The University of Louisville’s breathless excitement over its spinal stimulation research had a gut check this year after an audit uncovered numerous instances where its record keeping did not comply with federal standards.

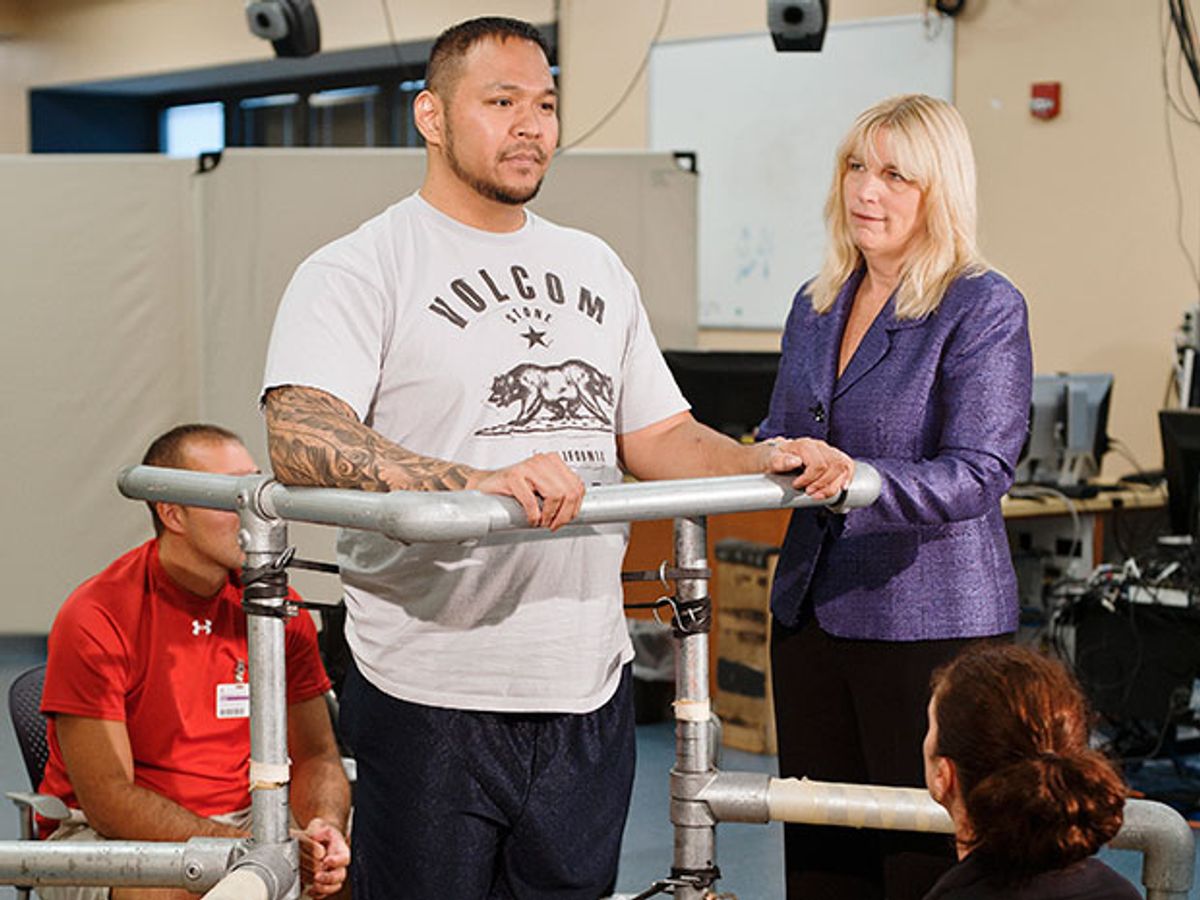

The university’s renowned neuroscientist, Susan Harkema, drew international attention and millions in grant money after she and her colleagues in 2011 revealed that they had enabled a man paralyzed from the chest down to voluntarily move his legs and stand on his own for minutes at a time by electrically stimulating his spinal cord. She repeated the success in three more people with spinal cord injuries. The experiments gave hope to paralyzed people everywhere. [See “An Electrifying Awakening,” IEEE Spectrum, November 2013.]

