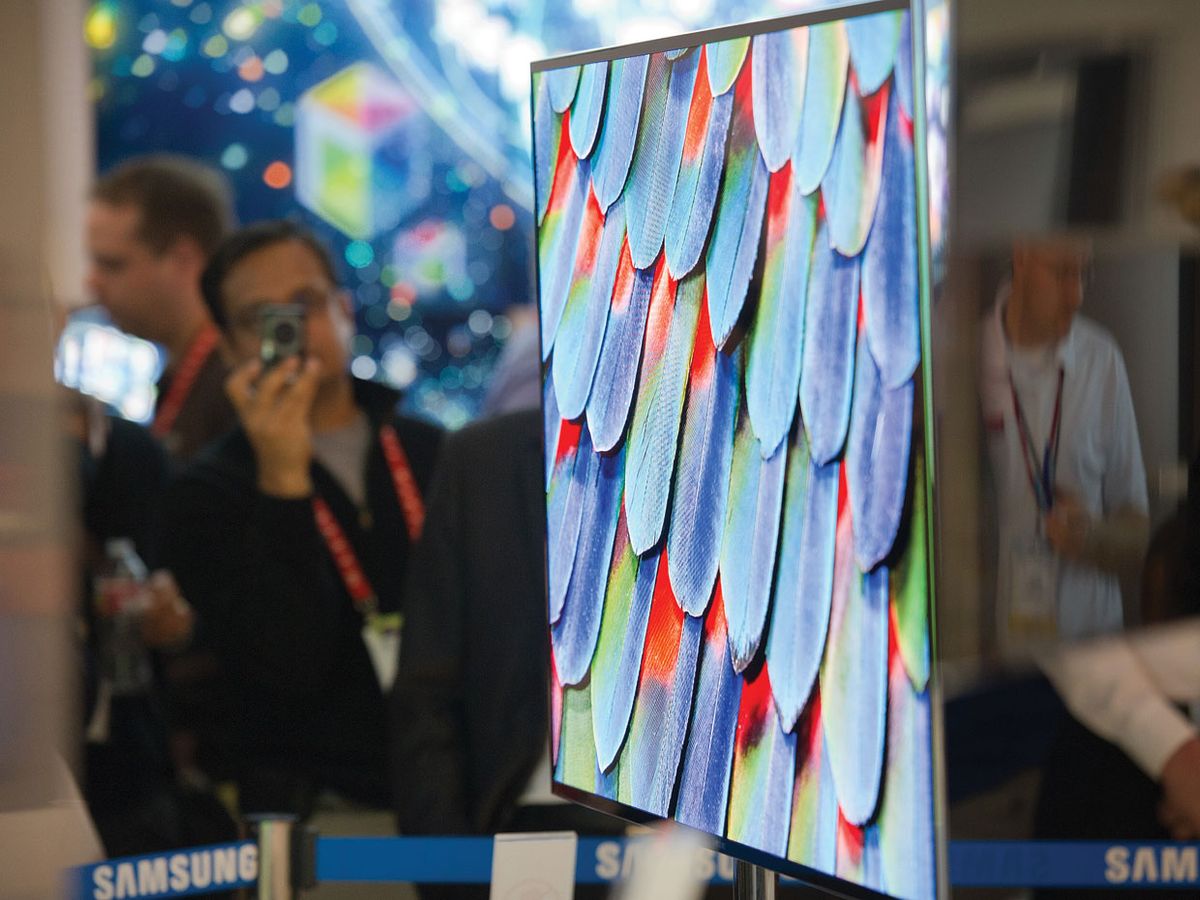

OLED TV Arrives

New displays will be big, bright, fast, and thin—but not cheap

For the past decade, two television display technologies—liquid crystal and plasma—have fought for supremacy, and although the LCD won the battle, it is about to lose the war. A third contender’s star is rising: the organic light-emitting diode, or OLED.

