The Rise of Robot Warriors

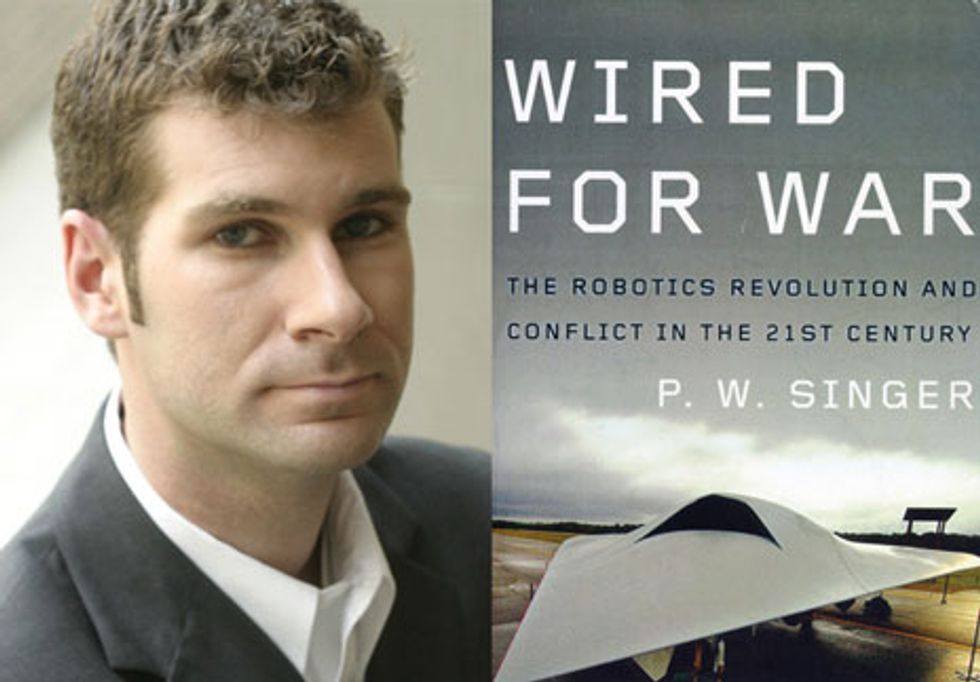

Author Peter W. Singer discusses how the United States is remaking warfare using robots

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have seen the unprecedented rise in the use of robots by the United States both on and above the battlefield. Peter W. Singer, the director of the 21st Century Defense Initiative and a senior fellow in foreign policy at the Brookings Institution, has been tracking these changes and their impacts. He focuses his research on three core issues: the future of war, current U.S. defense needs, and the future of the U.S. defense system. Singer’s most recent book, Wired for War: The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century (The Penguin Press), takes a deep and broad look into the history and future of robotics and warfare. IEEE Spectrum Contributing Editor Robert N. Charette recently spoke to Singer about how robots are not only changing warfare itself but also the politics, economics, and ethics that surround warfare.

IEEE Spectrum: Reading Wired for War, I was struck by how much is out there about the massive social implications of using robots on the battlefield today but also that this information seems to be flying under the public’s radar.

Peter W. Singer: In my introduction, I say I wrote this book because “mine is a generation that is producing more history than it can consume.” There is too much going on. It is hard to stay abreast of the day-to-day events, let alone the broader trends. You just have these amazing changes happening, and yet we don’t talk about them—sometimes because it’s too complex, sometimes because it’s almost too daunting, sometimes because, you know, we’re humans and we would rather just talk about ”American Idol.”

There is also the problem of our ignorance, almost willfully so. I had this remarkable experience during the book tour that really encapsulates that. I gave a talk and one of the people in attendance was a very senior Pentagon adviser—very senior, big name—who afterward was telling me about how really remarkable this was, he never imagined we had so many robots that we’re already using today, wow, he just didn’t know all this. As he is saying this, I am thinking, ”You’re the one who is helping shape the decisions on how to use them, you’re influencing funding for them, and yet you’re saying you weren’t aware of it.”

But that is not actually the thing that’s notable. He then went on to say, ”You know, this technology is coming so quickly that I bet that one day the Internet will be like in a video game with three dimensions and you’ll be able to walk around in it.”

I tell this story because my wife actually works for Linden Lab [the developers of Second Life]. I’m thinking in my head that he’s using the phrase ”one day” as if it is not even in three or five years’ time; it is the way we talk about ”one day we will live on Mars.” In his mind something like Second Life or virtual worlds is something way off in the fantasy world of one day, whereas it’s already five years old.

You don’t even have to be a really tech-savvy person to have known about it; it’s been featured on the television shows ”CSI” and ”The Office.” You just have to be tuned in to pop culture. Yet to him this is a thing that will never, ever happen. That just really struck me as the disconnect that we often have, including those in positions who really drive change the most, ironically enough.

Spectrum: I have a book by Alvin and Virginia Silverstein, published in 1983, called The Robots Are Here, which speaks of 1983 as being the year of the robots. It describes robots in factories, medicine, and the home, but there is absolutely no mention of military uses of robots. What has caused us to switch from looking at robots as toys to indispensable military hardware?

Singer: Throughout the history of war, it often is not what is technologically possible that matters the most; it’s what is viewed as bureaucratically imaginable and seen by soldiers in the field as battlefield useful. So look at the example of the machine gun; it was invented in the 1860s. We don’t actually start using it really until World War I, and even then it takes several more years of warfare before senior generals go, ”Hold it: This thing really does matter; it really is changing the way we have to fight.” Every technology has that.

So for robotics, it’s the experience post 9/11 and especially in the Iraq War. That’s where you have, I remember, one of the executives at the robot companies describing how you had people in the Pentagon who wouldn’t return their calls, and then, it’s like a switch had flipped; they are being told by those same people to ”make them as fast as you can.”

