Besides its cute little green robot mascot, what is it about Android that makes it so popular among device manufacturers and developers alike?

In a word, openness.

For developers, Android's license lets them get right into the heart of the platform's code, without signing their creative lives away. Android is based on open source software, allowing both collaboration (among disparate developers) and customization (of one's own offering). Neither is easily done on iOS, Apple's operating system for its iPads, iPhones, and iPods. Hardware manufacturers appreciate the open nature of Android, too. Android falls under the stewardship of the Open Handset Alliance, a consortium of device makers, mobile operators, and semiconductor, software, and other suppliers.

This openness, though, leads to some problems for both customers and developers. Because designers are allowed to modify Android to suit their needs—which they often do, in the hopes of differentiating their devices from those of other Android makers—different Android tablets can do the same thing in different ways. For example, configuring network settings is a rather different procedure on Samsung's and Archos's tablets, even if you're setting up the same network. Worse, the programming environments that manufacturers come up with for developers can also vary. HTC Corp.'s menus are different from those of their Motorola counterparts, for example, and the ways windows are managed can differ as well. That makes it harder to move from one tablet to another, which is presumably one of the selling points of a single OS. Imagine, for example, the Windows File menu being different on a Dell computer and a Lenovo one.

Yet so far, this fragmentation doesn't seem to be hurting the platform. Android now outsells Apple in smartphones and will do so in tablets, and its primary commercial sponsor, Google, often touts the more than 50 000 apps available for Android. (To be sure, nearly all were designed with smartphones in mind, but that will soon change.) Unlike Apple, which uses its App Store to control which apps are permitted on iOS devices, Android's alliance lets developers create and deploy whatever applications they like, as fast as they'd like. Of course, it's not all a bed of roses: That same free environment has led to applications that are sketchy at best and dangerous at worst. Luckily, the Android community is self-correcting, and such apps don't last long in the light of day.

Unlike iOS, which runs only on Apple's proprietary hardware, Android gives tablet makers hardware flexibility—different processors, for example—and interface options, such as how to sync with a computer.

Of course, more choices mean more caveats for consumers to emptor. So here are some things to look for when considering an Android tablet.

The version. Android's latest release is Android 3.0—its dessert-oriented code name is Honeycomb—and it will be in all the new tablets from the Motorola Xoom onward. Look for Ice Cream Sandwich Android devices in the latter half of 2011. Android 3.0 is the first tablet-specific version, which is why we're only now seeing applications that take advantage of a tablet's size and interface.

Flash or no Flash. Unlike iOS devices, Android devices will run Adobe Flash. But it's a mixed blessing, as running Flash movies depletes power rapidly. Apple is relying on HTML5 as its video standard, and you may want to do so as well.

Application store. Google, the commercial sponsor of Android and its strongest developer, has put together a very good app store, known as Android Market. Hardware vendors usually use some form of Market to enable users to download and buy Android apps. Do some digging and see how many apps are really available for that device. Check especially how many tablet-friendly apps are available—the overall number of Android apps specifically made for tablets is very small. Fewer than 50 were available at press time.