That hope is still there, but sloppy documentation in four of her studies—three of which involved electrical stimulation—have cast a shadow over the excitement. The group had such poor digital organization of patient records that when the university’s biomedical institutional review board (IRB) audited the studies in 2015, it had trouble evaluating whether Harkema’s group had followed the standard procedures that are essential in rigorous clinical experiments.

Records of patients’ health complications, medication adherence, lab results, follow-up assessments, and eligibility for the studies were scattered in different databases. Changes to study protocols had been made without prior approval of the IRB. It was “nearly impossible to see which [study] protocol procedures have been completed,” wrote the university’s IRB in its audit of a spinal epidural stimulation study called EPI ORIGINAL.

“We modified our standard operating procedures in response to every request and they are now implemented for all of our (group’s) ongoing studies”

The infractions ranged from “educational”—meaning the study investigators needed to be educated on how to comply—to “serious non-compliance” with federal standards.

Patients’ safety was not compromised during the studies and no one was injured during the stimulation studies, the audit said. The IRB recommended that Harkema’s research continue.

Harkema had voluntarily placed all four studies on hold when the IRB began its investigation. The three stimulation studies—two spinal stimulation and one peripheral nerve stimulation—will be completed with a green light from the IRB.

The stimulation studies are funded largely by private groups, including the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation and the Helmsley Charitable Trust. Following the IRB audit, one private funder did its own investigation of the stimulation studies. None have withdrawn their financial support for the projects, Harkema says.

The IRB’s report did, in part, lead one of Harkema’s funders to pull its support of the fourth study, which did not involve electrical stimulation. That project aimed to study the health effects of taking the muscle relaxer Baclofen while undergoing a type of physical therapy called locomotor training in people with spinal cord injury. In March, the U.S. National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR), which had been funding the study as part of a larger spinal cord program at the University of Louisville, said it would discontinue support of the Baclofen study.

NIDILRR based its decision on a review of the IRB audit, along with information from the federal government’s Office of Human Research Protections, which had made its own inquiry into Harkema’s work. Low numbers of study participants, poor documentation, and lack of ability to parse study participants’ records all contributed to its decision to discontinue funding.

The Baclofen study was in its last year when NIDILRR made its decision. At that point most of the funding had been spent, so NIDILRR asked the university to redirect any unspent funds to other spinal cord injury work at the university that it was funding. That totaled about US $147,000, according to Harkema.

Terminating funding of an ongoing study is not unprecedented at NIDILRR, but it is unusual. “It doesn’t happen most years,” says Christine Phillips, a spokesperson for NIDILRR’s parent agency, the Administration for Community Living.

The U.S. government’s Office for Human Research Protections is still reviewing the Baclofen study.

Harkema says she takes full responsibility for the documentation errors. The data her group collects on study subjects are in the terabytes, and had to be spread across several computers, which led to the disorganization, she says.

Harkema says her group has fixed those problems, and implemented every change requested by the IRB. “We modified our standard operating procedures in response to every request and they are now implemented for all of our [group’s] ongoing studies” including those that were not audited, Harkema says. The studies are stronger now as a result, she says.

The IRB’s audit of Harkema’s work was prompted by complaints from two of her former colleagues at the university who alleged that the safety of the patients enrolled in the studies was at risk.

The IRB’s audit, however, concluded for each of the four studies that “allegations concerning subject safety were unfounded.”

Emily Waltz is a features editor at Spectrum covering power and energy. Prior to joining the staff in January 2024, Emily spent 18 years as a freelance journalist covering biotechnology, primarily for the Nature research journals and Spectrum. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Discover, Outside, and the New York Times. Emily has a master's degree from Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and an undergraduate degree from Vanderbilt University. With every word she writes, Emily strives to say something true and useful. She posts on Twitter/X @EmWaltz and her portfolio can be found on her website.