Each robotic company has their own moment like that. For iRobot, with the PackBot [a ground-based military robot], it happens when they finally get the prototypes into the hands of soldiers in Afghanistan and when the soldiers in Afghanistan won’t give them back at the end of what was supposed to be a couple of weeks of experiments. In the very first iteration of the U.S. Army’s Future Combat Systems [a $159 billion modernization program], there’s no small ground robotics in it. Now, with the new Obama administration defense budget, FCS is being gutted—except for this part [small robots] that was never part of the original plan. [Editor’s note: The entire FCS program was officially terminated on 24 June 2009]

Foster Miller [a high-tech company in Waltham, Mass.] talked about their ”ski-ski” moment in Iraq, where basically they had been able to get the robot systems out to the EOD [explosive ordnance disposal] teams, but the teams weren’t using them. The EOD guys are incredibly brave and were leaving the robots in the back of their vehicles. The ”ski-ski” moment is this tragic incident that happens over the course of a couple of days where two EOD techs are killed in Iraq, and both of them are of Eastern European heritage with last names ending in ski. And suddenly, it went from ”We leave the robots in the back of the truck” and ”We don’t use them because we’re brave” to ”You know what? We really do have to start using them.”

There are other similar experiences for all sorts of unmanned systems, such as with the [General Atomics MQ-1] Predator UAV drone, where you go from no one wants them to the top general in CENTCOM [United States Central Command] describing them as ”my most valuable weapon”—not ”my most valuable unmanned weapon” but ”my most valuable weapon overall.”

Spectrum: In the Unmanned Aircraft Systems Roadmap, the Department of Defense said it hoped—and I think most people thought then it was a fantasy—to have around a total of 350 unmanned aerial vehicles in the military inventory by 2010. How may UAVs are in the U.S. inventory today?

Singer: Let’s pull back and not just talk about UAVs. Overall, the numbers are evidence of why we are living through such an important moment where science fiction really is becoming battlefield reality, and why this story is important, not only to war but maybe to humanity itself.

We go into Iraq with literally a handful of drones and the U.S. military inventory. All of Fifth Corps [which led the advance into Iraq during the invasion from the desert west of the Euphrates River] has one drone supporting it; we now have over 7000 in the U.S. military inventory. On the ground we go in with zero used in the invasion force; we now have over 12 000, and the growth curve appears to be continuing to be exponential. It’s zero in 2003, it’s 150 in 2004, and by 2005 it is 2400; I spoke with an Air Force three-star general who says we are soon going to be talking about ”tens of thousands” in our conflicts.

These numbers are remarkable, but you have to think about them in a couple of ways. One is that these are the earlier models; these are Model-T Fords or Wright Brothers fliers in comparison to what’s coming. It’s interesting that in comparison to World War I, the number of UGVs [unmanned ground vehicles] we have today is about the same number as the British had tanks at the end of the war.

The next part of this to remember is that the capability of these systems and the applications they are being used for is going up exponentially. If the idea of Moore’s Law continues to hold true, then 25 years from now these systems will be as much as 1 billion times as powerful as today’s in terms of their computing power. Now if that is not true, if they are only one-hundredth as much, then they will be ”merely” a million times as powerful.

That leads to the second thing, which is that technologies are revolutionary not only because of the incredible new capabilities they offer you but because of the incredible new questions they force you to ask—questions about what’s possible that was never possible before and also new questions about what’s proper, what’s right or wrong that you didn’t have to think about before. That’s really what the book is about.

It is about going around meeting all these people, from the robot scientist who wonders if he is equivalent to the nuclear physicist back in the 1940s, to the science fiction author who is now actually having a major impact on what’s being made and done in the real world, to the 19-year-old drone pilot sitting in Nevada who is now flying a system over Pakistan. All the experiences of war are fundamentally different for him than they were for every single generation of soldiers before. He’s experiencing war, but he is not experiencing any risk.

It goes to the officers who are commanding robots; it is largely different from commanding people. It may be silly to say that, it’s so evident, yet it’s no longer a science fiction question. It goes to politicians, where it is affecting when and where we decide go to war.

What Wired magazine calls the ”robot war in Pakistan” right now is a good illustration of that. We have carried out as many strikes in Pakistan last year as we did in the opening rounds of the Kosovo war. We didn’t debate about it in Congress like we did the Kosovo war, because I would argue it’s riskless, but just to us. But the other side of this is that it affects how people look at us: people in Pakistan, people in Lebanon, it affects how the insurgents look at us.

When you do have this act of force, but [you’re] not going in harm’s way, that raises all sorts of new questions about accountability and the laws of war. That’s what makes this revolutionary, what makes this equivalent to the printing press, the computer, the atomic bomb.

Spectrum: The IEEE just celebrated its official 125th anniversary. Given the direction of robotics, what advice would you give engineering students who are interested in robotics about what they need to be studying?

Singer: You need to have a really multidisciplinary background. Engineering can no longer operate in blissful isolation and in blissful ignorance of other fields. And this is not just crossing into other hard sciences such as engineering and biology, which is leading to the field of bioinspired robotics. It also crosses into the social sciences and, more broadly, the humanities. I think a major area needed is a better understanding of law and ethics.

The very definition of a robot is that it has sensors, processors, and effectors. A robot’s effectors create change in the world. They are the parts of the robot that, as one scientist put it, ”create drama.” Well, dramas can be enjoyable or heartrending. By their very definition, robots create change in the world.

About the Author

Robert N. Charette, an IEEE Spectrum contributing editor, is a self-described ”risk ecologist” who investigates the impact of the changing concept of risk on technology and societal development. Charette writes Spectrum Online’s Risk Factor blog.