Peter Parker gained the ability to sense imminent danger thanks to the bite of a radioactive spider. Now, in real life, researchers in Baltimore have enabled a rat brain to sense electromagnetic fields thanks to the gene of a catfish.

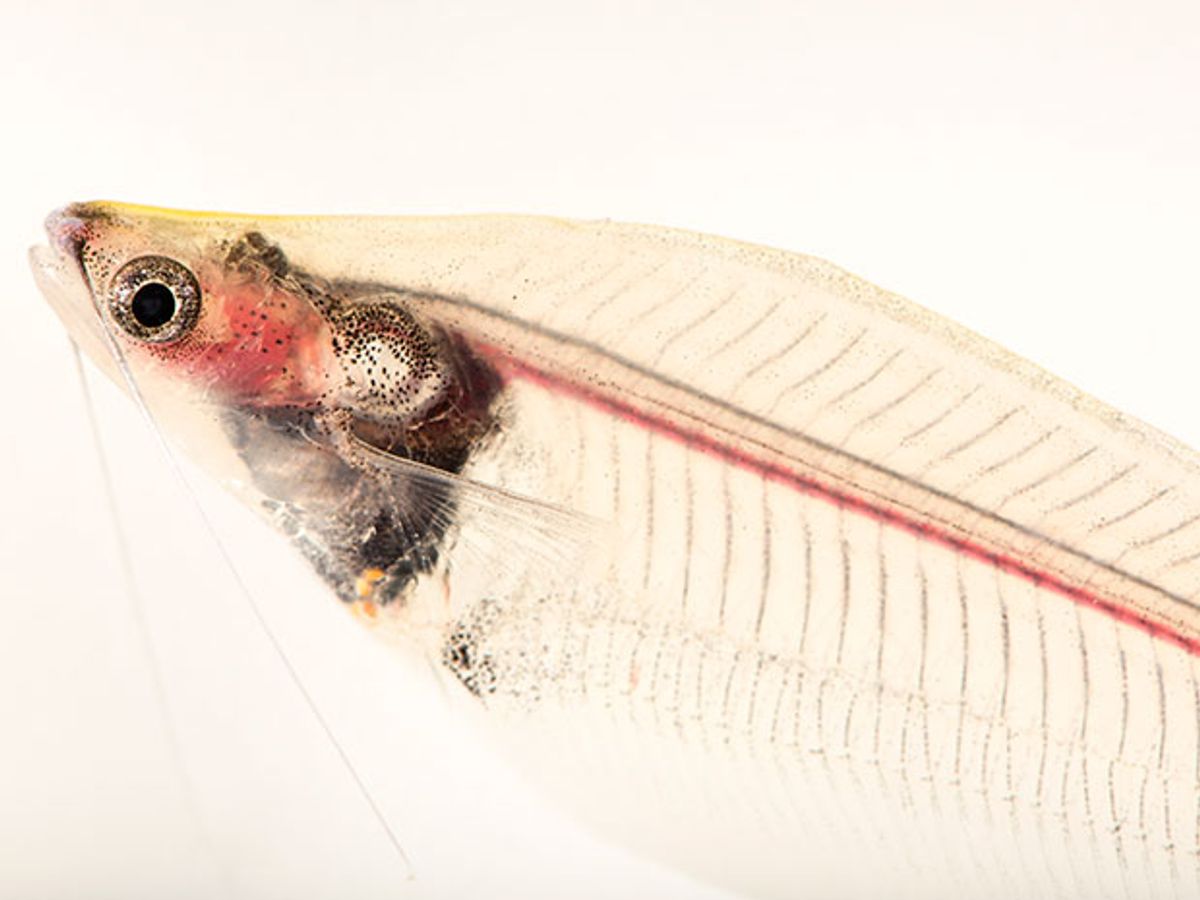

Many animals—birds, bees, lobsters, and newts, just to name a few—can sense the Earth’s weak magnetic field, but not humans. (There is some debate over that exclusion.) A newly discovered gene, belonging to the glass catfish, appears to give cells the ability to respond to magnetic fields and can be used to non-invasively manipulate brain and heart cells.

The researchers say the technique opens the possibility of creating wireless biological heart pacemakers, treating epilepsy, or even constructing brain-machine interfaces that use electromagnetic signals to communicate with human cells.

Galit Pelled, an associate professor at the Kennedy Krieger Institute and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, will present the work this Sunday at the 8th International IEEE EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering in Shanghai, China.Scientists have previously identified genes involved in electromagnetic sensing in pigeons and bacteria. Many of those genes work together to form molecular complexes that sense the magnetic fields. This new gene—the first found in a fish—is unique because it works on its own and is not associated with the formation of such complexes.

Pelled and colleagues originally found the gene by inserting various bits of DNA from the glass catfish (Kryptopterus bicirrhis) into frog eggs, and seeing which of the eggs responded to a magnetic field. They identified just one gene with that effect, and named it the electromagnetic perceptive gene (EPG).

How the protein encoded by EPG actually senses electromagnetic fields remains a mystery. “We don’t know exactly what the protein is doing,” says study co-author Assaf Gilad, an associate professor of radiology at Johns Hopkins Medicine.

But they do know the effect: When the protein binds to the surface of a cell, it causes a flood of calcium into that cell. For many cell types, including neurons and heart cells, that gush of calcium activates the cell, causing it to fire or beat. The team inserted the EPG gene in groups of brain cells, and then were able to wirelessly activate those neurons with an electromagnetic field. They also inserted the EPG gene into living rat brains.

That’s important because Gilad hopes the technique will someday be used to activate select parts of the human brain to ease conditions related to misfiring neurons, such as epilepsy and depression. Currently, doctors use invasive techniques such as deep brain stimulation to try to alleviate such illnesses. With EPG, they might instead deliver the gene—via gene therapy or stem cell transplants—into a patient’s brain and then wirelessly manipulate the cells. There is also potential for heart conditions, where a pacemaker made of cells expressing EPG could be controlled wirelessly, and not have to be replaced every 10 years, like traditional electronic pacemakers.

“The ability to remotely control neuronal activity is big,” says Gilad. Still, he notes, “this is a very experimental concept.”

Speaking of experimental, let’s get back to Spiderman. Could the tech be used to give mammals—say, humans—a sixth sense? “Maybe—I don’t know,” says Gilad. Right now, the team has only identified a single part of the catfish’s electromagnetic sensing ability. Once more is known about how it works, “Well, yeah, maybe sometime down the road, people could have their own GPS,” Gilad adds with a laugh. For now, the team is busy looking deeper at the fish system and investigating more immediate uses for the gene.

Megan is an award-winning freelance journalist based in Boston, Massachusetts, specializing in the life sciences and biotechnology. She was previously a health columnist for the Boston Globe and has contributed to Newsweek, Scientific American, and Nature, among others. She is the co-author of a college biology textbook, “Biology Now,” published by W.W. Norton. Megan received an M.S. from the Graduate Program in Science Writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a B.A. at Boston College, and worked as an educator at the Museum of Science, Boston.