The thin, bright, beautiful, low-power OLED has been shining from the occasional cellphone or digital camera for several years now, but manufacturing problems kept its cost too high and its effective lifetime too short for consideration in big-screen TV.

This year, however, at least four major manufacturers think the time is right to sell 55-inch sets to consumers with cash to spare and an urge to own the latest and greatest gizmo. In a few years, OLED will reign supreme—at least until the next big technology comes along.

First, a brief review of the technology. OLEDs are semiconductors made of layers of organic material. They create light in much the same way as a traditional LED does: Electrons and holes meet and cancel each other out, releasing photons. Manufacturers make the screens by spraying organic films onto a substrate, typically glass or plastic, printing out patterns the way ink dots are printed on paper.

An LCD TV needs a backlight, but an OLED’s pixels emit their own light. So turning them off makes them go completely black, with none of the afterglow you’d get from phosphor-based technologies—like cathode-ray tubes or plasma displays—or even from an LED-backlit LCD, which can dim only regions of the screen, not individual pixels. Being able to create a really black black greatly improves picture quality.

And screens without backlights can be made very thin. Korean consumer electronics manufacturer LG has announced that its first 55-inch OLED TV will be just 4 millimeters thick and weigh 7.5 kilograms. A comparable 55-inch LCD TV from LG is nearly 4 centimeters thick and weighs about 22 kg.

OLED pixels can also be tiny and dense. Today’s high-definition TV contains a grid of 1920 by 1080 pixels; broadcasters and manufacturers, however, are already talking about ultrahigh definition, or 4K resolution TVs, which typically boast 3840 by 2160 pixels. An OLED can manage that easily.

And OLEDs can switch on and off quickly enough to keep up with fast-moving images, which even the best LCDs tend to smear.

Finally, because they’re printed, OLEDs can, in principle, be fabricated on flexible plastic substrates. Paul O’Donovan, principal research analyst for Gartner’s semiconductor research group, says this could happen in as little as five years. He envisions a giant, wall-mounted TV screen that rolls up when not in use, so that it won’t dominate the living room.

So far OLED screens have come only in small sizes, because manufacturing complexities ruined too many large screens, raising their unit cost. Over the years, companies have lowered the defect rate and have increased screen life by extending the time it takes for the blue pixels to fade to half their original brightness. That metric has risen from 5000 hours a few years ago to about 34 000 hours today at typical TV brightness levels, according to an announcement by DuPont. Though that’s still a lot less than the 50 000 to 80 000 hours of an LCD, it’s enough to allow an OLED TV to run about 18 hours a day for at least seven years.

Still, these large-screen OLEDs aren’t going to be cheap. LG and Samsung, the other large Korean consumer electronics manufacturer, were to begin shipping 55‑inch OLED televisions by the end of 2012. At press time, pricing had not been announced but was widely expected to be in the $10 000 to $13 000 range. So these early models won’t exactly fly off the shelves. But, says O’Donovan, “I’m convinced both Samsung and LG will continue with OLED production even if it is a slow niche market for three to four years, because producing these will enable them to increase yields and put them several generations ahead of anybody else.”

At least two other companies are scrambling to catch up. In 2012, Japanese companies Sony and Panasonic, usually bitter competitors, announced that they would pool their OLED technology to help them both start mass-producing 55-inch displays this year.

The companies are tackling the OLED in different ways. Samsung is using three OLEDs—one red, one green, one blue—for each pixel; LG is using white OLEDs throughout, creating subpixels with colored and white filters. O’Donovan says he thinks, at least in the short term, that LG’s white OLED approach “will be better for yields and will create a more uniform color for the whole panel.” He argues that although researchers have extended the lifetime of blue OLEDs to about 20 000 hours, white OLEDs eliminate the problem of fading blues altogether.

So this year you’ll be seeing OLEDs in the stores and in the homes of early adopters—and that gorgeous, large, flat LCD TV you bought last January won’t look state of the art anymore.