When Google unveiled its unprecedented demonstration of quantum computational advantage over classical computing in late 2019, Chinese researchers reported progress toward their own milestone demonstration.

Just over a year later, the Chinese team has shown a different but no less exciting path forward for quantum computing by achieving the second known demonstration of quantum computational advantage—also known as quantum supremacy.

This new finding does more than just confirm that quantum computers can solve certain problems faster than conventional supercomputers. (That’s the “supremacy” part.) It also adds a surprising twist: It now appears possible to achieve phenomenal computational feats with lasers and nonlinear crystals. Photonic systems have sometimes been considered more of a bridge technology between quantum devices than the core of a quantum computer itself.

No longer.

“In October 2019, we were confident that we were very close to the quantum-advantage milestone,” says Chao-Yang Lu, a quantum physicist at the University of Science and Technology of China in Hefei.

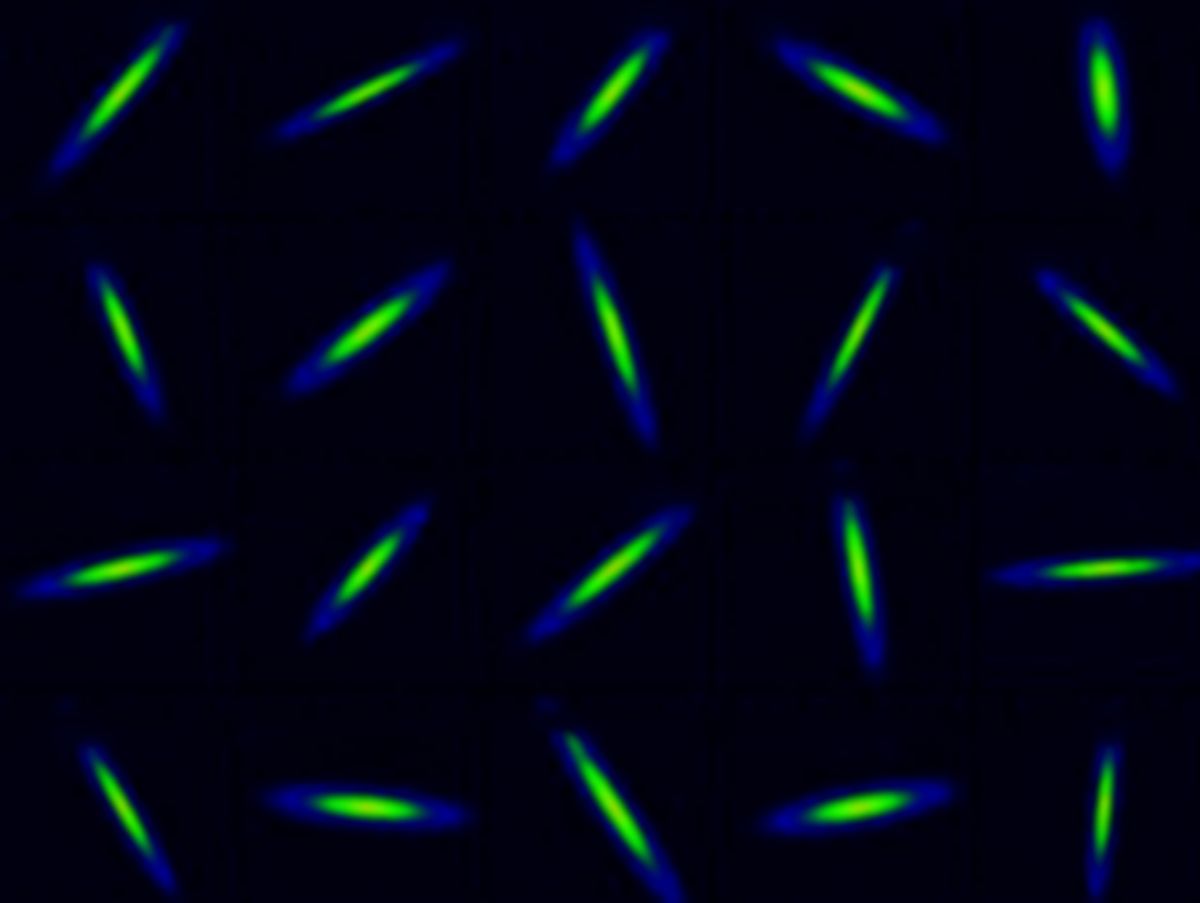

To reach that milestone this year, Lu and his colleagues engineered one of the most intricate versions of a light-based quantum computing experiment yet. It’s effectively a maze for identical photons to travel through depending on the photons’ quantum properties.

