27 April 2011—When the twin Voyager space probes launched nearly 34 years ago, they captured imaginations (and spawned the first Star Trek movie plot) by carrying a high-tech greeting card from the human race—a gold-plated phonograph disc with descriptions of humans, greetings, and Earth's location.

With the Voyagers now speeding through interstellar space, NASA will host a panel on 28 April to discuss the project's scientific and philosophical impact. The discussion will stream live at 1:00 p.m. eastern time on both the NASA and Jet Propulsion Laboratory sites.

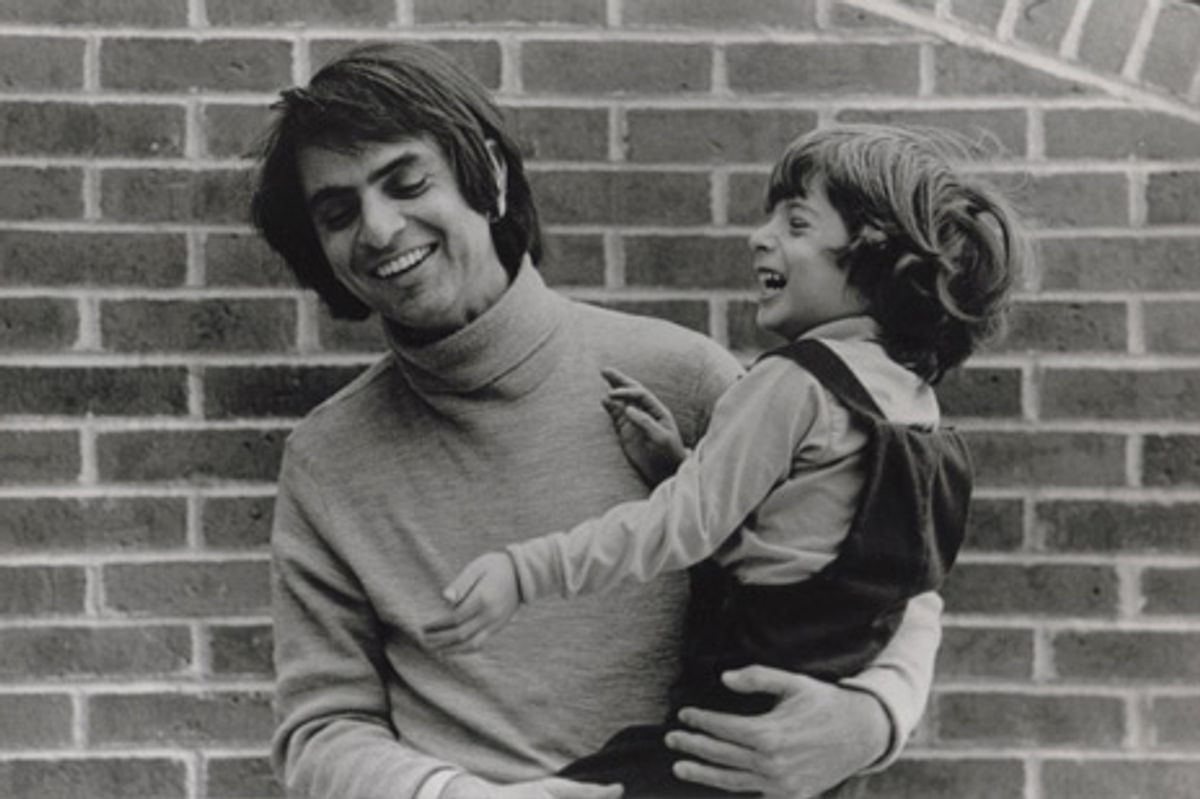

Voyager's extraterrestrial invite was spearheaded by the late astrophysicist Carl Sagan. Nick Sagan, Carl's son, was only 6 when he recorded "Hello, from the children of Planet Earth" on the disc. Today he's an award-winning science fiction writer, best known for his work on TV's "Star Trek: Voyager" and the Idlewild book trilogy. His graphic novel series, Shrapnel, is in development for a film and video game, and he has a deal for a show on the Science Channel. Here, Sagan—who spoke to Spectrum Radio last year—talks about how Voyager inspired him.

IEEE Spectrum: What do you remember of the Voyager project?

Nick Sagan: It was very quick and mysterious to me. There were greetings in many different languages on the disc, and my folks thought it would be nice to have a kid represent one. My dad plopped me down in front of a mic in a room at Cornell University, where he taught, and asked me what I would want a visiting extraterrestrial to know. I came up with "Hello, from the children of Planet Earth."

IEEE Spectrum: None of it struck you as odd?

Nick Sagan: These questions were normal in my home. When your dad is an astronomer, there's a certain focus on this. We'd go out and look at the stars, and there were often astronomers and science fiction writers, like Isaac Asimov and Ray Bradbury, over our house for dinner.

At the time, I was too young to fully understand what Voyager was. But now I'm humbled to be part of it. There's a possibility that a piece of me will exist long after I'm gone and the Earth ceases to exist. It's a kind of immortality.

IEEE Spectrum: How did Voyager and your father inspire your writing?

Nick Sagan: Voyager is an attempt to communicate with the universe and articulate our biggest questions and deepest yearnings: Are we alone? How did we get here? It was reaching out and hailing the universe in friendship—a message in a bottle cast upon the cosmic tides.

When I was a kid, my dad and I would talk about those questions. He was a more positive person, so he could look at both sides, recognize the challenges for our species, and ultimately bet on us. Often I would play devil's advocate. As I write, I continue those conversations in my mind as a means of holding on to him.

As technology gets more powerful, there's an ability for fewer people to do more damage, so an important question is whether we can triumph over our darker impulses. I feel like there's a responsibility as a science fiction writer to point out areas where things might break or go wrong. It's analogous to being a scout in a primitive society.

IEEE Spectrum: Given human behavior, is it such a good idea to try to contact other intelligent life?

Nick Sagan: For decades, all of our broadcasts have been soaring out into space—and at the speed of light, which is much faster than Voyager. Those are more likely to be intercepted first. So if something nasty shows up, blame the media!

A more sobering thought is that SETI [Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence] has spent years searching for signals indicating intelligent life, and all they've found is silence. Is that because intelligent species cross a certain technological threshold and self-destruct? I wonder if there are other "Voyagers" out there, other messages in bottles drifting through the cosmos, sent in the hopes of being remembered.