By 1888, photographers had been fixing images on plates for more than six decades, and some of them produced impressive portraits, photojournalism, and landscapes. But no one could do such things easily.

The first prerequisite for effortless picture taking came in 1871, when Richard Maddox invented highly sensitive dry plates—glass coated with gelatin emulsion. That step eliminated the awkward coating-exposure-processing sequence that had to be done on-site when using the wet-plate process.

But an entire suite of improvements still needed to be made, and they came from an unlikely innovator: George Eastman, a bank clerk in Rochester, N.Y. In 1877, Eastman bought a camera and wet-plate gear to use on a trip to Santo Domingo. The trip fell through, but it prompted Eastman to experiment with new emulsion coatings, and in 1879 he patented a coating machine. In 1884 he replaced the glass support with a negative stripping film made of three layers—paper, soluble gelatin, and gelatin emulsion. In 1885 he added a convenient roll holder.

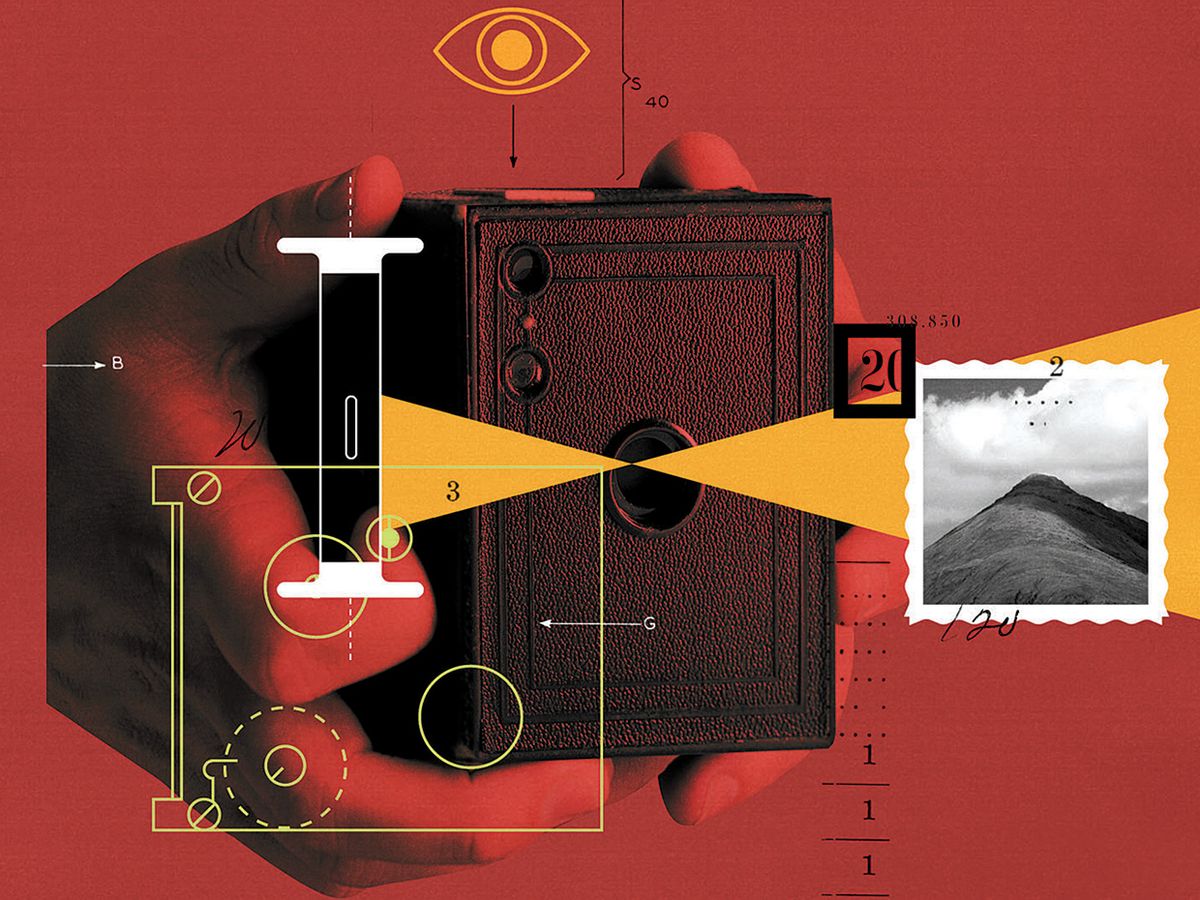

The final step came 130 years ago, on 4 September 1888, when Eastman was awarded U.S. Patent No. 388,850 for a small, handheld, easy-to-use camera. His company had already begun making it three months earlier.

Eastman called the camera a Kodak because he liked the ring of it. It was a wooden rectangular prism 9.5 by 8.3 by 16.5 centimeters (3.75 by 3.25 by 6.5 inches) covered in smooth black leather. Its 57-millimeter lens had good close-focusing capabilities, allowing the photographer to focus on objects as close as 1.2 meters.

It wasn’t really as easy to use as its advertisements claimed—“You press the button, we do the rest”—but it was easy enough. You put the film in and advanced it, and after exposing all 50 or 100 frames (there was no exposure counter), you rewound it. Then, you had to ship the entire camera to Eastman’s factory in Rochester to be developed and printed. The first model cost US $25 (more than $600 in 2018 terms).

Before the century’s end, the product line included, for the first time, film for a non-Kodak camera: the miniature (5 by 4 by 4 cm) Kombi pocket camera, with 25 exposures and a price of about $3.00. Also added were the Bull’s Eye camera, which allowed users to remove the exposed film in daylight and develop it at home, selling for $7.50 or so, and (in 1897) the Folding Pocket Kodak camera, the prototype of the roll-film designs that dominated the market over the next six decades.

Kodak kept its technical leadership by introducing the first safety film (made of cellulose acetate, rather than of highly flammable cellulose nitrate) in 1908. Amateur movie cameras followed in 1923, the first 35-mm precision Kodak Retina cameras in 1934, the first slide projector in 1937, Kodacolor film in 1942, and the Kodak Instamatic in 1963. That line of cameras sold more than 50 million units by 1970 making it the most successful tool of mass-scale amateur photography. I owned one.

Impressively, it was Kodak—the master of film—that in 1975 invented the world’s first digital camera, a toaster-size contraption with a resolution of 10,000 pixels. Yet although it kept a competitive position in this new filmless business for a while, it eventually lost the contest.

In 2012, Kodak entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy and sold all of its consumer and digital imaging patents for a mere pittance. The reorganized company, focusing on diverse imaging solutions (including instant-print cameras and 3D printing), is still around, but its stock has recently traded about 75 percent below its 2014 postbankruptcy peak. A brand that embodied generations of innovative American technical leadership has become yet another entry in the country’s manufacturing retreat.

This article appears in the September 2018 print issue as “September 1888: Kodak Camera is patented.”