MIT theorists Scott Aaronson and Aleksandr Arkhipov first envisioned this kind of device in 2010. They called it a boson sampling machine.

This machine’s photon detectors could help figure out where the randomly distributed photons end up. Which is a very complex mathematical problem. And that is the kind of math problem that a classical computer bogs down over as the number of distributed photons increases.

In this case, then, quantum advantage or supremacy is achieved when even the fastest supercomputers take substantially longer to solve the photon-distribution problem than the quantum system takes.

Led by quantum physicist Jian-Wei Pan at the University of Science and Technology of China, the group built a large tabletop setup consisting of lasers as the light source and beam splitters to help create the individual photons, along with hundreds of prisms and dozens of mirrors to provide the randomized paths for the photons to travel.

That allowed the team’s quantum computing hardware, named Jiŭzhāng, to detect 43 photons on average during experimental runs lasting 200 seconds. By comparison, the world’s third-fastest classical supercomputer, Sunway TaihuLight, would require two entire days to calculate the distribution for 50 photons, according to the team’s paper, published in a recent issue of the journal Science.

Scott Aaronson, who is currently at the University of Texas at Austin, wrote a blog post in which he described himself as “gratified” by the Chinese team’s work. Other researchers who previously worked on earlier and smaller versions of boson sampling machines also praised the experiment.

“It really shows that it was superhard work, very impressive engineering, very impressive control, and a well deserved result at the end to justify publication,” says Philip Walther, a quantum physicist at the University of Vienna.

The new Chinese research differs from the Google team’s quantum supremacy claim in several key ways. Notably, Google’s 2019 demonstration with the 54-qubit quantum computer called Sycamore relied on a completely different architecture based on superconducting metal loops. Quantum computing hardware based on arrays of such superconducting qubits has gained traction among tech giants such as Google, IBM, and Intel.

Other companies such as Honeywell and IonQ have been developing alternative quantum computing architectures based on trapped ions. And in Australia, Silicon Quantum Computing has been developing quantum computers based on spin-based silicon qubits.

The Chinese team’s demonstration of boson sampling remains a fairly specialized experiment designed for proving quantum-computational advantage over classical computing rather than having immediate practical applications. That makes its uses far more limited for now than those of Google’s Sycamore quantum processor, which is designed to be programmable for many different applications.

“One of the challenges with this great demonstration is it’s not programmable,” says Christian Weedbrook, founder and CEO of the Toronto-based quantum-computing startup Xanadu. “In terms of applications you do need to have a full programmability, and this has no programmability.”

A few companies have already been developing photonic quantum computers that may be closer to commercialization, even if they have not yet publicly achieved the Chinese team’s scale. The Palo Alto startup PsiQuantum has remained in stealth mode while raising at least $215 million from investors to develop their own version of a photonic quantum computer.

For its part, Weedbrook’s startup Xanadu has been developing a programmable version of photonic quantum computing based on integrated silicon photonics that could fit on a computer chip rather than a tabletop. Certain applicants can already access 8- and 12-qubit versions of Xanadu’s machines through a cloud service—and will soon also have access to 24-qubit machines.

“We have a goal of demonstrating [fully programmable] quantum supremacy using our approach...sometime next year,” Weedbrook says.

Engineering hurdles remain on the path to commercializing large-scale photonic quantum computing, says Matthew Broome, a quantum physicist at the University of Warwick, in England, despite the apparent success of the Chinese experiment.

“While these experiments are superimpressive—and without a doubt some of the most complex optical systems ever constructed—if we are to take photonic quantum computers to the next level we need to solve the issue of loss and detection for integrated circuits,” he says. “The required engineering here is probably closer to materials science than it is [to] quantum science.”

Still, the Chinese team’s demonstration has given researchers cautious but renewed optimism about photonic technology as a viable road for developing practical quantum computing—especially after many had assumed such large-scale photonics demonstrations would struggle to become a reality.

“Photonics was always in the race, but I think that the press [coverage] and the dominance of ion-trap and superconducting quantum computers was very strong,” Walther says. “So now photons are back.”

Jeremy Hsu has been working as a science and technology journalist in New York City since 2008. He has written on subjects as diverse as supercomputing and wearable electronics for IEEE Spectrum. When he’s not trying to wrap his head around the latest quantum computing news for Spectrum, he also contributes to a variety of publications such as Scientific American, Discover, Popular Science, and others. He is a graduate of New York University’s Science, Health & Environmental Reporting Program.