As an engineer, I found the current best-selling novel All the Light We Cannot See nostalgic and thought provoking. The story is about a young German boy, Werner, and a blind French girl, Marie-Laure, during the German occupation of France in 1939.

Before I read the book I assumed that the title had to do with the blindness of Marie-Laure, but instead the title refers to radio waves, as illustrated by this passage from the book: “What do we call visible light? We call it color. But the electromagnetic spectrum runs to zero in one direction and infinity in the other, so really, children, all of light is invisible.”

The author, Anthony Doerr, has said that his original motivation was to “conjure up a time when hearing the voice of a stranger in your home was a miracle.” The story portrays an era when families clustered around radios made by companies such as Philco and Grundig, when propaganda dominated broadcasts and radios were critical to both armies and resistance cells, when people twiddled the dials of shortwave receivers to search for voices from faraway cities, and when the music on the airwaves was Mozart and Bach.

The characterization of radio waves as invisible light interests me. Somehow I associate photons with visible light but not with radio waves. The very word “photons” seems to connote visible light. In most of classical electrical studies we deal instead with electrons—charged particles that have associated fields and, when they move, create waves. Maxwell’s equations describe it all, so there is no need to mention photons. But it is true that both visible light and radio waves are electromagnetic waves, and the associated particle is the photon.

When Werner is 13, he studies radio waves from Heinrich Hertz’s The Principles of Mechanics. (I’m impressed, since that classic text is dense with partial differential equations.) His affinity for the technology gains him a reputation for fixing radios, where he applies an unusual approach:

He dismantles the machine, stares into its circuits, lets his fingers trace the journeys of electrons. Power source, triode, resistor, coil. Loudspeaker. His mind shapes itself around the problem, disorder becomes order, the obstacle reveals itself, and before long the radio is fixed.

Werner usually ends up repairing a broken wire. I’m a little dubious about this, since bad vacuum tubes, melted capacitors, or burned resistors are more likely than breaks in heavy copper wires. Furthermore, I can’t imagine tracing circuits in an early radio by simply staring at the rat’s-nest wiring under the chassis. However, I don’t mean to quibble with the use of literary license. Tracing a circuit is a lot more impressive than replacing a vacuum tube.

Later, Werner joins the German army and operates direction-finding radio equipment, looking for resistance transmissions, including those being sent by Marie-Laure from her attic transmitter.

The book closes with Marie-Laure as an old woman in contemporary times, thinking about what has become of the radio waves that were so important to her and Werner during the war:

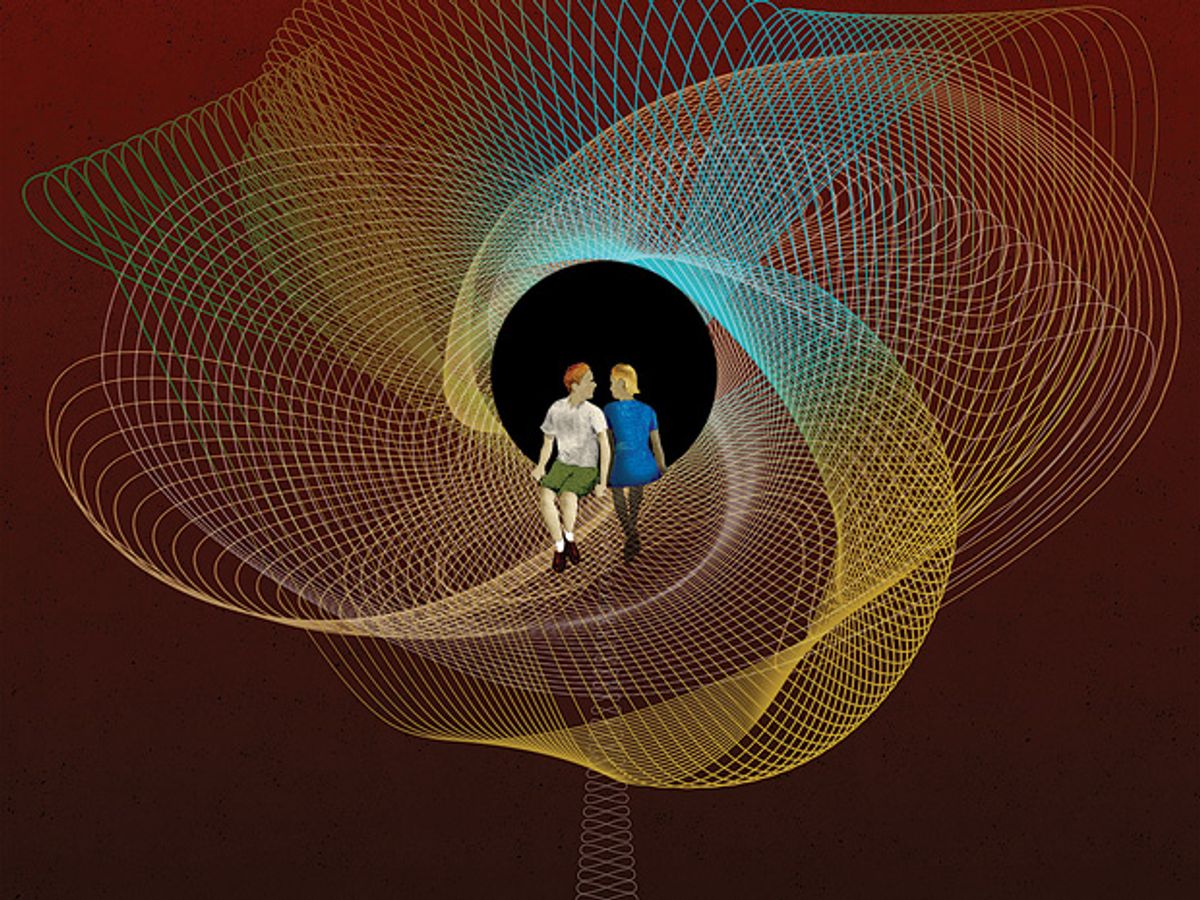

Marie-Laure imagines the electromagnetic waves…except now a thousand times more crisscross the air…maybe a million times more. Torrents of text conversations, tides of cell conversations, of television programs, of e-mail, vast networks of fiber and wire interlaced above and beneath the city, passing through buildings, arcing between transmitters...

What if our eyes were sensitive to radio frequencies? What a symphony of thrashing, undulating colors we might see!

This article originally appeared in print as “Seeing Radio.”

Robert W. Lucky is a contributor to IEEE Spectrum. An IEEE Fellow, he holds 11 patents and worked for many years at Bell Labs. Before retiring in 2002, he was vice president for applied research at Telcordia Technologies, in Piscataway, N.J.