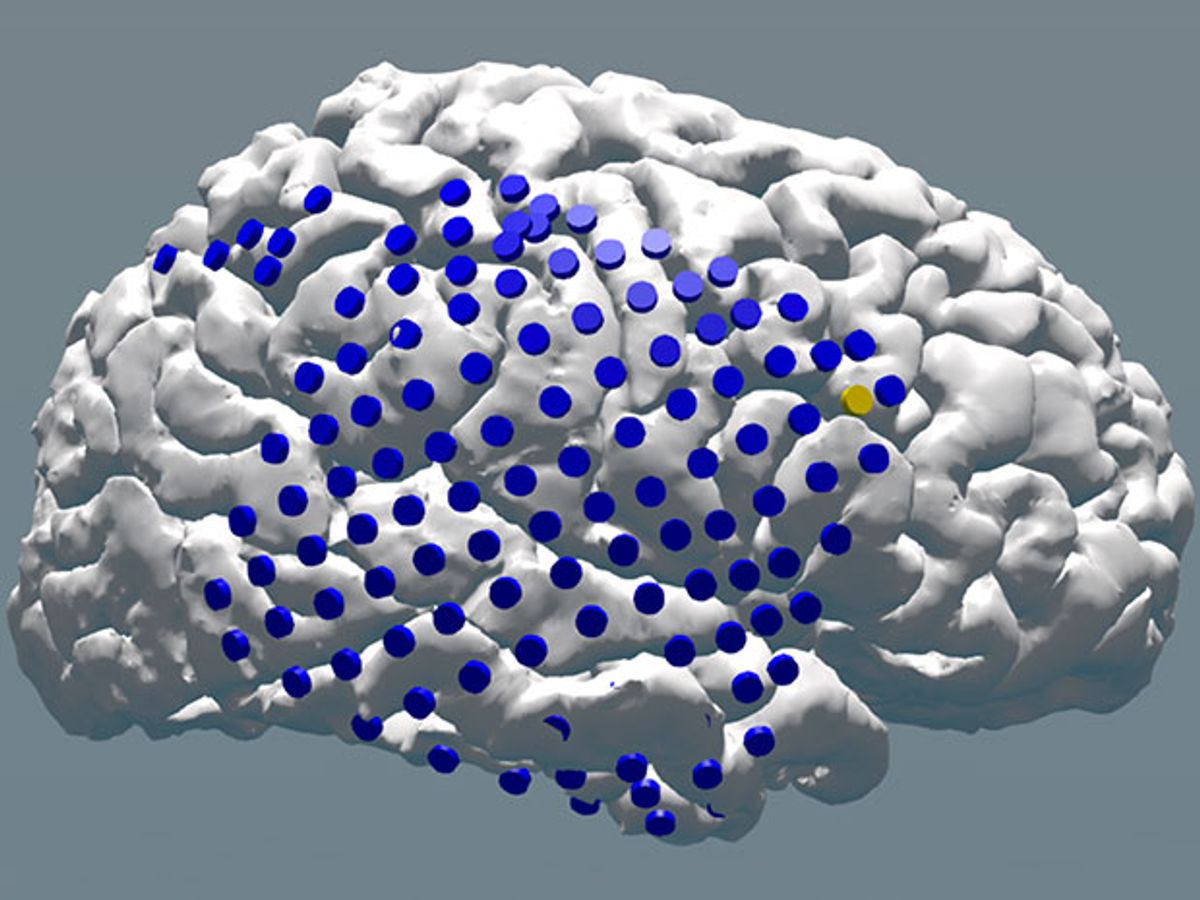

Key to the Penn team’s experiment was being able to read and record brain activity captured through electrodes implanted in the brain, and then analyze that activity with computational models. In the study, 102 people each had about 100 electrode contacts implanted in their brains in various regions. As the subjects viewed lists of words and later tried to remember them, the electrodes recorded their brains’ electrical activity—a process called intracranial electroencephalography, or iEEG.

The researchers then used the EEG readout to train their computational model, a type of machine learning classification algorithm. Based on the patterns of neural activity, the algorithm learned to differentiate when a person is in the process of storing the words to be remembered later versus when the words went in one ear and out the other, so to speak.

In neuroscientist parlance, a brain that is storing information for later use is in a ‘high encoding state,’ which is marked by an increase in fast brain wave activity. The opposite of that—an increase in slow brain wave activity—marks a state of forgetting, or ‘low encoding state.’ The computational model could predict whether a person was going to remember or forget the words on the list based on their encoding state during the task.

Armed with that predictive power, the researchers experimented with delivering electrical pulses to a subset of the study participants. They found that if they delivered the stimulation right after detecting a low encoding state, recall performance improved—like a zap to the brain to tell it to pay attention. If they delivered stimulation right after detecting a high encoding state, recall decreased—like an interruption.

Now that the researchers know when to stimulate, the next step is to determine where to stimulate—which regions of the brain are associated with memory and will respond to electrical pulses.

They must also determine how to stimulate. The aim is to record and then mimic the natural electrical patterns associated with memory in the human brain. It’s like decoding an extremely complex version of Morse code, and then trying to replicate it artificially. That means experimenting with different pulses, waveforms, intensities and frequencies of stimulation. And those parameters will likely differ from one human brain to the next.

The other recipient of DARPA’s RAM funding—a group led by Samuel Deadwyler and Robert Hampson at Wake Forest—is also tackling that question, and is starting to see positive preliminary findings, Justin Sanchez, director of DARPA's Biological Technologies Office, says. The Wake Forest team has not yet reported results.

One reason we don’t know more about brain stimulation is that it has been hard to justify the invasive operations required for such studies. It’s brain surgery, after all, and like any surgery, it carries risk of bleeding, infection and tissue damage.

In the Penn study, the 102 participants were all epilepsy patients who already had electrodes implanted in their brains for clinical treatment of epilepsy. Doctors used the electrodes to find the focal point of seizures in the brain. The Penn group piggy-backed on that treatment by using the same implanted hardware for their study of memory.

The electrodes were placed on the surface of the brain as well as deeper brain structures such as the hippocampus, and kept there for up to three weeks. By contrast, electrodes implanted for deep brain stimulation studies for Parkinson’s disease and depression are typically implanted in areas of the brain that control movement. Only a handful of groups have been able to conduct such studies.

More common are non-invasive brain stimulation techniques, which often involve placing electrodes on the scalp. Academic groups, start-ups, Olympic athletes, and even home tinkerers have explored the approach, called transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Scientists debate, and sometimes doubt, its effectiveness. Perhaps developers of those techniques could learn from Penn’s study: It’s a matter of timing. Wait for the right moment.

Updated 20 April 2017

Emily Waltz is a features editor at Spectrum covering power and energy. Prior to joining the staff in January 2024, Emily spent 18 years as a freelance journalist covering biotechnology, primarily for the Nature research journals and Spectrum. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Discover, Outside, and the New York Times. Emily has a master's degree from Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and an undergraduate degree from Vanderbilt University. With every word she writes, Emily strives to say something true and useful. She posts on Twitter/X @EmWaltz and her portfolio can be found on her website.