Last week, at the International Symposium on Assessing the Economic Impact of Nanotechnology held in Washington, D.C., researchers from the Georgia Institute of Technology presented a paper about using lifecycle analysis to gauge the impact of nanotechnology.

In their presentation, Philip Shapira and Jan Youtie emphasized that any assessment of nanotechnology’s impact—economic or otherwise—must take into account the full lifecycle of the product.

“Compared to information technology and biotechnology, for example, nanotechnology has more of the characteristics of a general technology such as the development of electric power,” said Youtie, director of policy research services at Georgia Tech’s Enterprise Innovation Institute. “That makes it difficult to analyze the value of products and processes that are enabled by the technology.”

I couldn’t agree more and it’s a point myself and others have been making for years, initially to widespread skepticism: nanotechnology is not an industry; it’s an enabling technology. If that is understood, it begs the question why continue to assess it as though it were a monolithic entity, or condemn it as one?

I think the answer is hidden in the press release for this new report when Youtie comments: “Scientists, policy-makers and other observers have found that some of the promise of prior rounds of technology was limited by not anticipating and considering societal concerns prior to the introduction of new products. For nanotechnology, it is vital that these issues are being considered even during the research and development stage, before products hit the market in significant quantities.”

Because we now have the social science capability to do this sort of thing, it seems like we're willing to apply it to a field that defies quantification of any kind.

I'm also nonplussed by another of the researcher's observations. Youtie implies that nanotechnology began with large companies and is now migrating toward an ever increasing number of small companies. I suppose a statement like this probably should be couched in all sorts of definitions of terms, which might color one’s interpretation of what it was intended to mean, but to me it seems that the trend has been almost the opposite of this.

Sure, the IBMs of the world did have the research money to develop the key tools that enabled us to work on the nanoscale. But I remember back in 2001-2003 that there were a lot of small companies that discovered that they could produce a nanomaterial and believed that this somehow would miraculously constitute a business. They soon discovered that large chemical companies could quickly produce the same material in bulk and had the supply chain connections to make sure that the material got into products. As a result, we have seen a number of small companies that were initially exhilarated they could produce carbon nanotubes in their garage get swept up into the great consolidation of nanomaterials companies.

But let’s get back to the primary point of the paper, which seems to be that we need to not only look at the great things nanotechnology can enable but also at the costs it creates. This echoes one of the most cogent arguments that the Friends of the Earth (FoE) have raised thus far. Essentially, the FoE points out that nanotechnology has not yet delivered on its claims to enable cheap solar, hydrogen and wind power, but even if it could, the energy used to create the nanomaterials would result in a net energy loss.

In an example of how quickly things change in the field of nanotechnology, a week after I covered the FoE’s report I reported on research from MIT that demonstrated a process for producing carbon nanotubes that reduced emissions of harmful byproducts by at least ten-fold and could cut energy use in half. One week you have a cogent argument, and the next you’re behind the times.

While it may be difficult to predict nanotechnology's impact without conducting lifecycle analysis, trying to include those lifecycle considerations will be far more difficult, and make their accuracy short-lived.

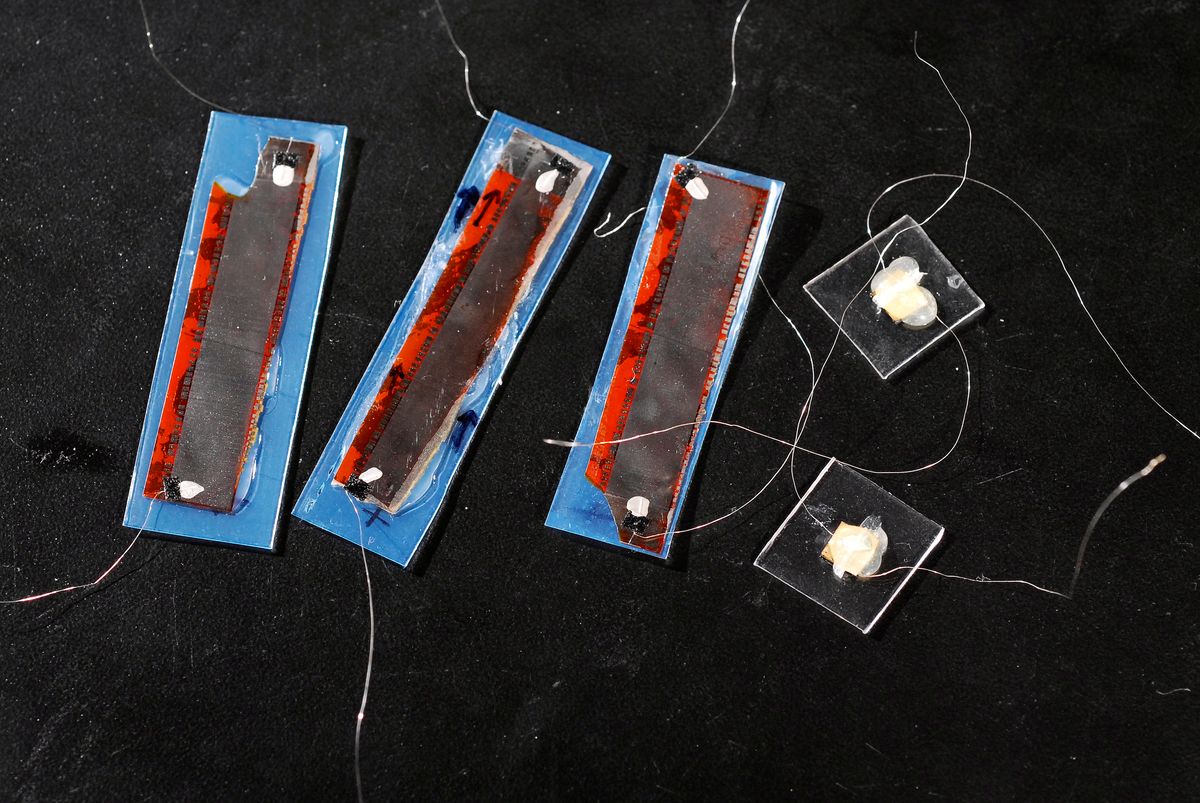

Image: Georgia Tech Photo (Gary Meek)

Dexter Johnson is a contributing editor at IEEE Spectrum, with a focus on nanotechnology.