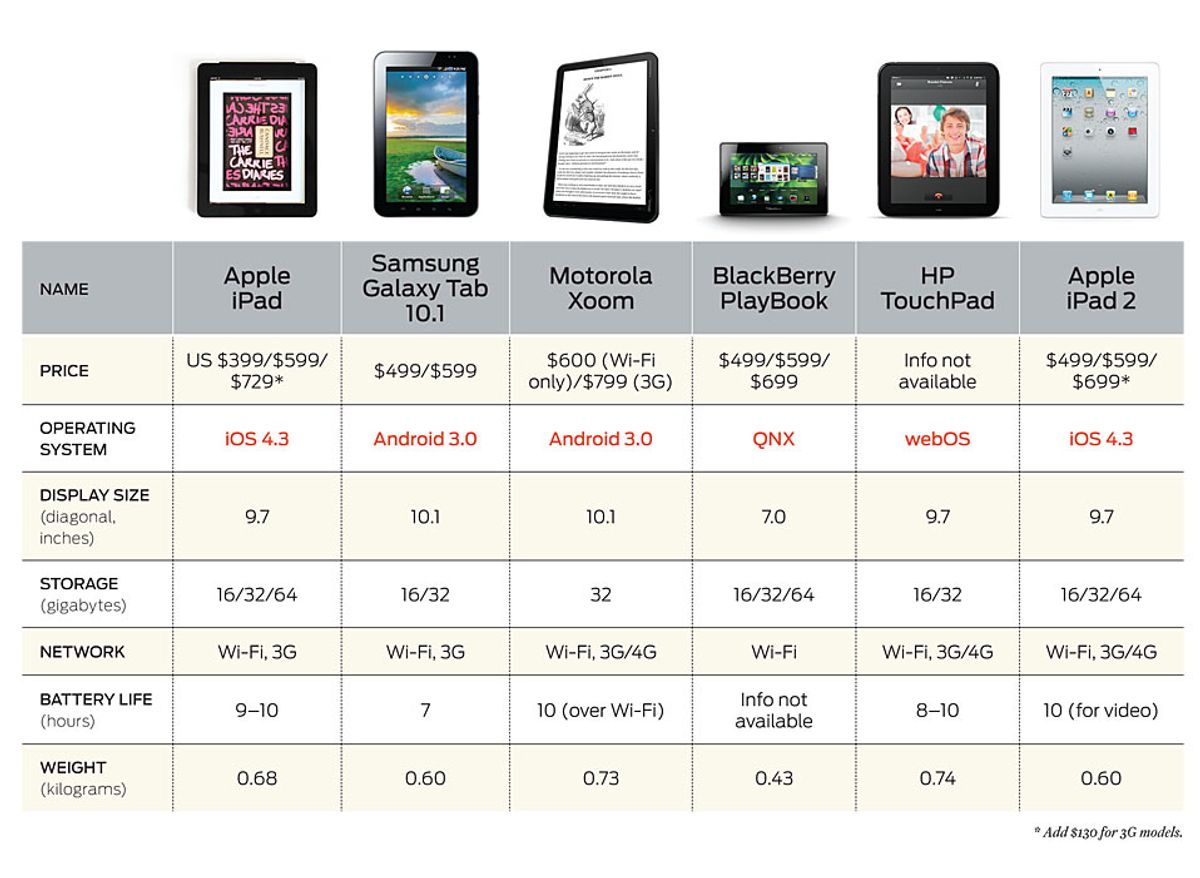

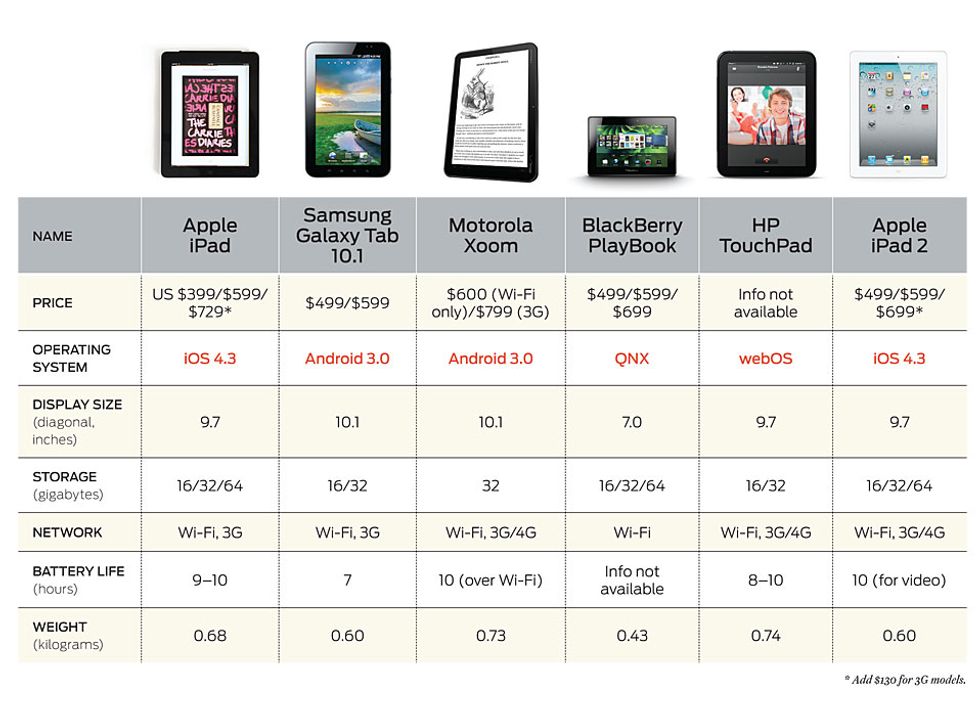

Because of Apple's and Samsung's early success with the iPad and Galaxy Tab, respectively, many new tablets are staying fairly close to these pioneering products' price, capacity, and capability. Based on all the leaked information as of early April, expect to see these similarities between devices:

- An average price of around US $613

- A screen size of about 9.7 inches, diagonal (25 centimeters)

- 32 gigabytes of storage capacity

- At least Wi-Fi and optional or included cellular connectivity

- About 10 hours of battery life (for video playback)

- An average weight of 0.6 kilograms

- At least one camera

The most dramatic differences are in the operating systems. While Apple devices will remain forever true to iOS, and all the other existing tablets use a version of Android, HP's upcoming TouchPad will support webOS (which, like Android, is derived from Linux via Palm smartphones), while the Research in Motion (BlackBerry) PlayBook will sport QNX, a 20-year-old Unix operating system newly transported to mobile devices.

The different operating systems will manifest themselves in the hardware, the look and feel of the interface, and the application ecosystem available for the devices. Both iOS and Android already have well-populated app stores, in part benefitting from their earlier presence on mobile phones. QNX and webOS also have a history from BlackBerry and Palm devices, respectively, but it will take a while to see how strong developer interest is in rewriting their smartphone apps for tablets or coming up with new ones. At press time, both the PlayBook and TouchPad are still in rumor mode, and there's always the chance RIM or HP will push out something truly unexpected for the devices' expected releases this spring.

Then there's the iPad 2, released back in March. Apple held steady on prices, but the memory capacity and number of cores doubled, while the number of cameras went from zero to two and cellular networking went from three to four—3G to 4G, that is.

About the Author

Brian Proffitt is an adjunct business instructor at the University of Notre Dame and has written 19 books on consumer technology and one on the philosopher Plato. His latest, Take Your iPad to Work, was published in October.